Helen Phillips joined WPR’s “BETA” a while back to talk about her novel, “The Need.”

It was longlisted for the National Book Award in 2019. Motherhood was one of the main themes in the critically-acclaimed novel.

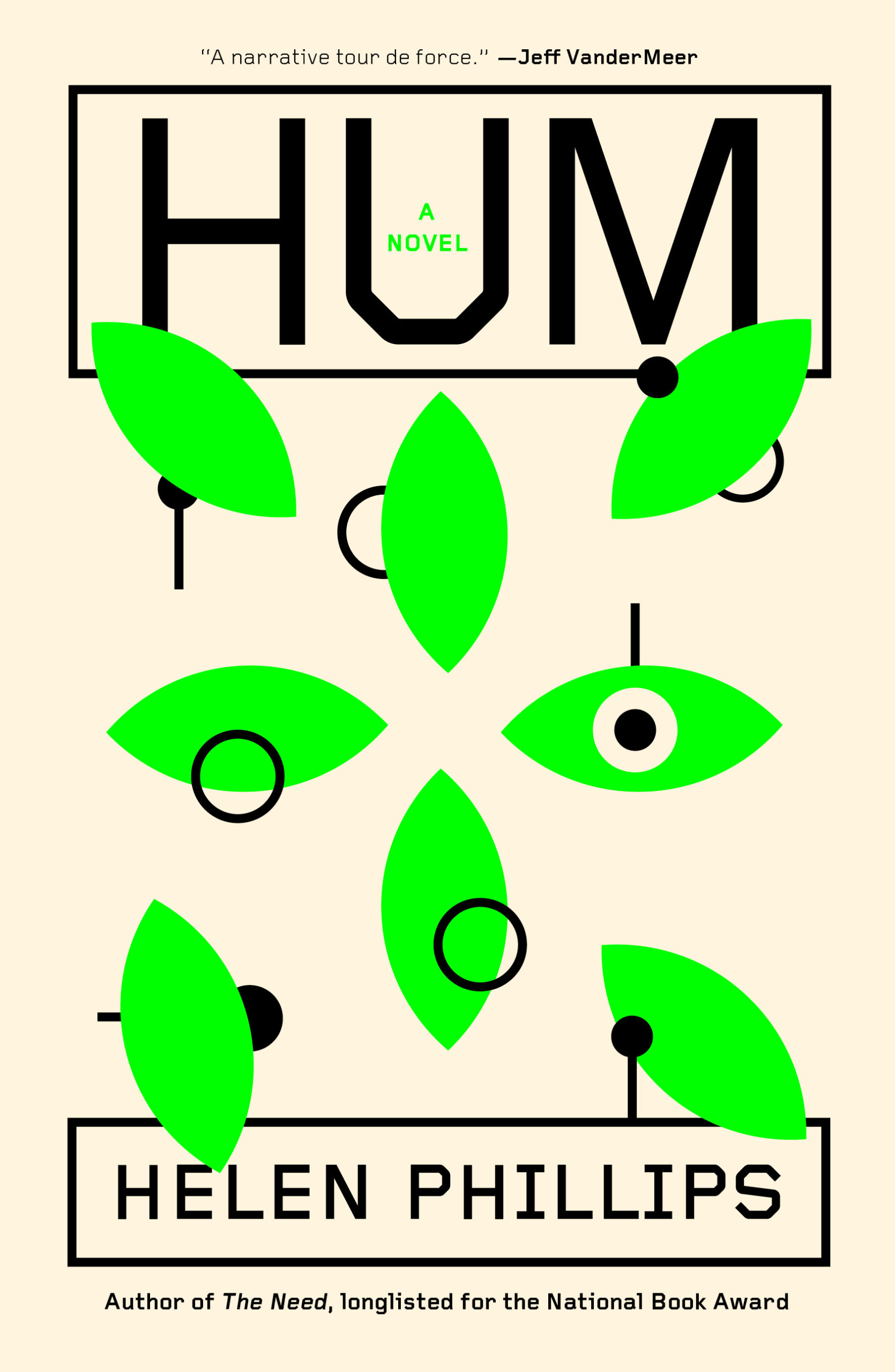

And motherhood plays a big part in Phillips’ latest novel, “Hum.” The protagonist, May Webb, has lost her job to artificial intelligence.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Her family is drowning in debt. So May decides to make some money by participating in an experiment that changes her face so that surveillance cameras cannot recognize it.

“Hum” takes place in a near-future world that has been messed up by climate change and populated by intelligent robots called “hums.”

The “hums” use their torsos to promote and sell products and services to the humans who live there.

“BETA” sat down with Phillips again to talk about how we’re afraid this may be the new annoying Amazonian form of advertising that we will have to deal with. Or are we already dealing with it?

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: Your novels and short stories explore the effects of surveillance capitalism. What is it about surveillance capitalism that interests you?

HP: I’ll answer that by telling a little anecdote — one of the seeds of harm.

One day some years ago, I was walking home from work, and the thought crossed my mind: I really need some new dishrags. I haven’t bought new rags in a while. I arrived home and opened my computer and dishrags were instantaneously advertised to me. I think a lot of us have had experiences along these lines and it was quite an eerie sensation.

Did they enter my mind? How did they know? Did I say it out loud? That feeling of being surveilled.

But then I think I went ahead and bought those rags, because they’re just dishrags. It’s not a big deal. But it did get me going along the line of thinking, OK, what would be the worst possible outcome of that kind of surveillance? Why does this give me such a troubled feeling?

And what would happen if I wrote a novel where I put a character in a situation where that surveillance really leads to much bigger problems than just feeling a little strange that they know you want dishrags?

DG: Very well said. You have created this very interesting world that seems to be set in the near future and is not all that different from our own. It includes these intelligent robots called “hums.” Can you tell us a bit more about the role the “hums” play in this society?

HP: “Hum” is obviously the title of the book, and I’ll use that name as a way of exploring this question … Once I knew that these robots would be called “hums,” I knew that “Hum” would be the title.

And that title is very meaningful to me in the book because I feel like it has a duality in it that is also encapsulated in the characters of the “hums.” So on the one hand, a hum for me can be the low, relentless sound of all of our devices — the simmer of the internet, the simmer of all of our machines, a sound that you can never quite quiet — it’s always there.

And on the other hand, “hum” is a very beautiful word. Maybe it’s someone humming a lullaby to their children. It calls to mind potentially the sacred sound “ohm.”

And that duality of being a machine, a relentless machine, and having this other element that is almost divine or comforting. The “hums” contain both of those sides.

DG: You raise a lot of important questions in “Hum,” like how might we dose our technologies? How might we dose our usage of our planet? How might we dose our children’s independence from us? These are all big questions. And you’ve probably been too busy, but have you come up with any answers to these questions?

HP: I’m glad you bring up that question. And I’m actually going to read the epigraph to the book, which that question really is referring to. So the epigraph to the book is from Paracelsus, who was a physician in the 1400s.

And Paracelsus said: “Poison is in everything, and no thing is without poison. The dosage makes it either a poison or a remedy.”

To me, that is very much a quote that captures how I feel about technology. The technologies that we have are incredible tools and we we can’t get rid of them. But how can we have a good relationship with them? How can we dose them so that they’re a remedy, not a poison? And that quote I selected as the epigraph, because that’s really one of the driving questions of the book. What is the right relationship to have with one?

What is the right relationship to have with your woom? I don’t know that I have arrived at any clear answer as the book is really existing in that gray area. But certainly personally, I try to have a time where I take a break from my email, take a break from my phone, put it away and really remove my eyes from the screen and try to ground myself fully in the physical world and the people around me.