More than half of the world’s supply of cranberries comes from Wisconsin. One of only three native crops to be commercially cultivated in the United States, cranberries have adapted alongside Wisconsin’s climate. But warming winters and increasing extreme weather events are leaving the cold-hardy crop vulnerable. In this series, WPR is exploring how the state can adapt to and mitigate the affect climate change is having on some of Wisconsin’s most iconic foods.

There are cranberry vines in Wisconsin that have been producing the vibrant, tart fruit for more than 100 years.

A perennial, native plant to Wisconsin, cranberries are well adapted to the state’s climate and landscapes. And the cranberry growers here have gotten very good at engineering production to make Wisconsin the No. 1 producer of cranberries in the world.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Bringing in nearly $1 billion in annual revenue to Wisconsin, according to the state Cranberry Growers Association, Wisconsin’s cranberry industry makes an enormous mark on the state’s economy. About 250 farms produce more than half the world’s supply on 21,000 acres, the majority running along Highway 173 between Tomah and Wisconsin Rapids in central Wisconsin.

But changing weather patterns driven by climate change are testing cranberry farmers, and posing challenges to a well-established industry that’s unable to switch gears quickly.

Warming Winters, Wet Summers Challenge Fruit Quality

Able to withstand Wisconsin’s often low temperatures, cranberries are a hardy crop that have thrived alongside the region’s ample supply of water, cold winters and sandy, acidic soil.

But experts are worried about the long-term effects of climate change on the fruit.

Intense rainfall events can increase the fruit’s odds of experiencing rot; an extreme hailstorm can take out an entire crop; an early thaw can trick a bud into flowering too soon; and warming winters can increase pest pressure.

Farmers like Nicole Hansen, of Cranberry Creek Cranberries in Necedah, have spent decades managing cranberry beds. She says weather has always been unpredictable.

“From my standpoint … we’re going to analyze things, we’re going to try to be proactive,” she said. “But that’s agriculture and that’s our job … we work right along with Mother Nature and watch what happens from a weather standpoint.”

Graph courtesy of the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts

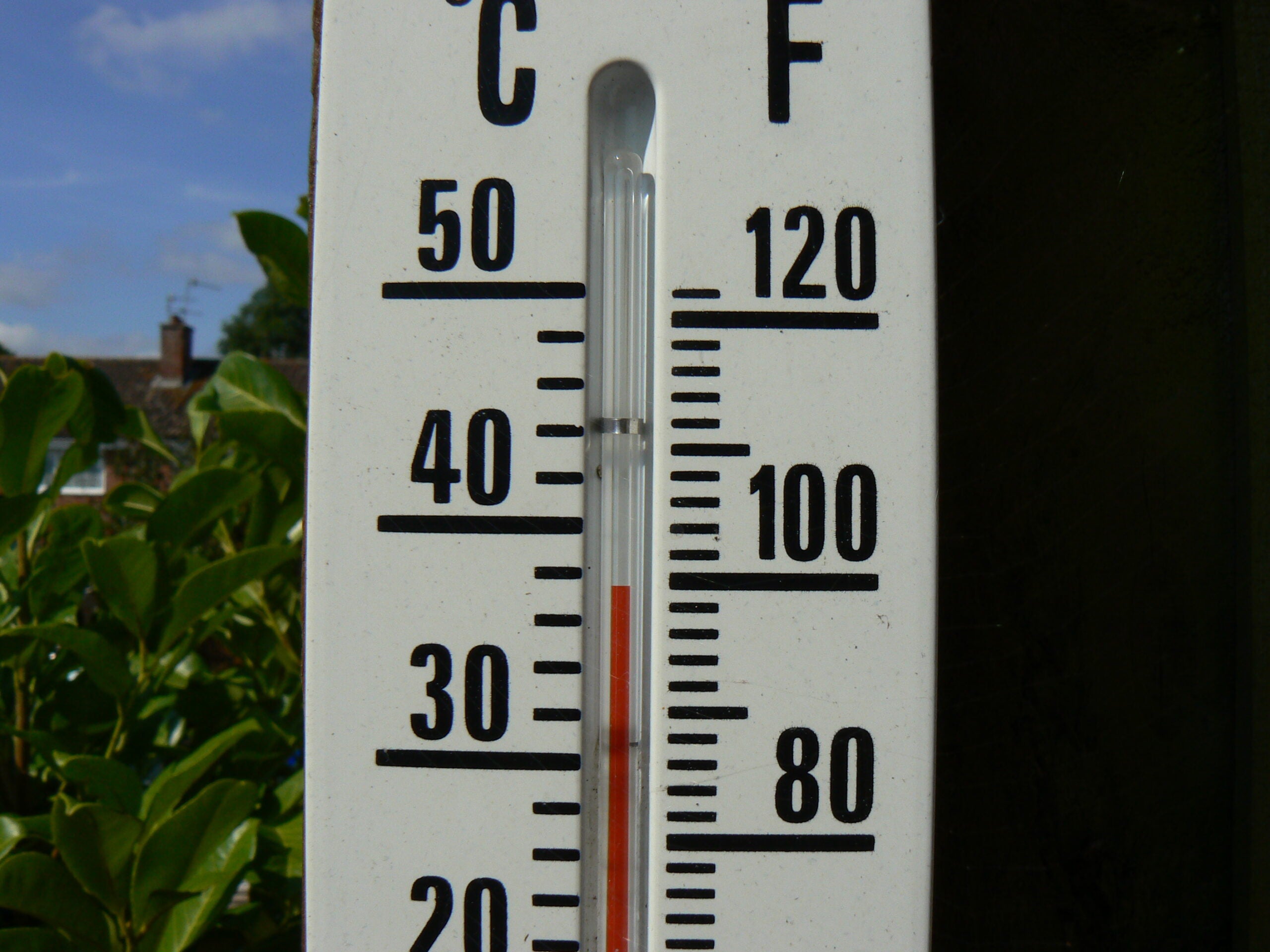

Wisconsin has already warmed by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit, but winter has experienced the greatest increase in temperature. By mid-century, Wisconsin winters are expected to be 5 to 11 degrees warmer than they were in 1980, according to the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts.

January 2020 was Earth’s warmest January on record, and four of the warmest Januaries have occurred since 2016.

Cranberries need both ice cover protection and dormant chill hours to produce fruit in the summer. Repeated freeze-thaw disruptions, caused by erratic winter temperatures, and events like 2019’s polar vortex are asking a lot of the plant.

“When you change the conditions and those winters become more extreme, the plant is disoriented,” said Amaya Atucha, fruit crop specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“Going from really, really cold to sometimes getting warm in the winter … they have to adapt to both of them,” she continued.

For cranberries, the risk is greater.

Unlike with annual plants that start fresh every growing season, cranberry growers have to keep the plant healthy year after year — as a perennial plant, it takes three to four years before a new plant will produce fruit.

Cranberries have built in resilience as a native plant, but those strengths can also be limitations amid a changing climate, said Jed Colquhoun, professor in the UW-Madison Department of Horticulture, who specializes in commercial fruit and vegetable production.

“That variety was improved and selected for, let’s say, 100 years ago,” he said. “That doesn’t mean that’s necessarily right for a changing climate. So, can it tolerate more stress? Maybe … but the risk is also much higher because it’s so expensive to change.”

Atucha said at this point, issues related to climate change are mostly impacting the fruit quality and what it takes to have a good production year.

Fruit quality and moisture levels are deeply connected. And as a crop highly dependent on exterior quality, too much water isn’t good for any aspect of cranberry growing.

Graph courtesy of Dan Vimont, director of the Center for Climatic Research

Warm air holds more moisture, which leads to higher rainfall events and greater humidity. Fruit rot, insect pressure and competition from other plants like moss are heightened by recent record-breaking wet years.

“It’s wet all the time, we don’t get that drying cycle,” Colquhoun said. “So not only do cranberries not grow well, but some of the pests that will reduce cranberry vine growth and yield are more prolific in wet environments.”

While the classic Wisconsin cranberry image features the tiny red fruit floating in water — perhaps contrary to popular belief — cranberries aren’t actually grown in water. Farmers flood the beds to ease harvest and the cranberries float because they contain a tiny pocket of air.

Cranberry growers protect the fruit buds in the winter by covering the beds with a thick layer of ice, which acts as insulation for the plant.

“We’re like ice engineers,” Hansen said. “We’re probably the only people in Wisconsin who like it to get below zero.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.