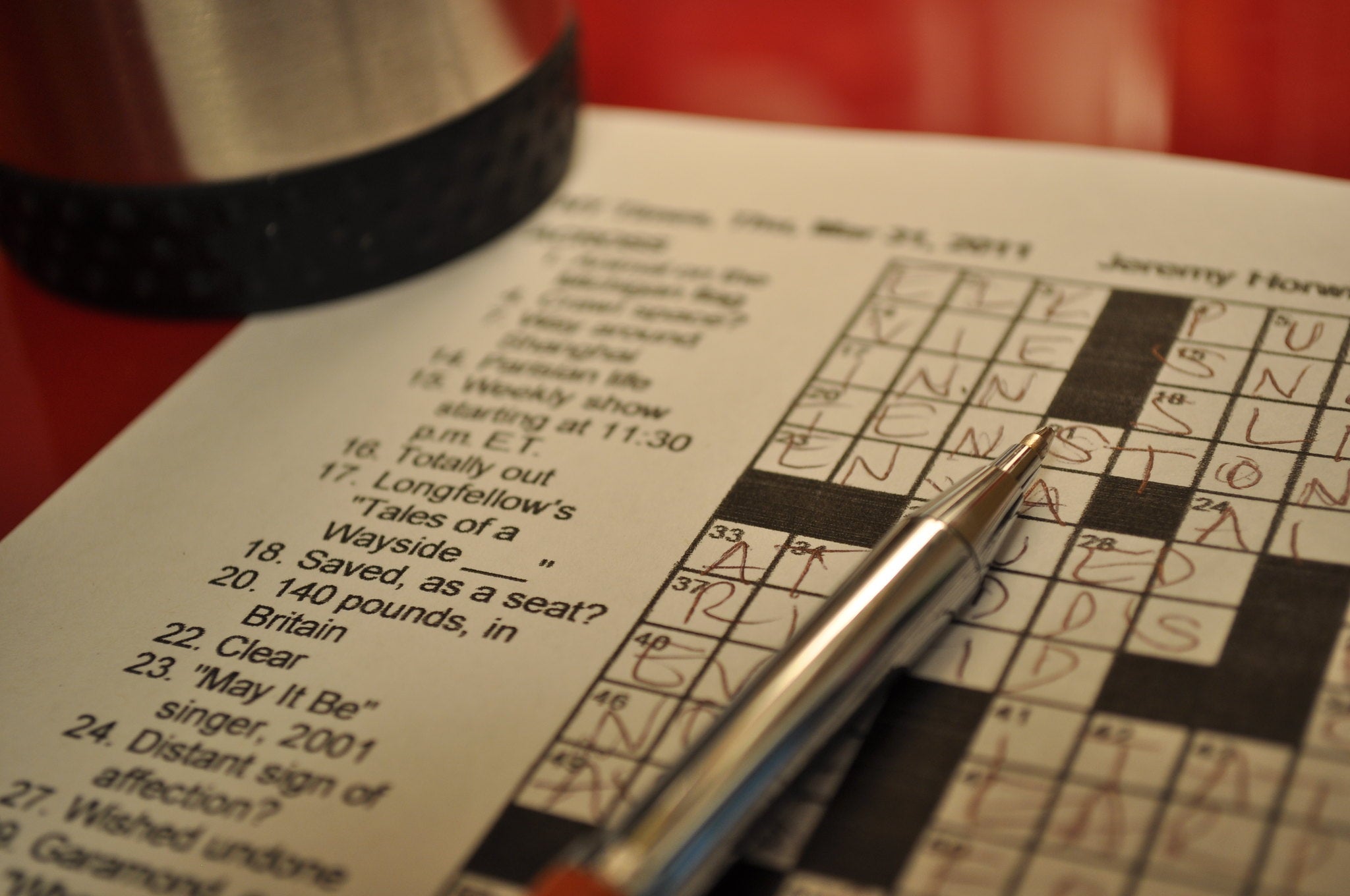

Anna Shechtman first learned there were real human beings behind crossword puzzles when she was 15. She saw the documentary film “Wordplay,” went home and started plotting crossword puzzles on her graph paper from geometry class.

She sent puzzles to famed New York Times crossword maker Will Shortz (featured in Wordplay), who encouraged her, and she published her first crossword in The New York Times at age 19.

Shechtman eventually became Shortz’s assistant at the Times, and now creates crosswords regularly for The New Yorker.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She talked with Shannon Henry Kleiber for “To the Best of Our Knowledge” about the feminist history of crossword puzzles and how crosswords help us share a common language.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Shannon Henry Kleiber: You’ve introduced words to crossword puzzles that no other constructor has used. What are some of those words?

Anna Shechtman: Every puzzle is an index of its maker and her fixations and preoccupations and joys. Some of the early words I introduced were “vine-ripe,” and “gay anthem.” I tried to get the term “male gaze” onto the puzzle. I lost that battle with Will Shortz.

SHK: Because it wasn’t puzzle-worthy?

AS: At the time, yes, it wasn’t understood to be puzzle-worthy.

When I was Shortz’s assistant, I went up to his home office in Westchester, New York. We sat at his desk and we wrote new clues for up to 95 percent of the words in every crossword puzzle, which meant just a tremendous amount of basically free associating together. I was a 23-year-old from Lower Manhattan, and he was in his 60s from rural Indiana. So you can imagine that our frames of reference and also our sense of what is puzzle-worthy would be really different.

And it ends up being a quite political question because it has to do with who is your imagined audience for the puzzle? He wanted the puzzle to be as inclusive as possible. But what that meant for him at the time, and I know it’s evolved since then, was that he wanted as many people to be able to solve the puzzle as possible. And so as a result, he didn’t want to include words that, at the time, he called niche. And that always stabbed me in the heart. Because it basically meant words that were marked by various subcultures — queer culture, Black culture, women’s culture.

SHK: If you take those away, then there’s a whole part of the world you’re not including.

AS: Exactly. And a lot of the ones that didn’t make into puzzles would be proper names. So Laverne Cox, Gucci Mane, or an entire crossword puzzle based around the idea of WNBA teams. And once you start to see these words on the page, you can see a pattern develop. Marie Kondo is another one. They tend to come from nonwhite cultures or women’s culture.

Certainly my editors at The New Yorker make a real point of trying to diversify the words that we understand to be common knowledge or general knowledge. But it has not been necessarily easy, in part because there are some people — and I get the impulse — who say, “Why politicize this pastime?” A friend of mine put “reparations” on a puzzle and a grumpy comments section person said, “Why do I have to think about reparations when I’m solving a crossword puzzle?”

For those of us who do see the value in increasing the kinds of frames of reference and diversity of language that make their way into the crossword puzzle, we would say, “Well, the whole thing is political from the beginning because that grid is legislating the borders or patrolling the borders of what is supposed to be common, whether that’s a national culture or creating a kind of shared sense of what we all think is worth knowing.”

SHK: So is the job of a crossword puzzle to entertain and to challenge? Is it to help us form a more common knowledge together that makes us feel like we’re all part of the same community?

AS: I think it’s absolutely both. For me, I’m trying to imagine a solver. What are they going to like? And my sense is that every time that I feel really satisfied when solving, it’s because I’ve had to really work to play with language to get the answer. A clue I wrote recently was “kingdom for a horse” which is a line from Shakespeare. And the answer is “Animalia.” So that’s literally the kingdom for horses.

It’s also really gratifying to see a word or phrase that maybe you wouldn’t expect to see in a puzzle. I remember the first time this happened to me. It was a puzzle that came out and it had “Soulja Boy Tell Em” in the puzzle. And I just thought, that’s so strange. That’s the music I’m listening to on the radio. And there it is in a crossword puzzle.

And I think there is a clash of expectations there, but also a sense of recognition. This puzzle is for me in a certain way, but for me and also us. Because you know that hundreds, thousands, maybe millions of other solvers are having that experience.

SHK: That makes me think about how the crossword puzzle, especially because it’s daily for instance in the Times, is also a historical document in a lot of ways. You might go back and think about how something happened during a certain war or political upheaval. How do crosswords tell history?

AS: Both World Wars were really inflection points for the crossword. During World War I was the start of what cultural historians call the crossword craze. This was really a nutty time. There was an obsession with crossword puzzles in a way that exceeds anything of my lifetime. It far exceeds even Pokemon or Tamagotchi.

SHK: Why was that?

AS: Margaret Farrar, who ended up becoming the first editor of The New York Times crossword puzzles, (during World War II, because the Times had famously held off initiating a crossword puzzle, thinking that it was a gateway to other debased forms like classifieds and comics), used to say, “You can’t think of your troubles while solving a crossword.” Which is interesting because, as you say, if you go back and look at puzzles from around the time Margaret started editing them, they’re filled with references to World War II, to all sorts of cities along the Eastern and Western Front, different battles, different warships and warheads. They’re filled with these words, even though you can’t think of your troubles while solving them.

But during the crossword craze of World War I and into the 20s, there were all these fears. Baseball managers were afraid that the grid would replace the diamond as America’s pastime, or hotels would put encyclopedias and dictionaries next to the Bible and in their rooms. And there was a run on encyclopedias at the bookstore and the library.

But one of the strangest things I found from my research is that — and this goes back to how sort of woman-coded the early crossword puzzle was both in the people who are writing it and also what people thought of when they thought of crossword puzzles — is that there’s so much ephemera that links the new woman or the flapper to the crossword puzzle. So you’ll have cartoons that show a woman huddled around the grid frantically solving clues while her husband, who’s sort of emasculated, I suppose, is caring for their child. There was one divorce attorney in Ohio who said that he had over 30 cases of divorce where the cause (because there was no fault divorce at the time) was crossword puzzle-itis. The puzzle itself was siphoning off energy from the home and certainly from from the couple. And she was having this illicit affair with crossword puzzles.

SHK: So how then did creating crossword puzzles become such a male-dominated genre?

AS: I think there are three factors. The first had to do with the changes in the workforce. Women who are still expected to do child care and housework and are starting to work outside of the home as well, just don’t have time.

Then there’s the rise of crossword constructing software. People started to get interested in the puzzle as this natural language processing or coding phenomenon, asking, “Can we not necessarily test our own intelligence, but test machine intelligence or artificial intelligence?” If you look at the history of computing, this question — what can a computer do better than a human? — so often ends up being, “Can a computer do X better than a woman can?” Because the work that a computer has historically been programmed to do is clerical work. Work that was largely women’s work or work that women were allowed to do with the idea that it was sort of an extension of the home.

And in the ’60s or ’70s, you start to see the image of a nerd who becomes a cultural phenomenon. And we imagine the nerd as a white man, whether it’s “Revenge of the Nerds” from the 1980s or what began to be known in the late ’60s as the computer boy, those early computer programmers.

I know for me, when I started writing crossword puzzles, I was really trying to prove to myself and the world that I was this capital “S” smart girl. The idea of a nerd had a lot of appeal to me. I even liked to identify as a nerd at the time, and sure, I’m still a nerd, fine. But it carried a lot of weight with me. Being a girl nerd was almost an oxymoron to negotiate socially.

SHK: You were part of a group who wrote a letter to The New York Times trying to make crossword puzzles more diverse. Tell me about that letter.

AS: It was at the start of the pandemic, and it was inspired by the fact that an assistant of Will Shortz’s at the time reached out to me. She was the only woman on the staff there and was frustrated because she felt like she was supposed to be a female censor. Her only job was to say, “Well, that’s sexist, don’t put it in a puzzle.”

But in terms of recognizing the breadth of her expertise and intelligence, she felt tokenized. I was happy to be another woman she could vent with. I mean, delighted. And it’s cathartic for me, too. But we got to thinking about what we could actually do. And we love the Times crossword. We love Will Shortz. But it seemed like there were some structural changes that could be made that would make writing crossword puzzles a better experience for women and hopefully, ideally, nonwhite constructors as well.

Although the history of crossword puzzles, as we’ve been talking about, has all these interesting demographic changes around gender, it’s white all the way down. That’s, to me, historically fascinating and a much thornier, harder question to answer because it’s not at all that Black Americans don’t like crosswords or like solving crossword puzzles.

SHK: What did you ask for?

AS: Among the things we asked for was to have more women and people of color represented on the puzzles and games editorial section. Other things we asked for were that constructors can see their proofs before they go out because it’s so personal. I’ve heard of people having the experience of not being able to solve their own puzzle because the clues had changed. But also there could be references that would be taken out that were women-coded or queer-coded that would be straightened up or made less distinctively drawn from something like women’s culture.

So if we get our proofs, we can push back and say, “Hey, this was important to me. I wanted to see more women in the puzzle,” or, “I wanted to see this trans artist I really care about in the puzzle. That’s important to me. Please don’t take that out.” Or, heaven forbid, and this has happened at certain times: “Something is actually offensive. Please don’t run that under my byline.”

SHK: I wanted to ask you about crossword puzzles and the brain. We’re all aging, and we hear it’s a good thing for us to be doing crossword puzzles. Does it help the agility of our brain?

AS: Something that interests me about crossword solving is why people enjoy doing this kind of work. It’s work we do in our leisure hours. I’m sure part of it is people want to exercise that brain muscle, maybe with the hopes of staving off decline. But I think a lot of us also just solve puzzles because we like to.

I’ve always wondered, what is it about this work that’s not work, that’s pleasing? And I think part of it is that in the world we live in, there’s sort of constant work, 24/7 work. And so I think the sense of completion is really rewarding. It’s work that’s not work, but it also provides the satisfaction of just like, I did this and it’s done, as opposed to the endless work we do all the time.