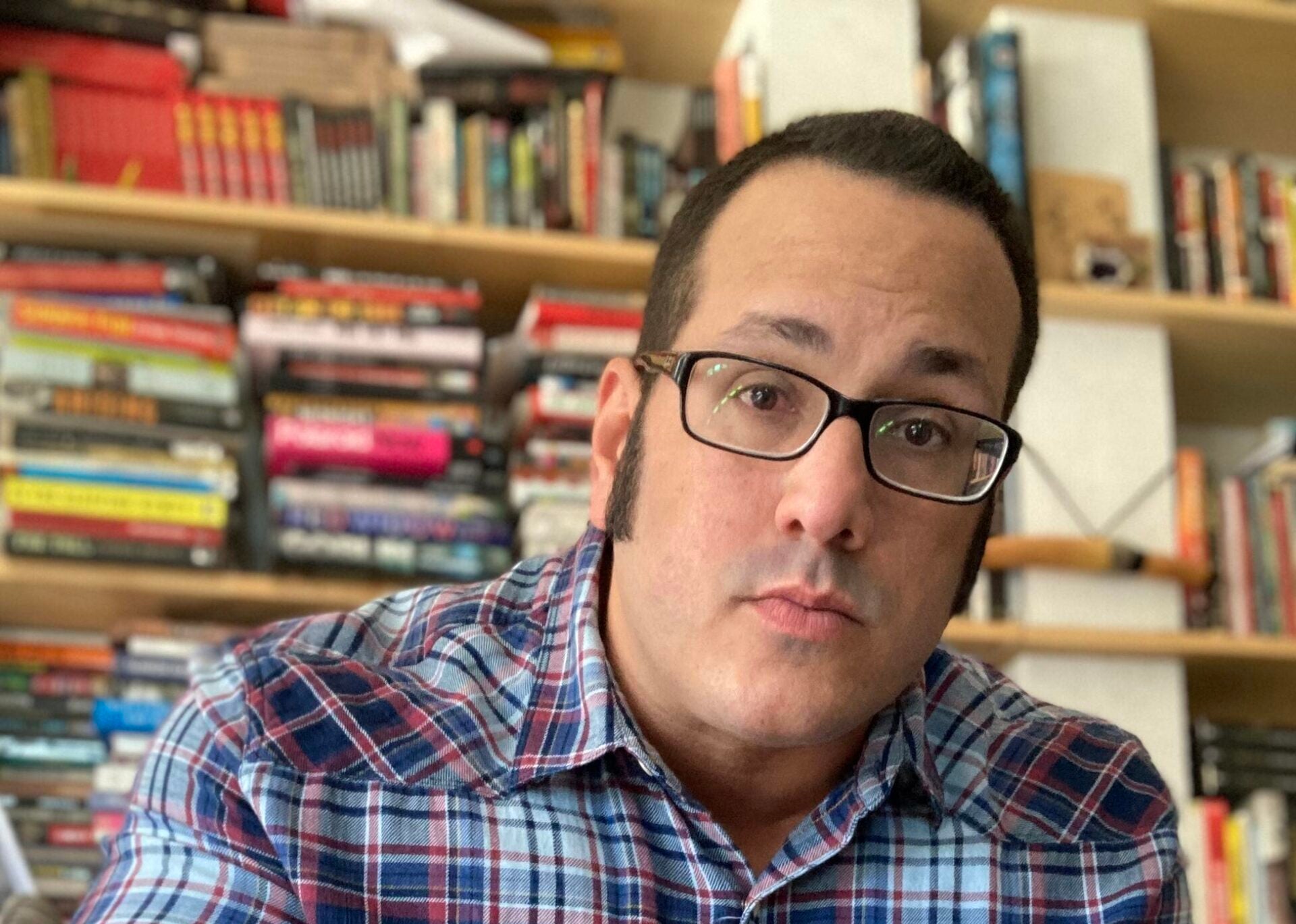

If you have not read any of Gabino Iglesias’ novels, what are you waiting for?

That’s easy for me to say. I only read his two latest a few months ago. They are both amazing.

Iglesias won the Shirley Jackson and the Bram Stoker awards for his novel, “The Devil Takes You Home” in 2022.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

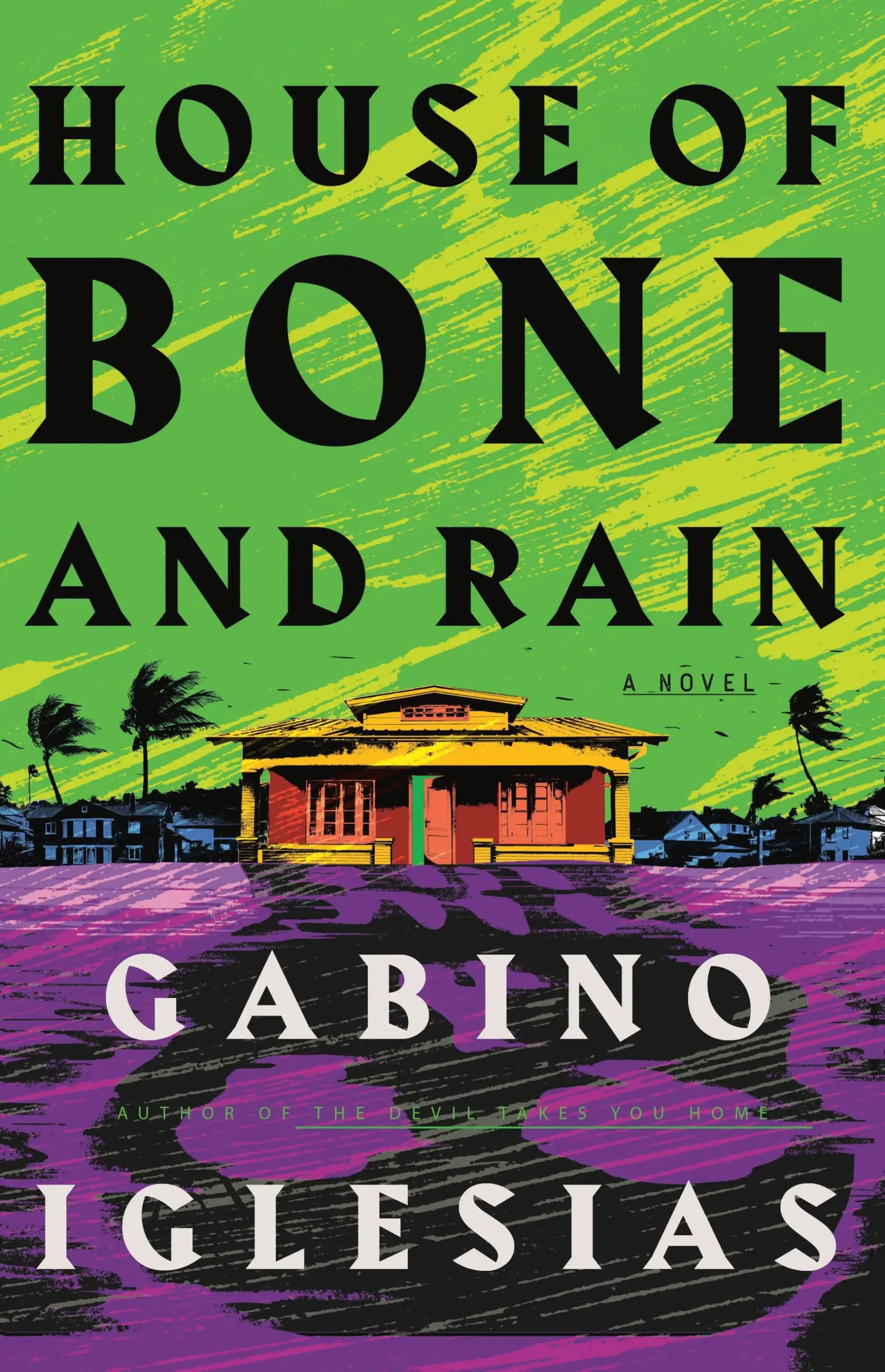

His latest is “House of Bone and Rain,” a beautifully written book inspired by a tragic real-life experience. It’s a coming-of-age story that focuses on five childhood friends.

Iglesias has blended myths, mysticism, horror, hurricanes and life’s harsh realities to create a propulsive page turner that you’ll still be thinking about weeks after you’ve finished reading it. He talked about it with WPR’s “BETA.”

“It was like fiction allows you to take your memories and reshape them into into a story. So that’s what I did.”

Gabino Iglesias

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Gabino Iglesias: (The plot is) plucked from my own life. I had a friend and his mother used to work checking IDs at a club. There was a drive-by shooting in old San Juan, and she took two bullets to the face and dropped that right there.

Obviously, it was painful, and we cried. We hugged each other. And then as soon as that was over, it was like, we need to find the person who did this. And there needs to be some type of holy avenging of your mother’s death.

But this is something that I also talk about in the book. The streets have levels. So the kind of people that get into a car with a gun and just shoot out the window with no discrimination whatsoever, that’s a very dark, very, very bad, very evil, very different level.

So we never found out who did it or enacted any sort of revenge. But I wanted to give us an opportunity to do that. And as soon as I started writing fiction, it was like fiction allows you to take your memories and reshape them into into a story. So that’s what I did.

Doug Gordon: Very well said. How difficult was it for you to write about this real life incident? It must have been tough.

GI: So the thing is, there’s the Latino macho culture where I grew up. You don’t deal with your trauma. I don’t think you’re even allowed to process it. You suppress it. You push it down. And men don’t cry and all that nonsense.

And then digging it out and trying to experience those feelings again so I could write truthfully about that — you go, “Wow, that really hurt.”

And it was another generation. But we never talked to anyone about it. No one went to therapy, went to a group. The grieving process was just anger, and then move on because there’s nothing you can do about it.

So I’m not going to say that it was very painful, but it was certainly very uncomfortable to dig that out and then sit with it for four weeks at a time and ride through the whole thing again.

DG: Hurricane Maria looms large in your novel. You did some research on hurricanes. What did you learn?

GI: I actually didn’t have to. I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. I lived there my entire life. One of my first early memories of the hurricanes was the disaster that was Hurricane Hugo back in 1989.

I wanted to find a perfect character/non-character that gave me the freedom to do certain things in the novel. And not only did I want to write about a hurricane, I realized that for this particular story, if they were going to pursue a vengeance, it was easier to have them do it in the in the post-apocalyptic aftermath of a very big hurricane.

And for better or worse, Hurricane Maria was right there, fresh in my memory. Not being able to speak with my mom. No one has cell phone power. No one has power at home. No one has running water.

So Maria was like the perfect hurricane to throw into this book, and talk about colonialism and not getting help and how many people died, all of that stuff.

DG: And correct me if I’m wrong, but your parents still live in Puerto Rico, right?

GI: My parents are still there. And at any point since Maria, they haven’t had an entire week, Monday through Sunday, of power. They know it’s coming. At some point during the week, power is going to go off.

It could be a couple hours while they’ll fix a little something, or it could be a couple of days. So they need to stay updated with their cans and water bottle. Water, and flashlights, and batteries, and candles and all that stuff.

DG: How do you approach society when you are writing crime fiction and horror fiction?

GI: It’s one of the reasons why I do both. I think they share their obsidian black heart. The core of noir and the core of horror is basically the same. You take these characters who might be gray, morally gray, but not necessarily pure evil, and then you put them through the wringer.

And then the novel is the distillation of that, the result of that, the stuff that you’re left with at the end. It’s really interesting to do that to those characters.

The way that you approach society is always as the keenest observer possible. Just look around. If you want to talk about misogyny, if you want to talk about racism, if you want to talk about politics, if you want to talk about migration, if you want to talk about colonialism, just look around and pay attention.

And then the horror and crime fiction become this wonderful mirror that you just hold on to society and be like, yeah, I’m going to entertain you with some supernatural stuff. But here’s the rest. Here’s how awful we are.

It’s true. It’s not supernatural. So let’s sit with it and be uncomfortable together.