The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

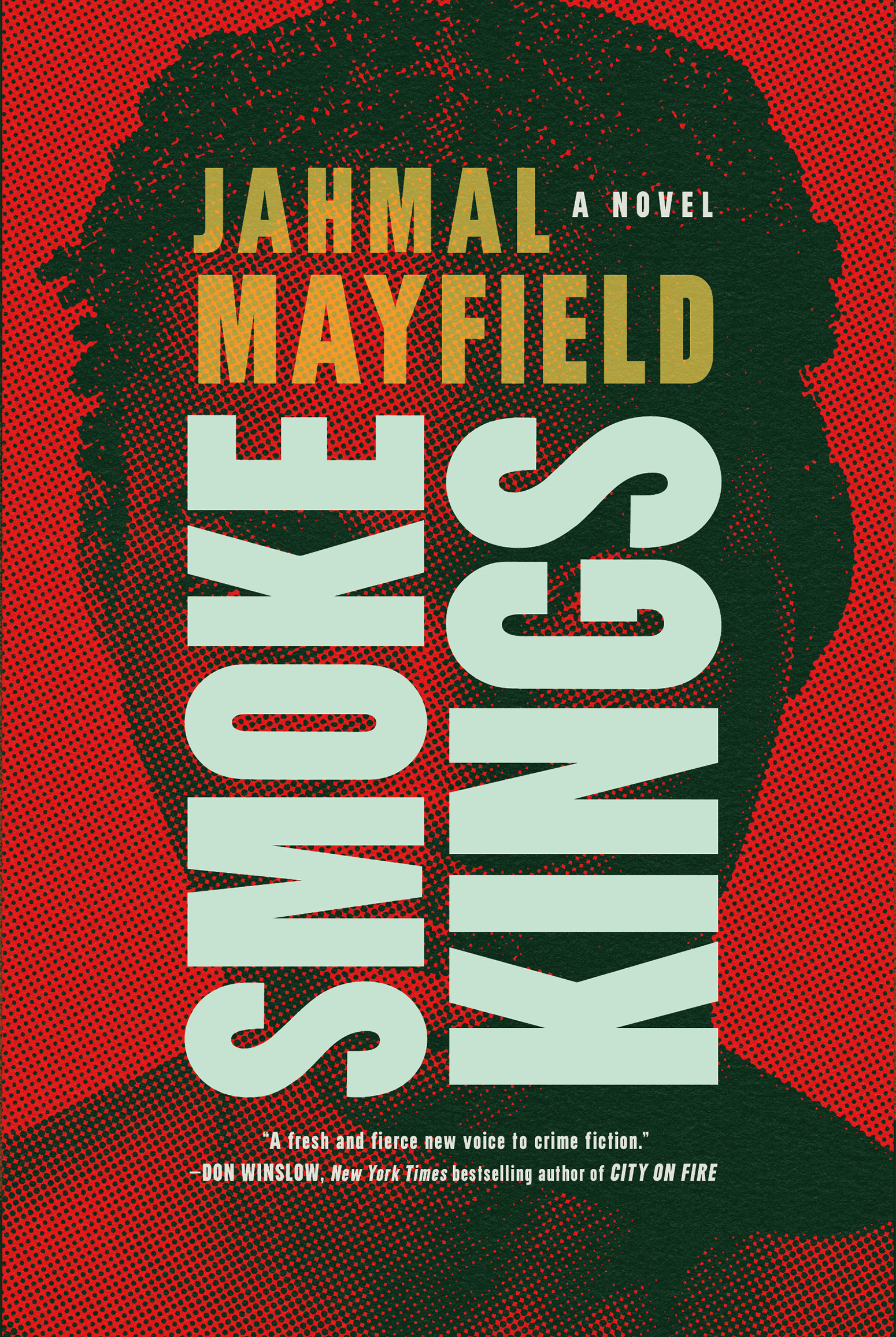

If you’re looking for a noir thriller that you won’t be able to put down, look no further than Jahmal Mayfield’s debut novel, “Smoke Kings.”

As the best-selling crime novelist Don Winslow says, it’s “a stunning book that takes the reader on an intense and harrowing journey that is truly unforgettable. Consider me a big fan.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Mayfield has added something that you rarely see explored in noir novels – “reparations.” The idea of reparations for slavery has been around for a long time but no federal reparation bills have been passed.

In “Smoke Kings,” a group of grieving friends kidnap the relatives of people who have committed hate crimes. The friends force these relatives to pay reparations to a community fund.

Mayfield spoke with WPR’s “BETA” about race riots, his personal experiences and having open conversations in order to move forward.

Doug Gordon: What inspired you to write “Smoke Kings”?

Jahmal Mayfield: It’s an interesting question. So, first of all, I’ll go back.

It kind of gestated in my mind for a number of years. In 2018, my little cousin was murdered. I remember standing on the street — we were having the candlelight vigil. It just didn’t feel like enough. So I had this kind of, a sense of overwhelming sadness. Young Black men are dying, and the best we can come up with are candlelight vigils and Twitter hashtags and memorial t-shirts.

Then two years later, we had the summer of George Floyd, and there was a video that went viral from poet and activist Kimberly Jones. And I had never seen this marriage of anger and intelligence quite like I did in that video. I’ve seen anger. I’ve seen people that were angry about, you know, circumstances, and can talk about that. She was very passionate, but she was also very just intelligent.

And she talked about the social contract that had been broken. And she was basically standing in the middle of a war zone, you know, the rioters and looters in Minneapolis. And she was saying we don’t care about this community.

Now the contract has been broken. And it was broken with Tulsa, Oklahoma, Black Wall Street and all these different things.

She got to the end of the video and she said, “They are lucky that what Black people are looking for is equality and not revenge.” And that line just stuck with me. I thought, man, that’d be a great what-if jumping point premise for an thriller.

DG: Where does the title “Smoke Kings” come from?

JM: That comes from a W. E. B. DuBois poem (“The Song of the Smoke”). I think it was 1907, and it was a poem really about Black empowerment.

There’s that first line, “I am the Smoke King/I am black!” And when I came across that, I thought, “Wow, that’s exactly one of the things that I’m trying to get across.”

And I thought it would be cool to not only bring that history a little bit into the novel, but also give a nod to W.E.B. Dubois with the title.

DG: It’s a great poem. Let’s talk a bit about the characters in your book. Can you tell us about the inciting incident that Nate Evers, a young Black political activist, has to deal with?

JM: That comes from, as I shared before, my own personal experience. Nate has a little cousin that early on in the book, we talk about the fact that this little cousin, Darius, is murdered and Nate is dealing with the rage and the anger that he feels in that moment. And feeling like, “I can’t just let this be another young Black man that dies and there’s no equal response.”

So in his mind, he feels an equal response is to hatch this somewhat crazy scheme to kidnap the descendants’ perpetrators of hate crimes from the past and charge them with reparations.

DG: We hear about reparations every so often, but nothing seems to happen. Do you have any optimism that at some point reparations may be become a reality?

JM: That’s a good question. We’ve seen so much progress in so many areas. I think the pain that Black folks in this country have felt for a long time is still very much a conversation that is happening, and there’s still a number of people that feel skeptical about that pain and about that hurt.

And so, if you’re going to get to the point of anyone being at a place where they feel like it’s justifiable to pay out reparations, then we have to deal with that skepticism first. And I think we have a long way to go as it pertains to that.

DG: Yeah. Which is probably truly the case. But it’s quite sad that we still have such a long way to go, isn’t it?

JM: Yeah. One of the things I tell everyone — and this was actually one of the conversations that I tried to bring about in “Smoke Kings” — is certainly Black folks have been marginalized in many instances.

But there are women that have been marginalized and Jewish people, and so forth and so on. And I think one of the things that we have to do a better job of is expressing our pain and not dealing with it in silence, which we tend to do.

Many folks have put their heads down. They don’t talk about the microaggressions they’re dealing with at work or any of those things. So first of all, we have to talk about these things openly, and then we have to get comfortable having uncomfortable conversations when we do have those discussions.