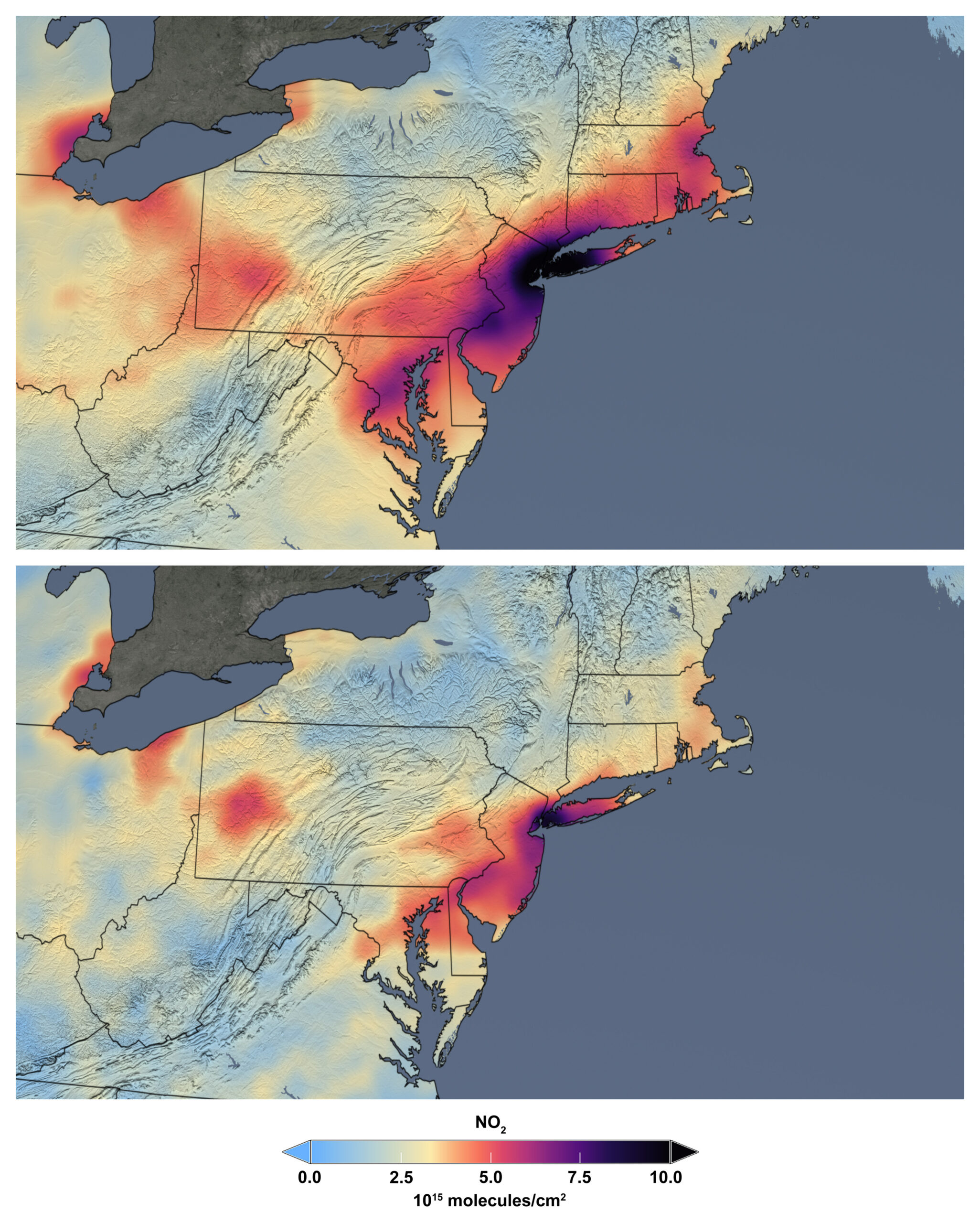

As the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the world economy to a standstill, greenhouse gas emissions have plummeted, seeing the biggest drop since World War II and producing striking satellite images of improved air quality in heavily polluted areas like Wuhan, China and Southern California.

Greenhouse gas emissions mirroring the world economy is nothing new — the last time emissions noticeably fell was in the wake of the Great Recession in 2008.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But will the 6 percent dip 2020 is projected to see make a difference in the fight against climate change?

Ankur Desai, University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of atmospheric sciences, said while the emission declines may be dramatic, they won’t have an immediate impact on the climate or the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

“For emissions reductions to meet climate change targets that limit the harmful effects of climate change, that would require a drop of this magnitude to occur every year for the next several decades,” Desai said. “Of course, we don’t wish this level of economic calamity on anybody, and that’s not how the future transition for emissions reduction would happen.”

That doesn’t mean there isn’t value, or lessons to learn from this experience, he said.

“That’s a pretty tall order,” Desai said. “But it does talk both about the enormity of the challenge and also how humans can actually change the environment, that we can change our activities as needed.”

Each year about 40 billion to 45 billion tons of carbon dioxide are emitted into the atmosphere from fossil fuels, he said. That increases the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere — which can take centuries to be removed.

For the last few decades, that concentration has been increasing every year as the economy has grown and as the world has been using more fossil fuels, Desai said.

Yet pre-coronavirus outbreak, a slow shift has been taking shape.

“The rate of economic growth is growing faster than the rate of fossil fuel emissions,” he said. “What that means is that we’re seeing the ability to grow human activity in the economy without necessarily always using the same amount of fossil fuel.”

That’s a good thing, Desai said, because it means we’re using more renewables and becoming more efficient.

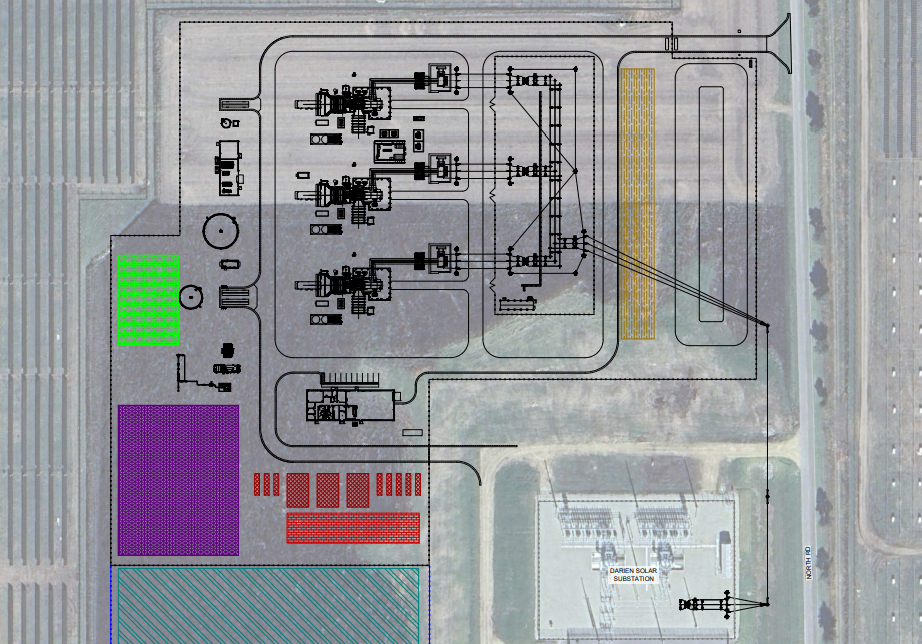

At the same time these changes are happening, the renewable energy industry is coming off of record years in growth.

In 2019, solar represented 40 percent of all new electricity generation capacity in the United States, the fastest growing sector, and solar installers and wind technicians were the two fastest growing jobs in the country.

Like nearly every industry during the COVID-19 outbreak, there’s a lot of uncertainty about what the pandemic will mean for the renewable energy field — layoffs, supply chain disruptions and concerns about future projects have all hit the industry.

In Wisconsin, clean energy supports more than 76,000 jobs, the majority of which are in energy efficiency. Nationally, estimates for job losses in the solar industry are as high as half of the industry.

“We’re still figuring out how this will affect the whole industry, and there’s a number of different parts of the industry that it will impact,” said Heather Allen, interim executive director of RENEW Wisconsin, a nonprofit, renewable energy advocacy group.

So far, the renewable energy industry has largely been left out of federal relief from the stimulus packages — though some small-scale residential and commercial developers have been able to apply for small business loans.

Another big concern in the industry is the phasing out of federal subsidies that came from Obama’s 2009 stimulus bill.

Slowdowns caused by COVID-19 layoffs and supply chain disruptions could cause projects to miss the deadlines they need to receive the full tax credit, said Sarah Johnston, assistant professor at UW-Madison, whose research focuses on the economics of the renewable energy industry.

“For example, wind projects that were started in 2016, they had to be completed by 2020 to get the whole subsidy … instead of getting the full subsidy, they’ll get 80 percent of the subsidy, or something like that,” she said.

A policy to extend those deadlines was cut from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, though both Johnston and Allen are optimistic about the next stimulus bill.

Then there’s the future projects.

Despite initial concerns, projects with signed contracts appear to be moving forward with little disruption, but those in the industry are concerned that future projects will dry up before they begin.

“The outlook for projects that were planned, but haven’t made it to where all the contracts were signed, is quite dismal right now,” Johnston said.

As far as long-term impacts on the industry, Allen said the jury is still out. Things could slow down, but at this point that hasn’t happened in Wisconsin.

In some cases, like residential solar projects, there’s been a slight increase, which Allen suspects may have something to do with people thinking about resiliency and surviving a crisis.

“But it’s tricky,” she said. “I think the truth is we don’t know exactly how this will play out.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.