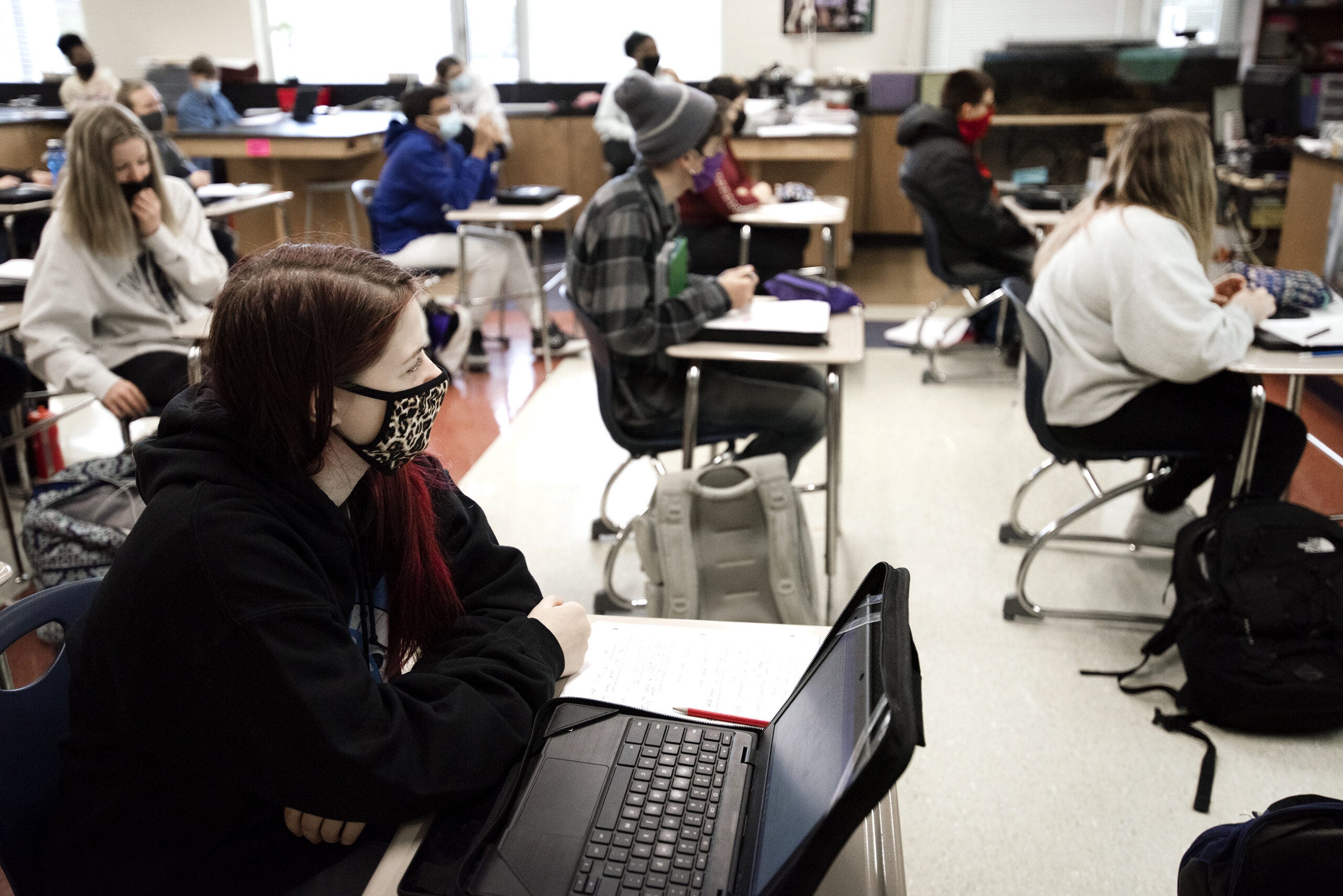

In a typical year, schools teem with everything from stuffy noses and sore throats to more severe influenza strains and strep throat. With kids crowded together, sharing often poorly-ventilated classrooms for hours at a time as they cough and sneeze, it can seem inevitable that schools are a major spreader of seasonal bugs that circulate through a community.

Over the past year, though, the precautionary measures to stop the spread of COVID-19 in schools have brought the spread of other illnesses almost to a standstill.

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services has reported zero deaths from the seasonal flu among kids since October, and a massive reduction in flu cases. University of Wisconsin-Madison pediatric infectious disease specialist Dr. Greg Demuri said respiratory syncytial virus, a common illness in infants and toddlers that’s one of the leading causes of hospitalizations in children, has all but disappeared this year.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“There has been a real ecological shift over the past year of the pandemic,” Demuri said.

However, while the sharp drop in usual illnesses can likely be attributed to COVID-19 containment strategies, Demuri said it’s hard to tell which ones exactly have made the most difference — as well as what’s feasible to expect kids to keep doing once the threat of COVID-19 decreases enough to safely relax current restrictions.

“Is it masking, is it the social distancing, is it the fact that kids are just not interacting with the other kids?” he said.

Brea Sanders, a nurse in the Whitnall School District, said she’s also seen fewer illnesses spreading in her district — which has been teaching students in person — this year.

“We’ve seen definitely a decrease in the incidences of colds and flus,” she said. “Viral illnesses that we would typically see around this time definitely have not been as prevalent as in previous years.”

She attributes the decrease to better education and practices around washing and sanitizing hands, as well as disinfecting surfaces and social distancing. Masks, she said, have been a big help, but mask-wearing might not last past the pandemic.

“The mask-wearing, it definitely would be a harder sell, I think, for some people,” she said. “But that’s been a big piece of preventing the respiratory droplets from spreading around when people are sick.”

Sanders said she could see some families using masks periodically if they’re worried, for example, that what looks like an allergy flare-up could instead be a virus, and want to be more cautious.

Although kids have been shown to be at lower risk of contracting COVID-19, they’re the main drivers of the more typical seasonal flu, said Dr. Laura Cassidy, an epidemiologist at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

“Their activities, being in schools and day cares, is what really drives transmission,” she said.

With more kids staying home, she said, it makes sense that transmission is down. But even as schools bring all their students back into classrooms, and more families put their kids back into child care programs, the pandemic has driven some structural and social changes that could lower the spread of other illnesses — in particular, upgrades to ventilation systems in schools and businesses. But she said there’s also a shift in mindset that comes from a full year of people reorienting their lives around a deadly pandemic.

“This generation of young children has grown up being more aware of the spread of disease, and learning more about it — good sanitation, good respiratory hygiene, use tissues, sneeze into your elbow, wash your hands,” she said.

That awareness extends to symptoms of illness, as well. Families that might have previously sent kids to school with a cough or other symptoms short of a fever or vomiting have, in some cases, been more aware of those symptoms this year, and more inclined to keep kids at home.

“I think people have pulled back on that, and that has probably greatly contributed to the drop in a lot of infectious diseases we see in children,” said Demuri.

He noted, however, that parents and guardians need flexibility from their own workplaces to make that feasible — being allowed to work from home, for example, or having a more generous sick leave policy.

Both Demuri and Cassidy said schools should continue to focus on ventilation and airflow. Demuri said schools can also reconsider the flow of students, structuring the school day to prevent overly crowded hallways.

The novelty of COVID-19 has made it easier for schools and families to adapt to more extreme measures, from staying home to wearing masks, but Demuri said the diseases that pop up annually pose a threat as well — just not one that gets as much attention.

“Those types of deaths are happening from other viruses every year. I’ve seen deaths from flu in children in my career, and it’s devastating,” he said. “I think we could do a better job of explaining the benefits (of mitigating these other diseases).”

At the same time, though, he’s mindful of the trade-offs that come with some of the more disruptive disease mitigation strategies, like keeping children home from school, or limiting time in-person with their friends. He said American Family Children’s Hospital, where he works, has seen a substantial increase in visits for mental health reasons like anxiety, depression and eating disorders. Effective long-term strategies have to balance kids’ mental health needs against the need to limit disease spread.

Demuri, Sanders and Cassidy laid out some less-disruptive steps that families and schools can continue to take to keep the spread of other diseases low:

- Washing or sanitizing hands, especially after coughing, sneezing or blowing a nose.

- Sanitizing desks and other high-touch surfaces regularly.

- Keeping a distance from others when sick.

- Being more mindful of potential disease symptoms and keeping students home when feasible — not only to limit the risk to others, but to help kids recover faster.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.