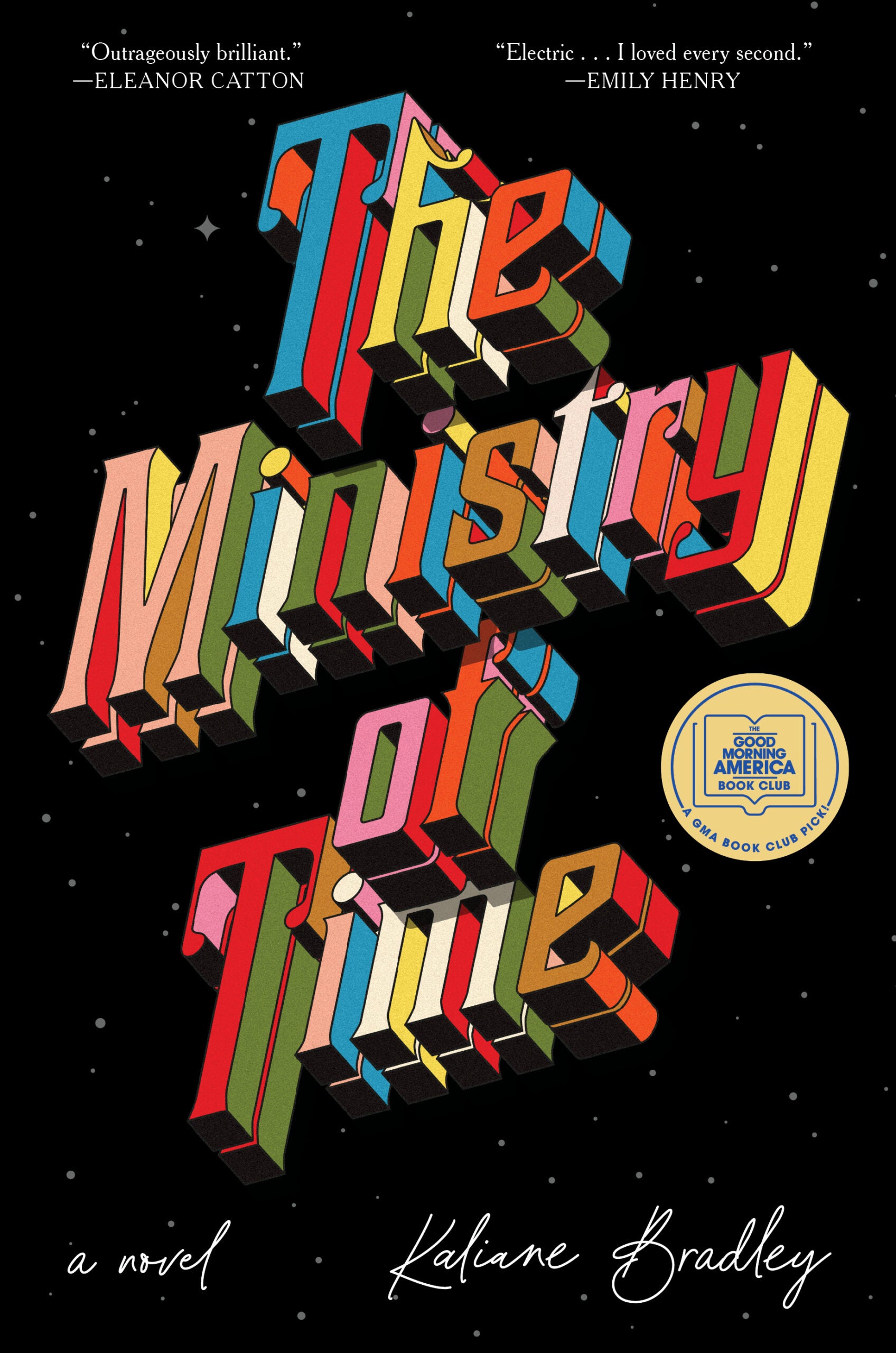

If you’re looking for original, beautifully written books about time travel, workplace comedy, spy novels and romance, we’re going to make things easy for you. You only need one book: “The Ministry of Time” by Kaliane Bradley.

“The Ministry of Time,” Bradley’s brilliant debut novel, is set in the near future. A relatively new government ministry is collecting expatriates to discover if time travel is possible.

The BBC is adapting “The Ministry of Time” into a six-part series and A24 Films will produce it.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Bradley has done her homework and has delivered a convincing case for the possibility of time travel, which she shares with WPR’s “BETA.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: The origin story of your novel goes back to 2021, during the U.K. COVID-19 lockdown. What happened?

Kaliane Bradley: During the 2021 lockdown, I started watching a TV series called “The Terror,” which I thought was absolutely wonderful. It’s a 10-part series by AMC, which is about Sir John Franklin’s lost expedition to the Arctic.

So in 1845, Sir John Franklin took two ships, 129 men, to try and discover the Northwest Passage. And they vanished. All 129 men died in the Arctic. Both ships were never found, or at least not found until, I think, 2016 and 2018.

“And I started writing the first version of ‘The Ministry of Time’ for them as a kind of joke, actually. What would it be like if your favorite polar explorer lived in your house?”

Kaliane Bradley

But it is also a TV series set during the Arctic nights, so it’s very dark — 66 named characters, most of whom are white men with mutton chops, wearing big Arctic great coats. So quite difficult to tell apart. So I thought, I will just go and check Wikipedia.

I went to the Wikipedia page and I ran across this name, Graham Gore. I hadn’t actually noticed Graham Gore in the TV series. He’s not actually a major character in history. He’s kind of a footnote, actually, but I thought, that’s an interesting name. I’m sitting on my sofa. I can’t go outside. I’m not doing anything.

I may as well just click on that, find out who he is. I got to his Wikipedia page and I saw the photo.

And I thought, God, I bet that guy would be great to have around during lockdown. He sounds amazing. I was becoming interested in this expedition. I was becoming interested in this very minor character from history.

I ended up finding online a community of amateur polar exploration enthusiasts who were very kind enough to share some of their research and their knowledge.

And I started writing the first version of “The Ministry of Time” for them as a kind of joke, actually. What would it be like if your favorite polar explorer lived in your house?

DG: I want to get back to the Franklin expedition for a moment, because it is fascinating. And you’ve said that part of that whole expedition is hubris. Can you tell us about that?

KB: These men went to the Arctic, intending to discover passages that they weren’t sure existed, they assumed existed, and they assumed if once they found it, it would be very useful for the United Kingdom to have this passage to the Arctic.

But they went without an Inuit interpreter even. They just assumed they would get there and it would be plain sailing. They wouldn’t wear the the clothing that the Inuit wore. They wouldn’t wear furs. They wouldn’t use Inuit style sleds, because if they started using Inuit technology, it would be considered uncivilized.

They wanted to take England with them and just transplant it into the Arctic, which is a ridiculous, preposterous, stupid thing to do.

It’s just sort of preposterous to me that these men believed so much in the idea of making history, believing they were making history, that history was something they could grasp and mold themselves. They just went to the Arctic and died there without first checking in with the Inuit to make sure it was fine.

DG: I was very impressed by the way you incorporated time travel in such an innovative way. How much cognitive bandwidth did you have to use to to figure out the time travel?

KB: It was tricky. One way I think I did simplify it for myself — and I needed this simplification to make the stakes of the story work — is that it is a time travel novel in which no time travel happens on the page.

It all takes place in the 21st century because the narrator is experiencing it in the 21st century in linear time. But we went through a lot of drafts, and my editors asked a lot of very penetrating questions about the stakes of time travel, because if you can just move back and forth in time and fix things, what are the narrative stakes, actually?

What do you need to change? Do you need to change anything about yourself or your way of connecting with the world if you can just keep rewinding and readjusting?

So we had to place limits on time travel. But also just keeping the idea of different possibilities, different timelines straight was quite tricky. A lot of it involved me pulling back from the idea of time travel as a sci-fi concept and thinking of it more as a a kind of form of narrative, really — as a way of handling time in a novel.

DG: You have said that your unnamed protagonist is British-Cambodian. And you have said that you might be the first British-Cambodian person to publish a novel. Assuming this is the case, what does that mean to you?

KB: That’s a good question. No one’s asked me, but as far as I’m aware, I think I am the first British-Cambodian person to have published a novel in the U.K.

I suppose I’m very happy to have contributed to the amplification of Southeast Asian voices in the U.K. I very much hope that my being published means that there will be many, many more. I may be the first, but I hope a second is very, very close behind me. And I hope the third is very close after that.

I hope that it doesn’t have to feel like an exceptional or remarkable thing. It feels like it’s a natural thing to say that you’re a British-Cambodian writer. I realize the diaspora is not very large in the U.K. in the way it is in the U.S. and in France, but even so, I hope they won’t be the first and only for long.

DG: For the length of time that you are the first British-Cambodian person, does that put pressure on you in terms of writing your future novels?

KB: That’s a really good question. And I think the pressure is mainly coming from me internally. I think if I feel obliged to be British-Cambodian, to be somehow representative of all British-Cambodian writing or British-Cambodian concerns, then there’s going to be a lot of pressure.

But of course, no one ever is perfectly representative of a single ethnicity or marginalized background. So if I think of myself as a writer among writers, I like to imagine myself in conversation with other writers of Southeast Asian heritage and other British writers, actually, and other writers who come from different marginalized backgrounds.

So I think the way I take the pressure off myself is to imagine myself in broader conversation with so many more people, rather than thinking of myself as an exception.