The stardust looks surprisingly ordinary. No sparkle, no gleam — just a fine, dark brown powder, suspended in a hand-blown hourglass. The shock comes when you realize what you’re looking at: remnants of a meteorite that’s not just older than Earth, but older than the solar system itself.

Katie Paterson, of Glasgow, Scotland, describes her 2022 art piece “The Moment” as an experience of deep time.

“I knew that I wanted to find the oldest material on earth, and I wanted to make an hourglass with it,” she said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Over the past decade, the artist has built an international reputation for work that spans the most distant edges of time. Her materials are melting glaciers, dead stars and fossils of the first trees and insects.

Paterson talked with Anne Strainchamps for the “Deep Time” series on “To The Best Of Our Knowledge.”

Paterson said her cosmic hourglass was first exhibited in Durham Cathedral, England, which she thought was perfect. The hourglass runs for 15 minutes —about the length of a meditation session.

“It was a lovely thing to sit and just watch this ancient dust drip and flow,” she said. “It slows you down, watching time and feeling time.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Anne Strainchamps: I find it almost impossible to describe the feeling your work evokes. The way the finite and the infinite combine — sometimes I can feel my mind kind of stutter and wobble trying to take it in. I think that’s because your primary material is deep time, which is so hard for us to fathom. Why is deep time so important to you?

Katie Paterson: It sort of crept up on me and then over the years became more and more fundamental to the artwork that I make. Probably 99-point-something percent of my life, I’m not living in a deep time haze. I wish I was, but there are these little moments when you kind of grasp, even for a microsecond, the expansiveness of where we live and how we relate to everything else that’s ever been, and I just love that.

People often describe deep space and time — which are quite complex subjects — as intimidating, or too big or scary, even. But I’ve never had that feeling. For me, deep time is really beautiful.

AS: How far back can you trace your fascination with time? Does it go back to childhood?

KP: No. It’s funny — I wasn’t at all the kind of child that was into sciences or even space or being an astronaut or anything. I was certainly a bit of a geek. That hasn’t changed. But it was always art for me. Everything was art, art, art.

But then, I went to Iceland in between school courses one year. I was stationed way up north in a tiny hamlet and it was through direct experience of landscape, of light and the sky, that I had this feeling I had never had before, of: “My goodness, here we are on a planet that’s revolving.” So it took awhile for me to have that kind of experience, and it was as an adult, not as a child.

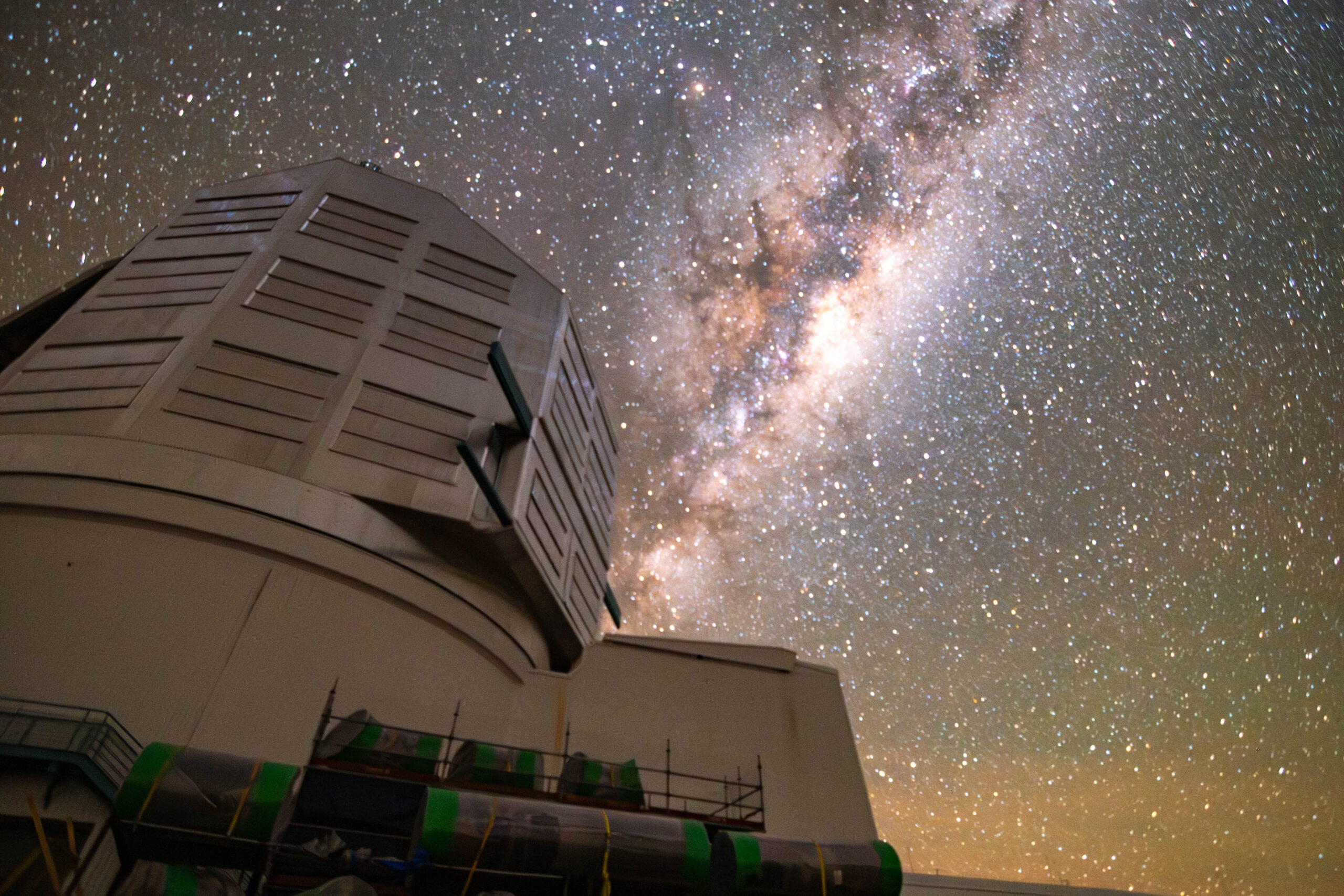

AS: Since we’re talking together, I was thinking we could construct an imaginary gallery and fill it with some of your work. The first piece I want to add to this gallery is “All the Dead Stars.”

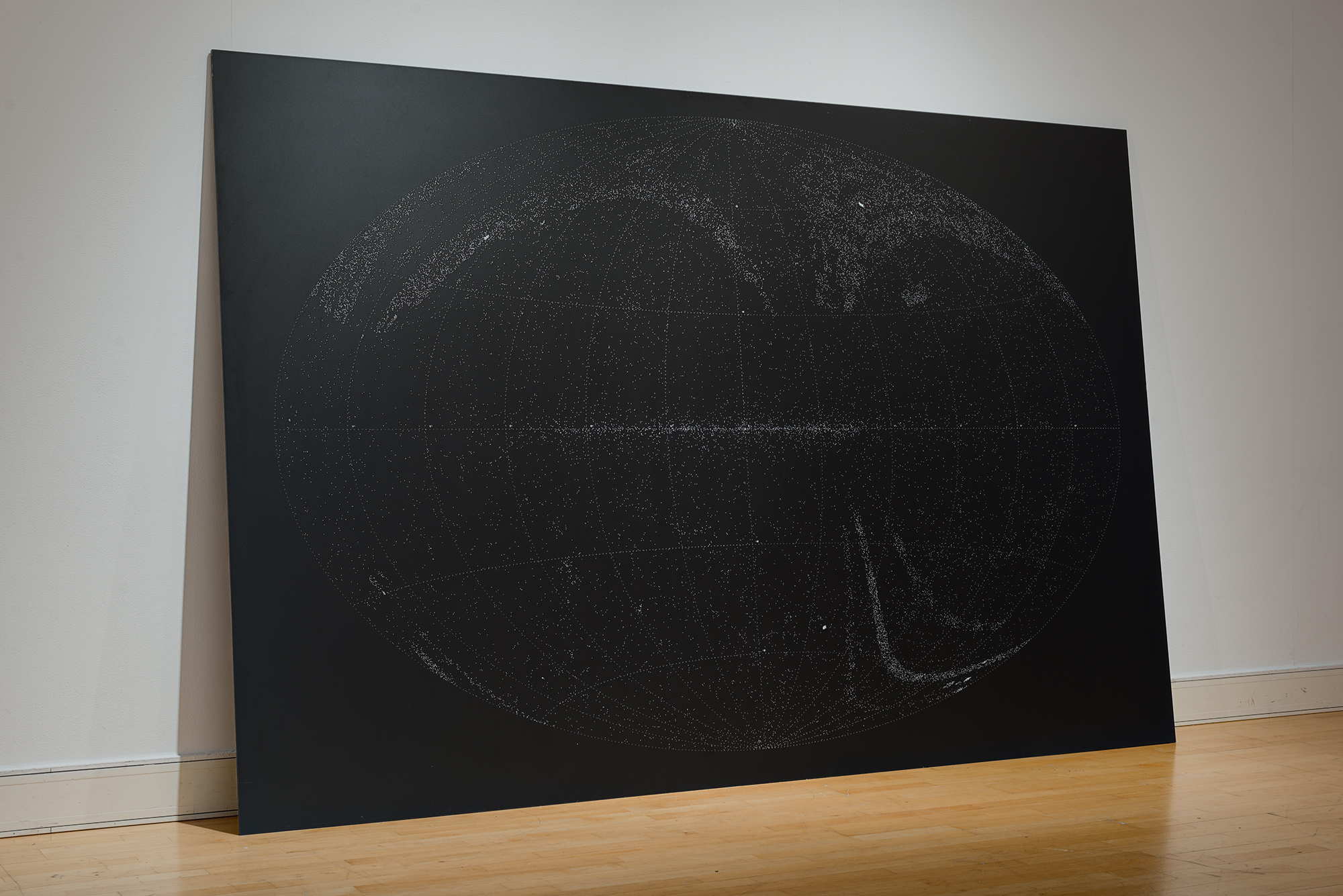

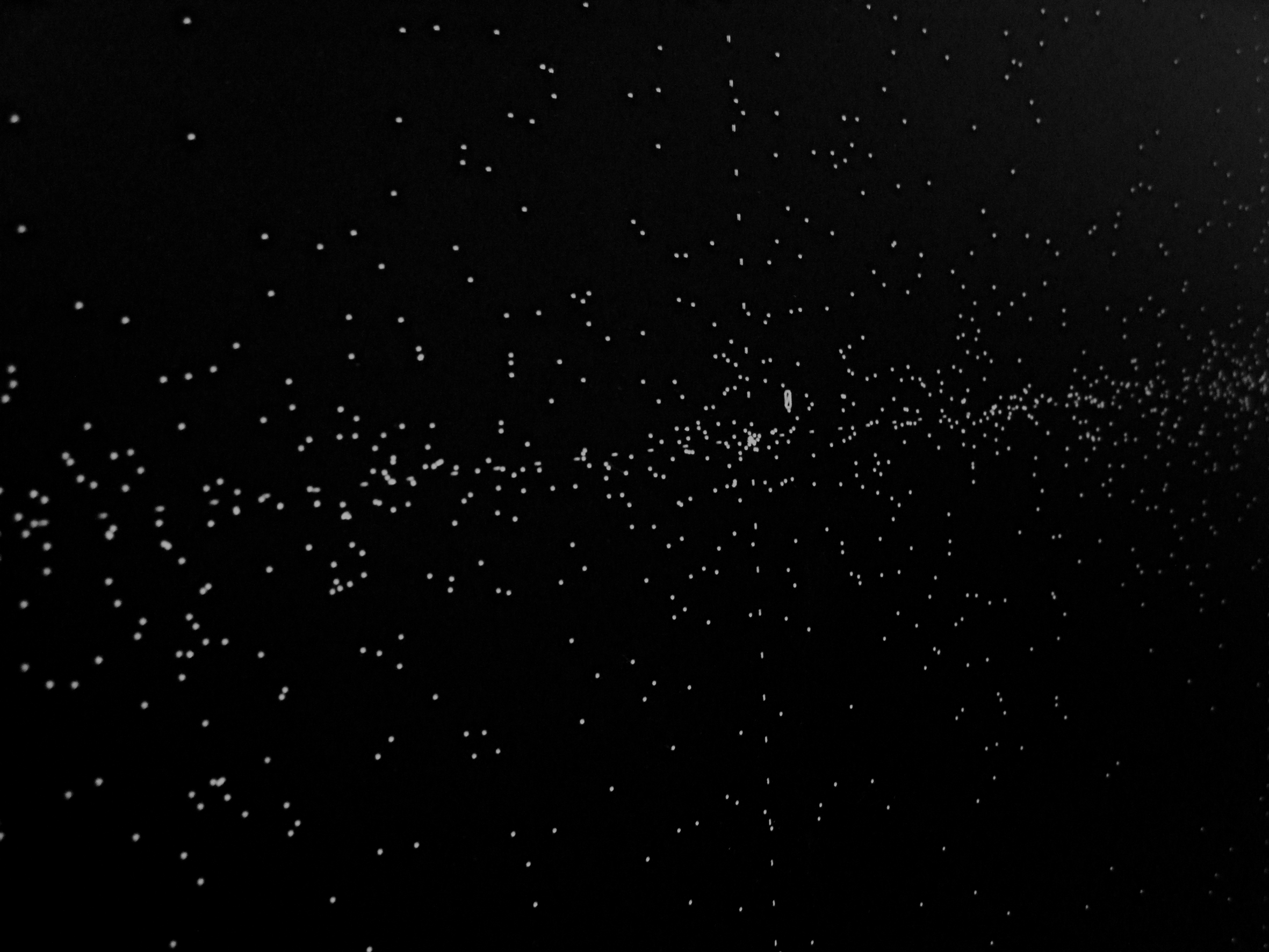

KP: “All the Dead Stars” is an artwork that came about through a residency I did at University College-London’s astrophysics department. That’s where I first learned about dying stars and knew that I wanted to make a map of them, of where they all were and how many there were. It ended up becoming this big, heavy, black anodized aluminum map. It’s quite sculptural. It sits tilted against a wall and we laser-etched what turned out to be 27,000 pinpoints of all the dead stars on it.

When you walk through the gallery, at first all you see is black, this big black space. And as you get closer and closer, a bit like a telescope, little dots of light start flickering and the silver starts shining through. Every one of these points refers to a place in the universe where a star has died — as a supernova type 1a, a stellar black hole, a gamma ray burst or something else.

What connected with me so much at the time was that if there hadn’t been stars dying, there would be no Earth. It’s through their remnants, through all the material they eject in these enormous explosions, that planets are formed. So we are the recycled remains of a star.

AS: Another work, and it kills me to not be able to viscerally experience this, is called “To Burn Forest Fire.” This is the one where you created incense sticks from forests?

KP: I’m so glad you brought that up because I loved working on it and I still love smelling it. The title, “To Burn Forest Fire,” is actually the Japanese word for incense. So we worked with Japanese perfumers and incense makers to recreate the scent of the first-ever forest on Earth, which we calculated at the time was in upstate New York, 385 million years ago. That’s when the first-ever trees made their way through the ground to become a forest. And what I wanted to do by creating the scent was to bring the smell of deep time into your body.

AS: What does it smell like?

KP: We were able to reconstruct the air and the atmosphere and the surroundings of these very fern-like trees, a little bit like club moss. It’s got a very fungal, humid smell. If it had a color, it would be earthy.

And then the second incense stick is what we’re calling “The Last Forest,” which we pray is not actually the last. It’s the Amazon rainforest, the most threatened forest on Earth and source of the most biodiversity on the planet. The scent notes included animals, fizzing alcoholic smells, guava plants — just the most amazing cocktail of things. And the perfumer did an amazing job because when we burned the first test, I walked in and said, “My God, it’s the Amazon!”

AS: Burning an incense stick is a kind of ritual, so is there a ceremonial aspect to this piece, too?

KP: It’s totally a ritual or a little ceremony. Each incense stick burns for 15 minutes, so about the span of a meditation. We’ve been burning this incense all over the place, inside and out. We had a ceremony beside an old Bodhi tree. We’ve burned it in university halls and outside people’s windows, in plazas and churches and chapels and even in a crypt.

I love the temporary nature of it and how ephemeral it is. You burn it, and then the whole thing’s gone except for a little pile of ashes.

AS: For centuries, religion provided a vessel for experiencing the sacred through architecture, music, poetry and ritual. It seems to me that you’re doing something similar with your work — bringing science and art together to create a secular, planetary mysticism.

KP: I think that sacred feeling is lost today for so many. And we really, really crave it. And we need it to move forward in our relationship to the planet.

For me, it’s nature that provides it most clearly. You just look at a flower, or a seed, or a wave on the sea, or a star in the sky, and you think, “That’s just the most astonishing thing. How did it come to be?” And if you pause and just contemplate that a little bit longer, it unlocks this vastness, this moment of total wonder and awe.

AS: That makes me think of a wonderful phrase I’ve heard you use when talking about your work: cathedral thinking.

KP: Yes, I first learned it through Stephen Hawking, and I’ve noticed it coming more into our vocabulary. I think it originally came from the way that people in centuries gone by would plant trees they intended to eventually become the beams of a cathedral. I love that idea of being able to expand our time horizons to reach our future ancestors.

AS: Which leads us straight to the last work I wanted to ask you about — your Future Library Project in Oslo, Norway.

KP: The Future Library is absolutely a kind of cathedral thinking. We’re planting trees, and in 100 years, these trees will become books. One hundred books, written by 100 authors — one every year between now and the year 2114.

Margaret Atwood wrote the first text and she came back to Oslo this year to visit her manuscript, which was a wonderful experience. The texts are in a room made of wood that we cut when we were first harvesting the forest and planting the trees. Inside are drawers made of cast glass and you can see the authors’ names on the glass and catch just a glimpse of their manuscripts.

AS: And nobody will be able to read these for 100 years? So most of the authors will be dead. You and I will be dead. But maybe your children will be alive.

KP: Hopefully. My son is 7 and he’s very much being trained up to take over the Future Library.

Yes, most of us who are alive now won’t be alive then. But we will hit a point, sometime in the coming 90 years, when more and more people and authors will be alive to read the books. So that’s an interesting concertina of time, from us —the most distant ancestors of the project — to the 99th author. I wonder who that will be!

AS: We hear so much today about the problems we’re leaving to our children and grandchildren. And yet in the midst of that, here’s this opportunity to leave them a gift. Because that’s what this library is — a gift for the future. It brings the future closer, don’t you think?

KP: I envisage the first reader, whoever they are — whoever you are — will open the first page in a very different landscape than we live in right now. That’s both hard to comprehend and also not so hard. When we think about it in terms of family, in terms of grandparents or grandchildren, it’s really not so far away. And yet it’s such an important time horizon.