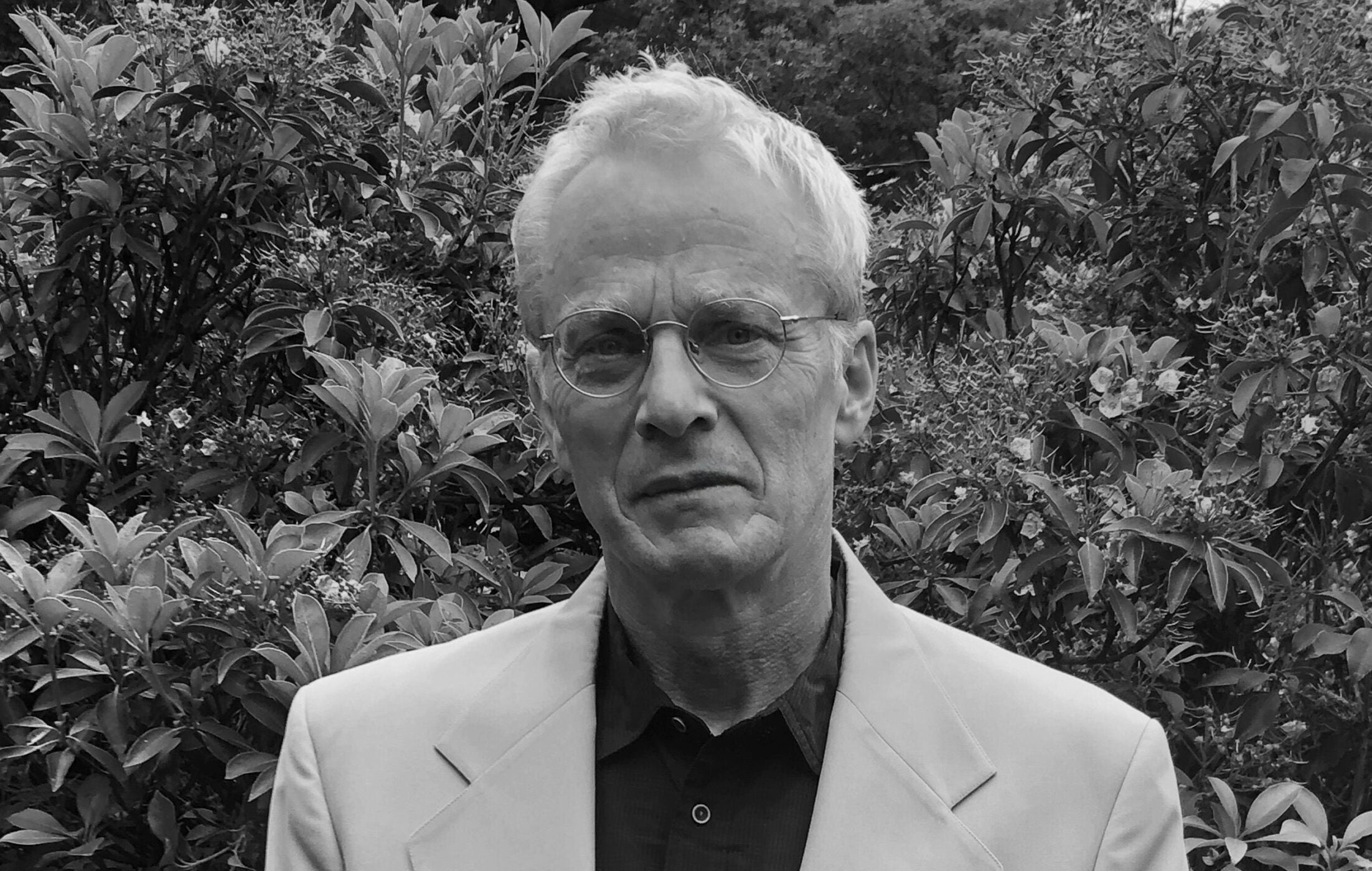

James Kaplan tells the story of the three geniuses who were the main force behind Miles Davis’ 1959 recording of “Kind of Blue.”

Kaplan said after his first book, his editor, Scott Moyers, suggested that the next focus on “Kind of Blue” and the musicians behind it. So became his latest, “3 Shades of Blue.”

“I built on Scott’s idea about a book about the three, arguably the three geniuses, of ‘Kind of Blue.’ That’s Miles and Coltrane and Bill Evans,” Kaplan told WPR’s “BETA.” “What about them as men and musicians before, during and after the making of this timeless album?”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Steve Gotcher: In the summer of 1959, we saw the release of Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue,” which featured many great players, including Bill Evans on piano and tenor saxophone and player John Coltrane. What brought these musicians together for this recording?

James Kaplan: It was who brought them together. It was Miles Davis. Miles had an artistic temperament very similar to Picasso. He was restless. He was always moving on to the next thing. He couldn’t stand staying in place. Like Picasso, he also had a great artist’s sure feeling about how to place the various components of his art.

There’s a great story about Bill Evans, who came to New York City in 1955 from the hinterlands, a very young man, 29 years old, determined to make it jazz or go home. He played a lot of weddings, bar mitzvahs, and dances. He also got a job at the Village Vanguard, playing between sets of the Modern Jazz Quartet. The Modern Jazz Quartet were then superstars, and Bill Evans was nobody.

The place went dead silent when the Modern Jazz Quartet played at the Vanguard. When they took their break, Bill Evans started to play because it was his job to play during their break. The dishes began to rattle, the glasses, the silverware. People started talking. One night, Bill Evans encountered all these distractions while trying to play his beautifully subtle piano. He looks down at the end of the grand piano, and there, under the lid, are the penetrating eyes of Miles Davis.

Miles is there checking out Evans, and a week later, Miles calls Bill Evans on the phone out of the blue and says, join my band. And when Miles said, “Join my band,” you join Mile’s band. A similar thing happened with Coltrane and everybody else on that album.

SG: Let’s talk about the studio session. What were they like? Were they doing improvisation, or were they doing written out pieces?

JK: Miles was the great exponent of improvisation, so he knew that the musicians he had hired for the kind of blue sessions were so brilliant that all he had to show them ahead of time was the tiniest little sketch of what he had in mind.

For each number, he would write out a couple of musical notes, sketch them out on a napkin or a piece of paper, and say something to them, a little bit about who would solo where, who would solo when, and what the chord progression was going to be. And then they were off.

We must remember what Bill Evans said, that no musician ever goes into a studio for a recording session on a Wednesday morning and knows he’s going to make a great album — it doesn’t work that way. These were two sessions in March and April of 1959, and the fantastic thing is that every complete take on that album, except for one, was a first take.

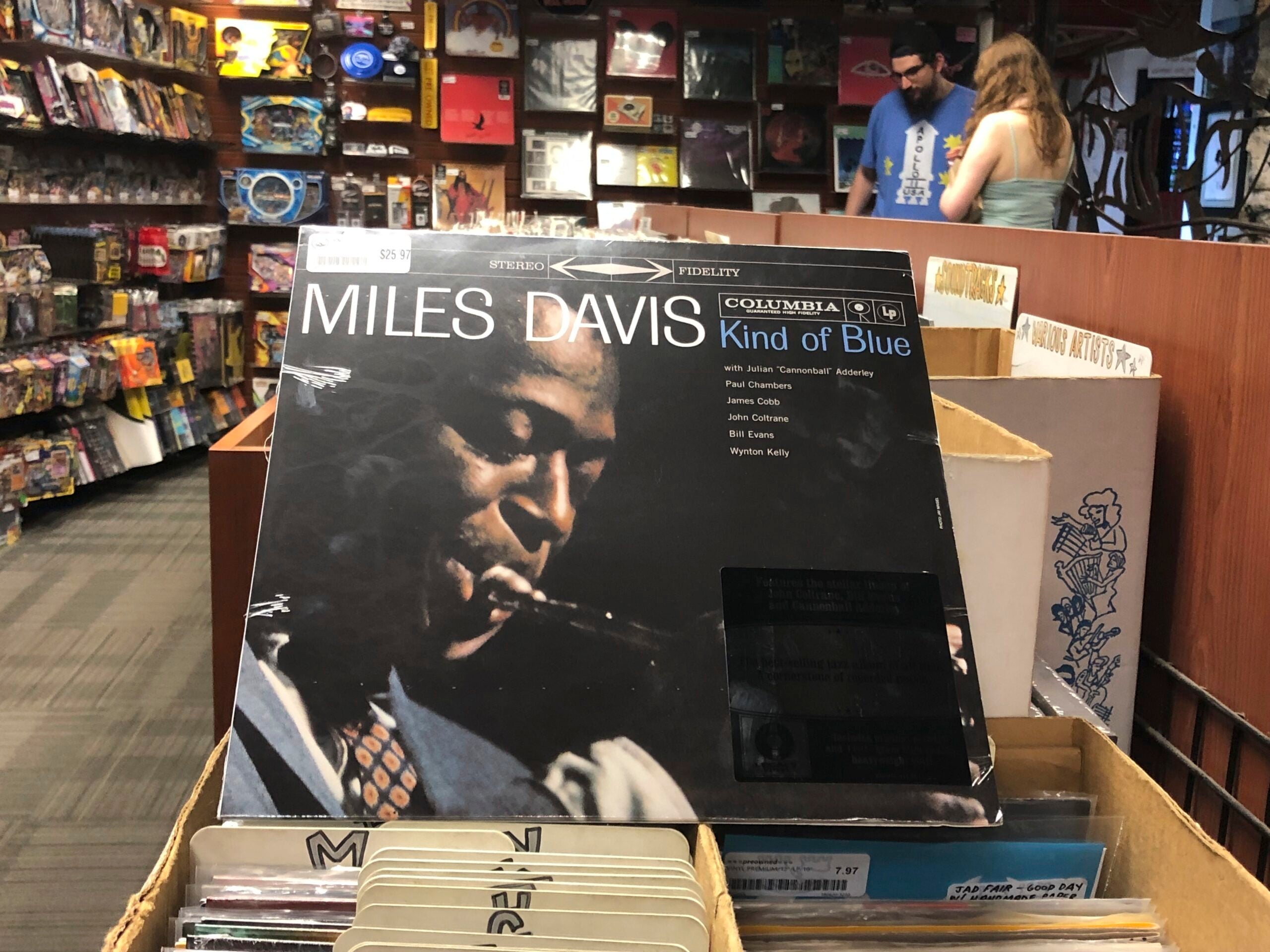

SG: Wow. That’s amazing. How was “Kind of Blue” received when it first came out?

JK: “Kind of Blue” was received with a certain amount of puzzlement in many quarters. It was a brand new thing, a brand new sound.

It was extremely quiet, but much too quiet for many critics. Several critics said, “This is pretty music, but it lacks force. It lacks power. It needs to be more dynamic. We don’t like it.”

But some critics were astute enough to realize this was genius. This was history, and this was an album like no other. It truly is an album that’s outside of time.

SG: When did “Kind of Blue” become recognized as the legendary album it is today?

JK: I think it took a few years. Sales were steady but not gigantic. There weren’t the initial big sales there had been for the Columbia albums Miles did with Gil Evans. “Kind of Blue” took a while to get its firm footing commercially, but then it just held on and held on and kept selling first in gradual increments and then steeper increments. And it has just continued to hold on to this day.

SG: After “Kind of Blue,” Miles Davis, Bill Evans and John Coltrane headed in different directions and had great solo careers. Where did John Coltrane take his music?

JK: He took his music to the outer limits of the universe. And within, I think, it was just about three weeks after the second and final session for “Kind of Blue” that Coltrane went and recorded “The Giant Steps,” which was precisely what the title says. It was a giant step ahead for the tenor saxophone, jazz and Coltrane. He had to find his own path.

After imitating Charlie Parker, he had to not imitate Charlie Parker and find his own way. And he did. Coltrane had a way of taking chords and finding parts to chords in jazz that nobody had ever thought of before. Coltrane found new notes to play and new astronomical heights to take his playing.

That even left a lot of jazz musicians behind. There were many people who grew impatient with Coltrane, but Coltrane had an artistic path. He had a creative trajectory that was very steep and very difficult after “A Love Supreme,” which is such a masterpiece. He began to explore these interplanetary realms with the saxophone, and he took the art farther than anybody had before.

SG: What about Bill Evans? He took a different tack.

JK: Many people complain that Bill Evans didn’t go very far artistically. That’s not true. One of the wonderful interviews I got to do for my book was with the great young pianist, composer and brilliant man named John Batiste, who was the bandleader on “The Colbert Show” for a while. Jon Batiste greatly respects Bill Evans and felt that, in many ways, Bill Evans went further than Coltrane or Miles. Bill Evans played in the trio format for the rest of his short career. He played beautiful, beautiful, very subtle music, highly influenced by Western classical moderns.

He had incomparable touch and subtlety. I think that his touch and subtlety were vitiated in his later years by his switching from heroin to cocaine. Suddenly, a pianist who had always slumped down low over the keys to coax the most subtle sounds out of the piano was sitting bolt upright and playing a little faster. Arguably, that was the influence of cocaine.

SG: Miles Davis took probably the most experimental path, changing his style from album to album until he got to very electronic music. How does his career progress?

JK: He incorporates much of the quiet he found with “Kind of Blue,” but then he picks up electronic instruments. He becomes more and more compromised physically. The trumpet is an exceptionally physically difficult instrument to play. He became more of, almost like an impresario or a conductor than a player among players in his later albums. He switched from trumpet to electronic organ and electronic keyboard. In many of his concerts in the 1970s and ‘80s, he mainly played keyboard and maybe an occasional single note on the trumpet. It was experimental but also necessary, given his physical limitations.

You had albums as varied as “In A Silent Way,” “Filles de Kilimanjaro,” “Jack Johnson,” and “On the Corner.” Miles was fascinated by rap. Miles loved Sly Stone. He loved Prince. He wanted to forge artistic alliances with these great young artists. Miles saw the future.

SG: If you had the power of seeing into the future, how do you think people will look at kind of blue in 2059?

JK: 2059, that’s not that far away. It’s 35 years from now. So, it’s going to continue on its timeless path. I believe that as long as people are listening to music, as long as there is music, there will be “Kind of Blue.”