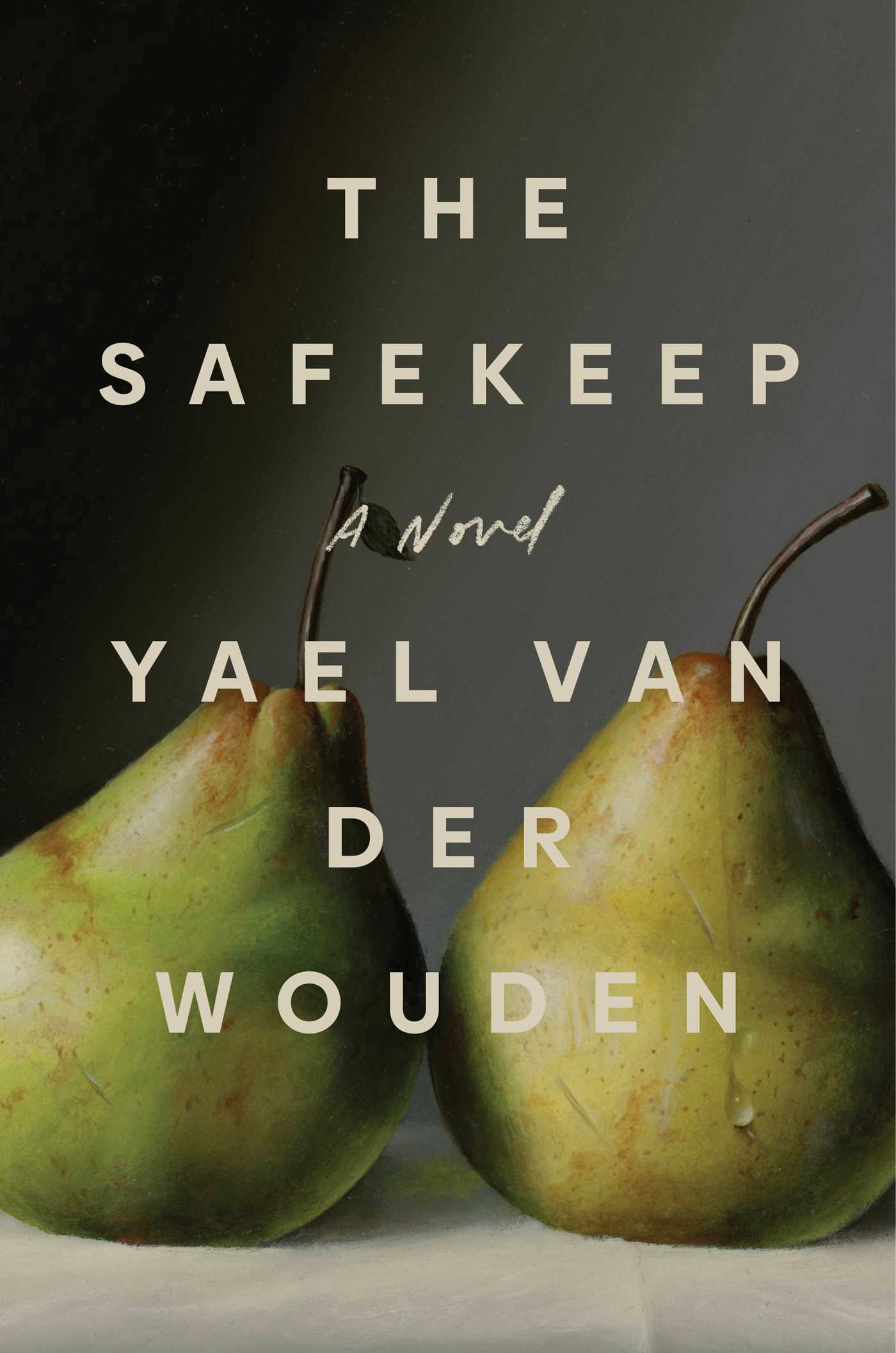

At first glance, Yael van der Wouden’s stunning and critically acclaimed debut novel, “The Safekeep,” appears to be about displacement. She notes that nearly every character in the novel faces a different form of displacement.

However, dig a bit deeper and van der Wouden believes that — as cliché as it may sound — the novel is about hope.

Set in the post-war Netherlands of 1961, the story studies the rigid and restrained Isabel as she quietly and meticulously cares for her family home. Both of her brothers left her to deal with their mother and she inherited the home, in practice, when she died, although her eldest brother, Louis, legally holds the title.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Isabel’s life is upended when Louis is called away for work, but wants his new girlfriend, Eva, to stay at their home.

As Eva’s stay increases, Isabel finds a lot of the family heirlooms begin to go missing and the two of them must confront the truth about themselves, their shared home and a world still reeling from the war.

“The Safekeep” ends up being about what it means to build a home and the true cost of redemption.

van der Wouden joined WPR’s “BETA” host Doug Gordon for a conversation about her novel that was shortlisted for the Booker Prize.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Doug Gordon: How did you envision Isabel when you were developing her as a character?

Yael van der Wouden: What I really wanted to do with this novel is I wanted to start with a character that was locked inside of herself. And also, I wanted it to be a character that you start reading it and you just dislike her immediately. You do not want to be with this woman.

I think, for me, one of the most satisfying things about novels and stories can be when you start out thinking a certain way about a character and by the end of it, your experience of that person has been entirely changed.

In novels, when that happens, when you start out with a character that is befuddling and annoying and then through seeing them as a complete and full person, you come to love them.

I think that is such a rewarding experience and that is also, in turn, what happens to Isabel. She meets somebody that she dislikes and then in getting to know that person, she comes to love her.

And so, we’re experiencing with Isabel what Isabel is experiencing towards Eva. And that’s what I was hoping to do. To create a character that is locked within herself. And we do not like her. And then by the end of it, she’s torn apart. And we’re also changed in our reading experience.

DG: Isabel’s life changes dramatically when her brother, Louis, brings his new girlfriend, Eva, over to Isabel’s home. What happens next?

YvdW: Isabel, for the first time in her life, has to share her space. She doesn’t have many friends, or any friends, really. She distrusts notions of friendship. She sees it as a kind of theater that she doesn’t believe in. She thinks there’s something fake and unreal about friendship.

She has to play host to this person that she dislikes very, very much. And so, she has to confront a lot of things about herself.

And then, of course, there’s the parallel storyline where things are disappearing from the house. And Isabel was so attuned to every single item.

And so, while she’s obsessed with Eva, she’s also becoming increasingly obsessed with keeping the house in order and figuring out who is taking her things.

DG: “The Safekeep” has an epistolary section and paired with the Amsterdam and World War II setting, there seem to be some obvious parallels to Anne Frank. Was “The Diary of a Young Girl” an inspiration at all?

YvdW: I’ve never read her diary, is the thing. At first, it was a bit of resistance on my end, especially in the Netherlands. I didn’t want to participate in an act that would reduce me to some kind of stereotype.

Then as I got older, I became more and more uncomfortable by the role that her diary takes up in the Dutch public, because it’s such a such a central text to Dutch identity. It’s co-opted in a very interesting way where it’s paraded about as a text that comes from the culture and belongs to the Dutch culture.

The fact that the Frank family met the fate they met is because of Dutch collaboration, because of Dutch betrayal. And so that narrative is always sold as a narrative of pride rather than — I wouldn’t want to use the word guilt — but like there’s an element of complicity that I’m always missing in Dutch narratives around Frank.

So, I would say that the diary itself couldn’t have inspired me because I haven’t read it. But it did inspire me in the sense that conversations around the diary have irked me enough to write that epistolary chapter.

DG: How does it feel to become the first Dutch author on the Booker Prize list?

YvdW: I don’t know if I’ve had the time to really sit down and fully process it. It feels a little bit like cheating.

Doug: Why does it feel a bit like cheating?

YvdW: Because there’s, of course, also the International Booker where over the last several years, we’ve had several Dutch titles, translations of Dutch titles that have been nominated for those.

But it is both incredibly flattering, humbling and terrifying as well.

I think that the Dutch response to this has also been mixed. I think some people are very excited about it. Some people disagree with the nomination.

I think it’s because I wrote it in English, and it feels a little bit like I’ve taken a Dutch story and wrote it for others and then sort of pass it on to those who are on the outside rather than keep the story within. And I think that’s creating a bit of friction. They’re absolutely welcome to feel what they want to feel about the story.