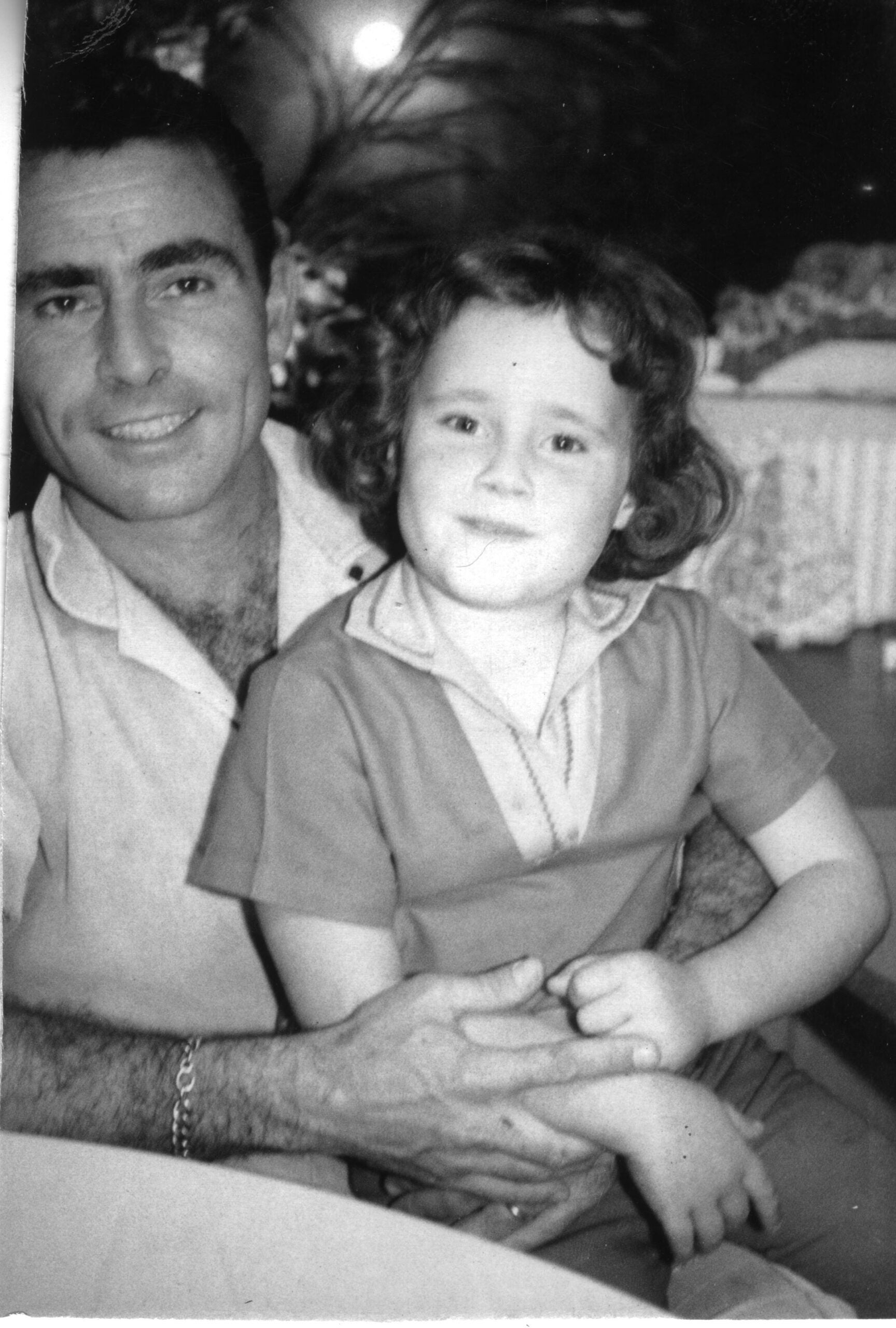

Rod Serling, best known as the creator of “The Twilight Zone” television series, died of a heart attack at the age of 50 when his daughter Anne Serling was just 20 years old.

WPR’s “BETA” talked with Serling about her life with her dad and why she felt it essential to write about her father in her memoir, “As I Knew Him: My Dad Rod Serling.”

“The last time I saw my dad was 49 years ago,” she told “BETA.” “It was the night before his surgery. And he told me that he loved me.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“He was told that when he came out of surgery, he might not recognize us. He said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll know who you are.’”

The following has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: Anne, why did you decide to write this memoir?

Anne Serling: It was to navigate my grief. I had started another book called “In His Absence” years before, and I had yet to work out that whole minefield of grief. So, I never finished the book.

Then I started “As I Knew Him,” partly because I find writing cathartic, like my father did.

It was interesting because before I finished the book, I gave a reading at the Paley Center, and a woman came up to me and said that her father was dying. After she heard me read, she knew she’d be OK. It was such an unexpected gift that something I had said resonated. I’d helped her and couldn’t speak; I just hugged her.

The second reason I wrote the book is that I wanted to learn more about my dad’s personal and professional life. The third reason is that I wanted to dispel rumors that my father was a dark and tortured soul, because he was anything but. My dad was funny and silly. He loved ‘The Flintstones” and did the best gorilla imitation you could imagine.

DG: Your dad served in the Philippines and received a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart. What impact did his military service have on him?

AS: The war significantly impacted him, as it does on anyone we throw into these wars. He was very traumatized, and I vividly remember him having nightmares.

In the morning, I would ask him what happened, and he said he had dreamt that the enemy was coming at him. He said he initially wanted to major in physical education because he liked working with kids. He’d worked at a summer camp for kids with rheumatic fever, which he said helped pull him out of his despair.

So, he was going to go to Antioch and major in phys ed, but then changed it to language and literature because, as he said, he realized he needed to get it out of his gut. He needed to find a way to deal with his trauma.

DG: Your dad wrote a “Twilight Zone” episode called “The Big Tall Wish” for the show’s first season. Can you tell us about this episode?

AS: I wasn’t aware of it when he wrote it. I was 4 years old, but I believe Marc Zicree summed it up best. He said the casting of African Americans in a dramatic show, not dealing with racial issues practically, was practically unheard of and deliberate on my dad’s part.

It’s a lovely episode about the relationship between a boxer and this little boy, and the little boy urges the fighter to believe in magic. It’s a very tender, wonderful story.

DG: How is your father able to separate work from family? Because he wrote so many episodes, how could he make time for you and the rest of his family?

AS: He had written 92 of the 156 “Twilight Zone” episodes, and I read an article that said he worked 12 hours a day, but I never had the sense that he wasn’t available daily. When I came home from school when I was younger, he and I would play basketball.

There were times when I knew my father wasn’t present and was sort of writing in his head because he’d get this stare on his face, and I knew I’d lost him for a few minutes.

DG: What was it like to see your dad on television?

AS: I didn’t watch any of “The Twilight Zone” episodes while my dad was alive, but we did watch the Christmas episode, “Night of the Meek,” every Christmas. He had an office in the backyard, and we’d go out and lie on the floor and watch it, and it was thrilling. My dad was on the soundstage with what looked like snow falling on his jacket. It was exciting.

DG: What is your all-time favorite “Twilight Zone” episode?

AS: One of my favorites — one that I had not watched while my father was alive — was “In Praise of Pip.” As I watched it, I realized that my dad used dialogue from a routine he and I used to do: “Who’s your best buddy?” “You are.” So, it was quite a poignant moment because I rediscovered my father in “The Twilight Zone.”

DG: It’s been nearly 50 years since your father passed. Why are we still discussing your dad’s writing and “The Twilight Zone”?

AS: I think we’re still talking about it because my dad dealt with the human condition and moral issues and things that we’re all sadly still dealing with today. My dad was very vocally disheartened and enraged about racism, mob mentality, marginalizing and isolation. I’ve said this before, and I’m certainly not unique in saying this, but times change, and people don’t.

DG: How did writing your memoir affect your feelings about the passing of your dad?

AS: It was, in a sense, cathartic, of course. It was a joy to spend every day with him, thinking about him, writing about him, researching, hearing what people had said about him after the publication of my memoir, and hearing from people who wrote me the most unexpected, lovely things about my dad’s influence on their lives.

Some had said they became writers because of my father. Most interesting, some of these people came from rather tumultuous childhoods. They said they thought of my dad as their father.

I heard from a guy who had been a conscientious objector, who had hidden out in a church basement and had said that my father saved his life — hearing my father’s voice say not to give up hope that no matter what the future brings, we’re going to be OK.