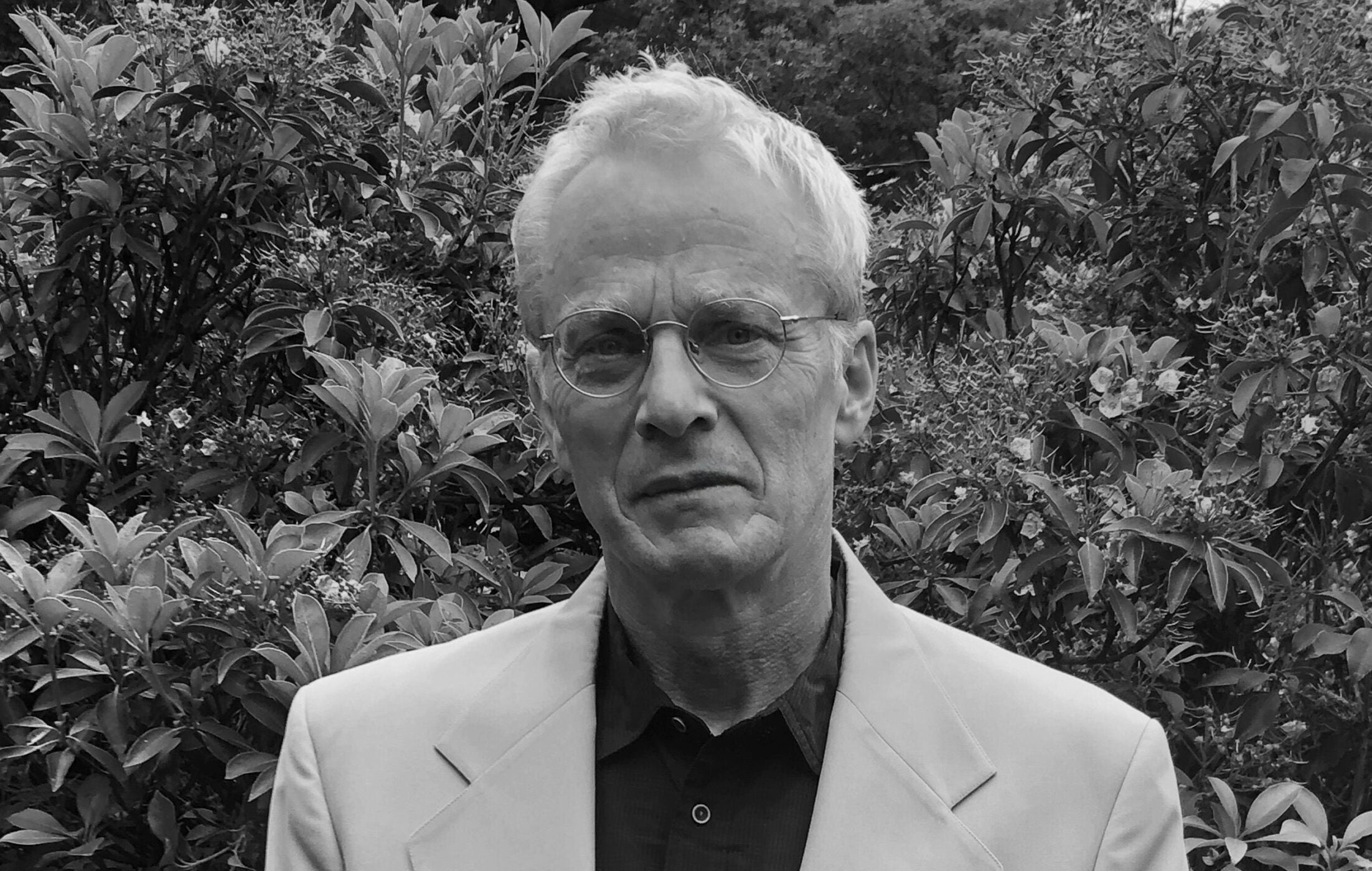

In his 1969 memoirs, English composer Cyril Scott thought back seventy-eight years to a piano teacher who did him a great disservice, and yet played an important part in the development of his career.

When he was twelve years old, Scott and his sister got a new piano teacher. She was not a dishonest person, Scott recalled, but she was a dishonest teacher.

Scott had begun to play the piano before he was old enough to talk, and had long since developed his own haphazard ideas about technique. Had the new teacher been honest, Scott reflected, she would have made him go through the rigors of five-finger exercises for three months, during which he would be forbidden to play anything else on the piano. That was the only approach that would have enabled him to strengthen his fingers and get rid of bad habits.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Instead, she let him go on playing as he had been, when both of them knew that he was only making a show of playing well and would never improve if he went on that way.

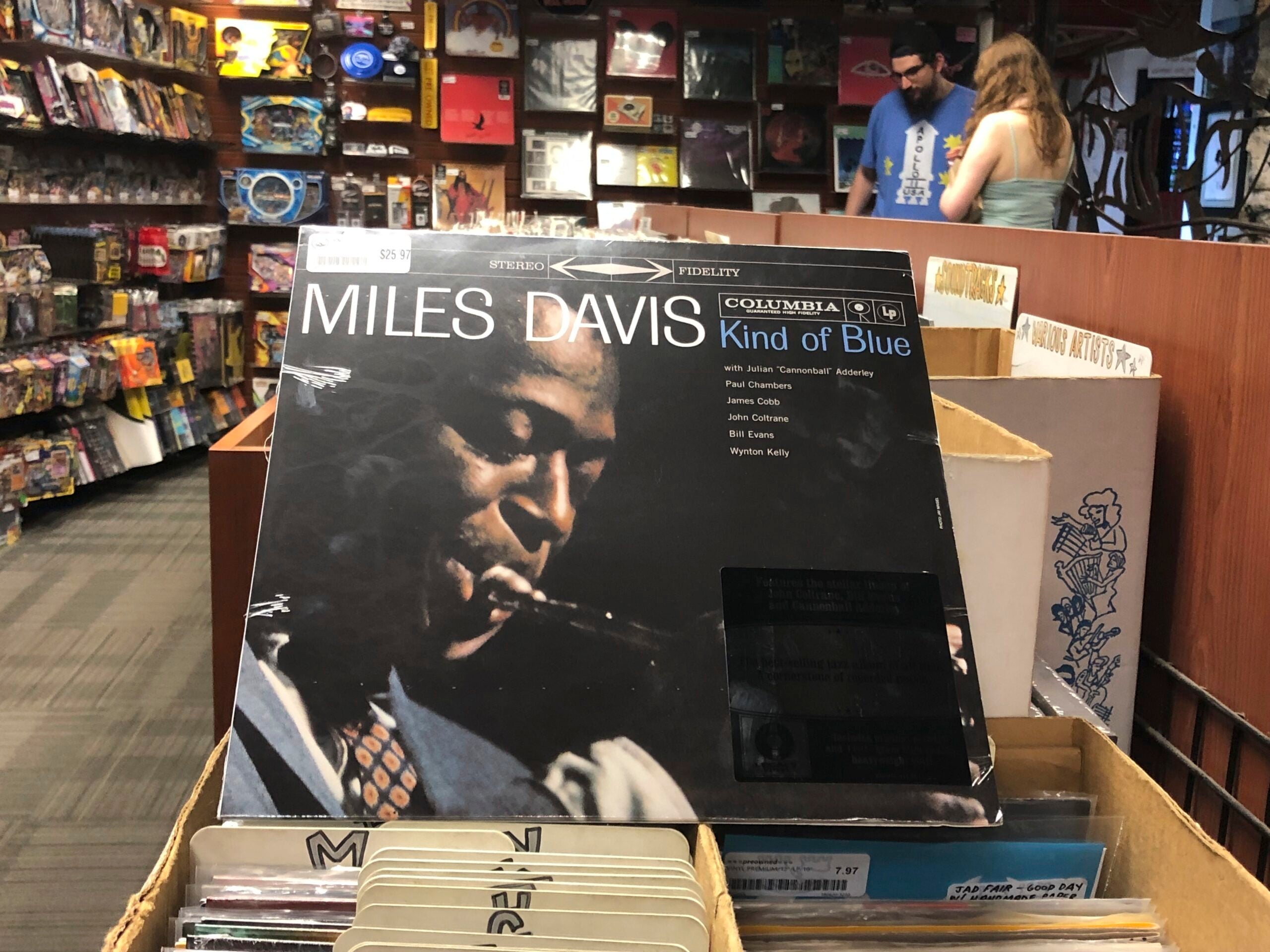

So it went for two years. Then Scott had the first great pianistic experience of his life.

His teacher persuaded Scott’s mother to let him go to nearby Liverpool for a Sunday afternoon concert by the famous Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The virtuoso was at the height of his powers, and he played with such effect that Scott resolved at once to become a musician. He emulated his new idol, right down to the mop-haired look that was the Polish pianist’s trademark.

Within a year, studies in Germany began to mold him into one of the most original writers of twentieth century music.

So while Cyril Scott’s teacher didn’t make him a great pianist after two years of lessons, during a single concert, she did set him on the path to becoming one of England’s great composers.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.