A 19th century powder horn that belonged to a Stockbridge-Munsee leader has been returned to the tribe, which will display it at its museum in Shawano.

John W. Quinney was a sachem of the tribe in the 1850s. That designation came after decades of leadership that included lobbying and addresses to Congress, securing land in Wisconsin for the tribe and ensuring that Stockbridge-Munsee people would be recognized by the U.S. government as a tribal nation.

The carved horn held gunpowder, and still smells faintly of it, Emily Rock of the Oshkosh Public Museum said in an online presentation about the object. Its stopper has a stylized carving of an animal’s face, and the initials “JWQ” are carved on its side.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

[[{“fid”:”1389986″,”view_mode”:”embed_portrait”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EJohn%20W.%20Quinney.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EImage%20courtesy%20of%20the%20Smithsonian%20Institution%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”John W. Quinney”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”John W. Quinney”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”embed_portrait”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EJohn%20W.%20Quinney.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EImage%20courtesy%20of%20the%20Smithsonian%20Institution%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”John W. Quinney”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”John W. Quinney”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”John W. Quinney”,”title”:”John W. Quinney”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-portrait media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

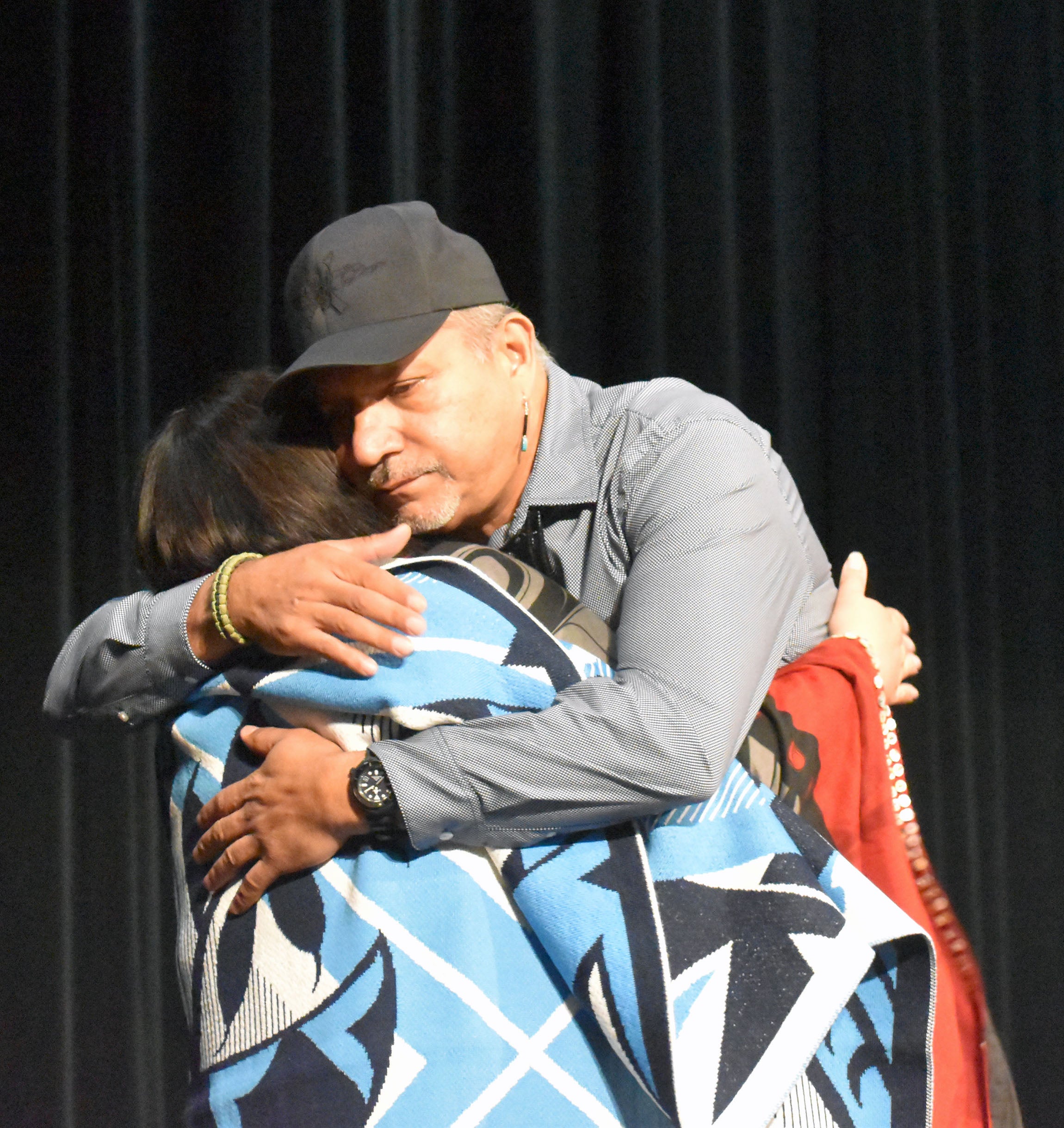

It was held by the museum from 1934, when a collector loaned the item to them, until November when the museum completed the legal process of repatriating it to the Stockbridge-Munsee. In a ceremony at the Arvid E. Miller Stockbridge Munsee Historical Library Museum, representatives from the Oshkosh Public Museum formally gave back the item.

The repatriation is a marker of the “immense value and impact it would have to our people and our cultural identity,” said Bonney Hartley, the tribe’s historic preservation manager. And it is a sign of changing attitudes, she said, that the relationship between the tribe and the Oshkosh Public Museum was not antagonistic.

The museum had denied a repatriation request in 2002. But when Hartley and other tribal members approached them recently about the claim, the museum had different leaders, and the process went very differently. The tribe prepared detailed claims describing the object’s cultural importance and also the Arvid E. Miller museum’s ability to preserve it and display it. The Oshkosh museum’s board of directors this year voted unanimously to return the horn.

That’s important, Hartley said, because it can set a precedent for repatriating other objects to their Native American homes. That includes other items once owned by Quinney.

“We have some of his items at home, and it would make more sense to reunite everything that’s out there in one place,” Hartley said.

Not all of the cases Hartley works on go as smoothly. Under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, her work for the tribe also involves identifying human remains that have been sold by collectors or displayed in museums, so that they can be returned for burial. It’s painstaking, sometimes emotionally trying work. And while the law permits tribes to reclaim human remains and sacred objects, some owners contest those claims, which can lead to protracted legal battles.

It was under the same law that Quinney’s powder horn was designated an “object of cultural patrimony.” In other words, its importance to a museum is not as an example of a tool of daily life in the 19th century, but rather the fact that it belonged to one of the tribe’s modern founding fathers. There are other objects of Quinney’s displayed at other museums, Hartley said, for which the same argument does apply. She said they rightfully belong to the Stockbridge-Munsee. In the future, she hopes the Arvid E. Miller museum can loan them out to other museums for display for educational purposes.

“Hopefully one by one, we’ll get to return all of his belongings,” Hartley said. “There’s still quite a bit that out there. It’s all fragmented and will have less meaning on its own in individual places, we think, than if it’s all together.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.