Eloisa Gómez of Milwaukee says there’s a lot of work to be done to get 2020 election information to the city’s Spanish-speaking community. Right now, she’s working with the city’s branch of the League of Women Voters to engage voters, focusing on residents on the South Side.

“We’re providing a lot of bilingual literature, making it culturally appropriate,” she said, “to really attract attention, and to be able to provide non-partisan info, so people make good decisions about it when they vote.”

Gómez wanted to know more about Latin American — or Latino, or Latinx — voters in Milwaukee and Wisconsin, so she submitted a question to WPR as part of the network’s WHYsconsin project. Here’s what she asked:

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“The 2020 elections are a historic milestone for Latinx voters in the U.S. At 13.3 percent, the Latino population has the largest share of the electorate among minority voting populations. How is this changing demographic changing electoral politics now and in the future? More specifically, how does this trend translate to the level of the city of Milwaukee, which has the largest concentration of Latinos in the state of Wisconsin?”

To answer Gómez’s question, WPR’s “Central Time” reached out to Phil Chen, an assistant professor of political science at Beloit College, and Jaime Alvarado, state board secretary for the League of United Latin American Citizens, or LULAC — an advocacy group focused on housing, education, civil rights and voter registration.

Latinx Voters: A Deep, Diverse Political Demographic

Chen said there are important regional differences to consider among Latinx voters, “the same way there are regional, and class-based, and education-based differences among white voters.”

“We talk about those different influences on white voters all the time, and yet the public tends to group Latinx and African American and minority voters in general as these sort of homogeneous groups, when in fact that’s not really what we see as support,” Chen said.

Alvarado described a wide range of issues that matter to Latinx voters.

“Yes, immigration tends to be a wedge issue, but it’s not usually the most important issue among Latinx voters,” he said.

Alvarado said that surveys he’s seen show the economy and jobs are a “huge part” of what gets Latino voters’ attention.

“They’re very, very tuned in on what’s happening with COVID now,” he said. “And the government, the spread of misinformation and hate. I think that’s something that many are looking at, especially the youth. Black Lives Matter, things like that, are galvanizing.”

When it comes to thinking about Latinx voters, Chen said it’s also important to think about “other competing identities, or intersecting identities,” like age.

Alvarado pointed out there are about one million Latinos and Latinas turning 18 and eligible to vote nationwide every year, including 2020. He said a quarter of Milwaukee Public Schools’ student body is Latinx, and nationwide, the median age of all native-born Latinos is 19.

“Over the next two decades, Latinos will be a very important part of making decisions on who are elected officials nation-wide. And Milwaukee is no exception,” said Alvarado.

Alvarado said reaching the youth in the city is a focus for groups like LULAC and the LWV. They’re in high schools registering young people to vote, and following up with texting and other messaging, he said.

Gerrymandering, Voter Registration Are Among The Political Barriers Latinos Face

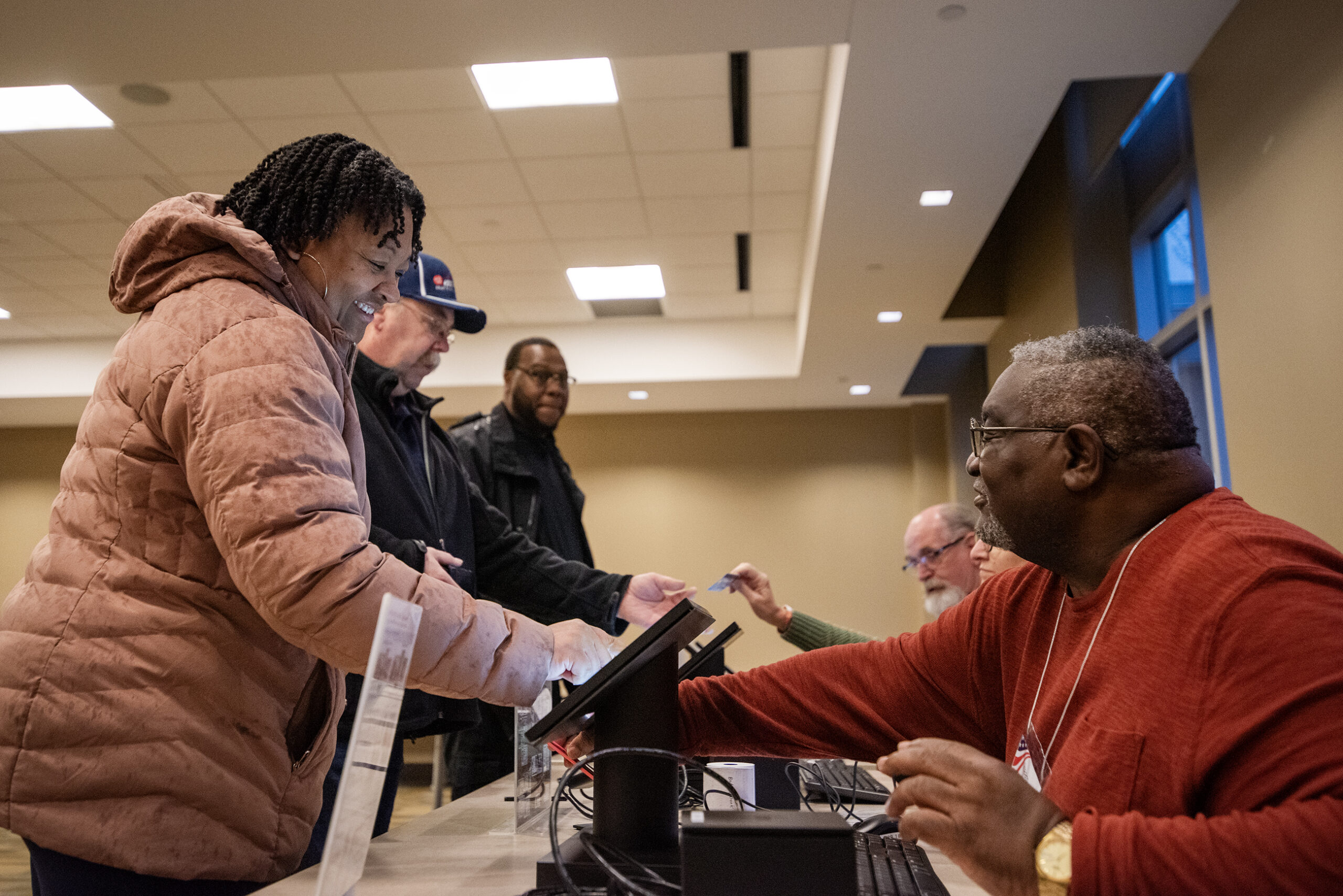

Alvarado said voter registration is one of the biggest challenges facing the Latinx community on Milwaukee’s near south side. He said LULAC has been working to register people for the past eight years in the neighborhood, specifically at a Department of Motor Vehicles location there.

Chen and Alvarado also brought up problems with gerrymandering, both nationally and in Wisconsin, to reduce the influence of minority communities by stuffing them into the same voting districts.

“Immigration status and racial minority status tends to correlate in this country with lower levels of mobility, income and education,” Chen said. “Yes, some of that’s changing, but it leads to different kinds of geographic restraints.”

Alvarado said he was part of an effort to redistrict Milwaukee. “Unfortunately, it’s partisan mapping now,” he said, referring to a “broken system we have in Wisconsin.”

“One party gets the majority of votes, but they get a lot less seats,” he said.

“There’s some real thorny issues that need to be overcome in the way districts are drawn,” Chen said, “as well as the way our social safety net is developed, in order to see a broader distribution of minority voters that isn’t so packed into certain states or Congressional districts.”

There’s also a political barrier at the national level for Latinos: geographic distribution. Chen cited a Pew Research study showing that more than 60 percent of naturalized citizens, including Latinx immigrants, live in just five states — California, New York, Florida, Texas and New Jersey. Of those, Florida is the only one seen as in play for the national election.

Alvarado confirmed both political parties are trying to court Latinx voters, although Chen said it’s typical to see around 60 to 65 percent of those voters favoring Democrats over Republicans.

That doesn’t mean the coalition won’t change, he added.

“It isn’t the same historical legacy (for African Americans) around say, the Civil Rights Act of the 1960s, or the way the Democratic Party has positioned itself with African American voters,” Chen said. “Democrats can’t necessarily count on this as a consistent voting bloc.”

To build support within either party, Chen said, it will take making an effort to connect with these communities and staying engaged on issues they care about, even during non-election years.

Gómez agreed: “It really has to be an ongoing kind of effort.”

That effort, Chen said, should also focus on young people.

“We should be thinking about the issues they care about, things like education, economy, having jobs available to young people,” Chen said. “These issues that are cutting across racial, demographic lines, in a way that will really drive home that point, that change that Eloisa is referring to in her question.”

This story came from an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it in a future story.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to clarify statistics on Latino voters, and survey findings on Latino voter issues.