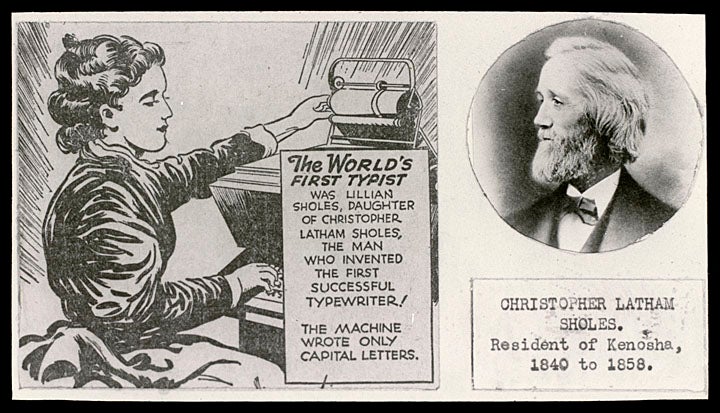

Milwaukee’s Christopher Latham Sholes patented the first practical typewriter this week in 1868. The machine revolutionized communication and opened doors for women, like Sholes’ daughter Lillian, billed here in the above image as the “world’s first typist.” (That’s Sholes to the right.)

There was no single moment of discovery for the typewriter but rather a variety of models as inventors struggled to craft a usable design. Sholes read about typewriters in “Scientific American” and decided to come up with his own model. A mechanical engineer by training (though he worked as an editor, postmaster, commissioner of public works, and collector of customs), Sholes spent hours at Kleinsteuber’s Machine Shop in Milwaukee tinkering with his friends Carlos Glidden, Samuel Soule and Matthias Schwalbach. They first mounted an old telegraph machine on a base and made an image by tapping carbon and paper against a glass plate. Sholes then proceeded to construct a machine that would produce the entire alphabet.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Part of the challenge in designing the machine was placing the letters so that the key arms didn’t jam together. Sholes came up with the so-called QWERTY keyboard, still widely used today, after assigning his son-in-law to identify the most common two-letter sequences in the English language. By separating these letters on the keyboard, Sholes kept the arms from sticking together. It wasn’t the most efficient or intuitive design but people got used to it. Sholes’ design was patented on Aug. 27, 1868. This first machine typed in all capitals and had a lid for the keyboard.

Investor James Densmore helped to fund the continued development of the typewriter over the next several years. His marketing assistance helped bring the machine to E. Remington and Sons, which began manufacturing the typewriter along with its firearms, sewing machines, and farm tools, in 1874.

The typewriter wasn’t an immediate success. Who wanted a mechanical writing device? Many Americans distrusted writing that didn’t come from a human hand. But as industrialization made work more specialized and businesses bigger, typewriters gained acceptance for typed correspondence and accounting. It also opened doors for women to be trained as typists and to find office careers.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.