“Saturday Night Live” is celebrating its 50th Anniversary this year. And although SNL is considered a cultural institution, creator Lorne Michaels has mostly avoided the spotlight.

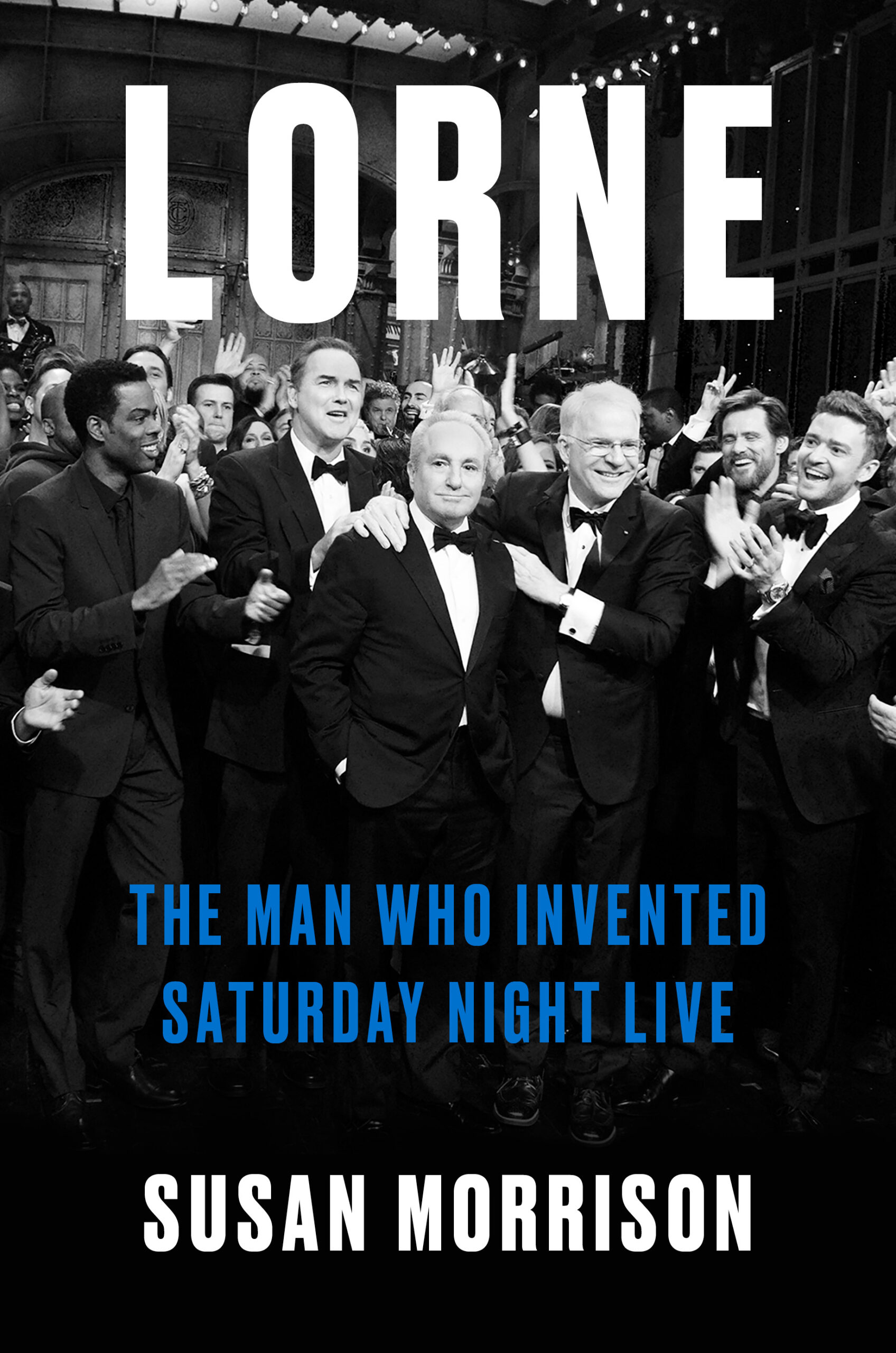

A new biography, “Lorne: The Man Who Invented Saturday Night Live” attempts to peel back the curtain on Michaels’ life and career by compiling hundreds of interviews with Lorne, his friends and SNL stars — including Will Ferrell, Tina Fey and Dan Aykroyd.

Susan Morrison is the book’s author and the longtime articles editor for The New Yorker. She recently talked with WPR’s “BETA” host Doug Gordon about interviewing Michaels, his start in television and the pressure cooker of SNL’s ambitious live format.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Susan Morrison: There’s really nobody who is more responsible for the way five generations of people have laughed and what people find funny. And I just thought that was such remarkable longevity.

I knew Lorne a little bit because I worked for him very briefly, but I spent an awful lot of time, years, talking to him and watching at his elbow as he put the show together. And I feel like I have a pretty good idea of how he manages creative people, what he thinks is funny, his appetite for having a variety of voices and kinds of humor. It was a rewarding experience, and I’m so grateful and amazed that he ended up giving me the access that he did.

Doug Gordon: How long did it take you to write the book?

SM: I’d say I reported the book for about five years. I took a long time because again, I was a novice at doing this. I’ve edited a lot of greats over the years, but doing it is another thing. And then three or four years writing it.

I originally wrote a manuscript twice as long as the one that you see now. Judd Apatow has been begging me for the director’s cut. It’s a lot of juicy stuff in there.

DG: Can you tell us a bit about your first interview with Lorne?

SM: I’ll tell you about the first two. I knew Lorne was a private person who generally avoids talking to the press. That’s worked for him all these decades. But I knew I had a real point of view on him. I’ve been hearing his people talk about him, exclaim about him, complain about him for years. So I went over to Lorne’s office. I just emailed him and said, “I’d like to come over and talk to you about something.” I said, “Listen, I just have signed a deal to write a book about you in the show. I don’t need anything from you. You know I’m connected in your world, but if you wanted to talk to me and participate, it would be a richer book and a better book and your legacy deserves this kind of a book.” And we talked in a very civilized way for a half an hour, I guess. And I could see he was taking it in. He wasn’t loving it [LAUGHS], but he was taking it in. And he said, “Let me think about it.”

And so, a few days later, I contacted him again and we met for a drink in a hotel bar and I thought what would happen then would be more negotiation about things. But really, we sat down in this hotel bar for a drink and I didn’t have a notepad or anything with me. But he just started talking and unspooling those fantastic Lorne Michaels stories about the old days and I realized, “Oh, OK. I guess this is a go.” So I ran into the bathroom and scribbled things down as I could remember them.

But, again, he’s such a classy guy. He didn’t put any constraints on me. We made no deal. He didn’t want to see anything. Nothing was off limits. And then I just started emailing his assistant and I would go over there a couple of Friday nights a month and we’d spend an hour talking. And it just went like that for a few years. And that’s how it happened.

DG: Lorne’s father, Henry Lipowitz, died of a pulmonary embolism at the age of 50 in 1959. This was just shortly after Lorne’s bar mitzvah. What impact did the death of his father have on Lorne?

SM: I think it was cataclysmic. He loved his father. And making it even more painful, Lorne had had an argument with his father the night that he collapsed and never got to see him again or talk to him. So he carried around this feeling of guilt and bewilderment for decades. And it’s made him completely non-confrontational in terms of his dealings with colleagues and underlings. He doesn’t yell. He doesn’t get into fights.

And it’s interesting, Lorne knew Frank Shuster of Wayne and Shuster early because he became friends with Rosie Shuster, who he would later marry. And Frank Shuster was a real father figure to him, too. He lived a few blocks away. Lorne spent a lot of time there being mentored and taught about the basics of comedy. Lorne always admired Wayne and Shuster, who were huge stars. But they never left Toronto and went to LA. And as Lorne put it, they resisted the Canadian dream, which was to be not working in Canada [LAUGHS]. And I think he admired that. For a time he thought, “I want to do that, too. I want to make it,” but stay in Canada and rebuild his own family in Canada. And he had some success there doing a variety show with Hart Pomerantz on the CBC. And even though it was a success, the CBC pulled a plug.

“The audience would be seeing it at the same time the network would be seeing it. And he would have a really unusual amount of freedom.”

Susan Morrison

So he realized he had to have a bigger horizon. So then he went to LA where he knocked around for 10 years on pretty crummy middle-of-the-road variety shows and almost gave up on television altogether because unlike the movies and music, which were really blending into the counterculture, television at that time was kind of stuck in the 1950s.

He had this idea of updating the variety show format with, as he would put it, what was happening in the streets. Sex and drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. He pitched that show for years on deaf ears.

And the only taker he finally found was NBC, who in 1975 was looking to put a show on at 11:30 p.m. in late night broadcast out of its New York City headquarters in Rockefeller Center. What he later realized is that it didn’t even really have to do with the strength or the content of the pitch. It had to do with the fact that he was solving a problem for NBC because Johnny Carson, the network star and biggest moneymaker, wanted his reruns off the air.

What’s interesting is that, at first, Lorne was thrown by the idea of it being live. He had never considered doing live TV. But he quickly realized that there was a real upside to it. Because if you’re going live, it means you’re not going to do a pilot. And if you don’t do a pilot, that means no 50-year-old network guys are going to tell you what’s wrong with it and give you notes. The audience would be seeing it at the same time the network would be seeing it. And he would have a really unusual amount of freedom.

DG: The debut episode was broadcast on Oct. 11, 1975. George Carlin was the host, Billy Preston and Janis Ian were the musical guests. How did viewers and critics react?

SM: Well, critics were pretty lukewarm. They thought that it was pretty ragtag.

The first sketch — the famous Wolverine sketch — Belushi plays an immigrant learning English and then falls over dead once his instructor falls over dead, and Belushi thinks he’s supposed to repeat what the instructor is doing. That was funny and weird and Chevy Chase came out at the end of it dressed as the stage manager and yells, “Live from New York, it’s Saturday Night!” I mean, that sketch signaled a lot of what the show would be. Breaking the fourth wall, death obsessed.

The show itself was pretty rocky, and a lot of viewers called in and complained. George Carlin’s monologue had made fun of religion. Catholics hated it. Some of the bigger NBC executives thought that it was sacrilegious and were very upset. Herb Schlosser, NBC’s president, was perfectly happy with it, and he was willing to give it time. But some people at home thought, “This is kind of a mess, but it’s really interesting. I’m going to watch next week.”

Steve Martin, who was an up-and-coming stand-up comic, watched it in Aspen where he was on tour. And he was blown away. He just said, “Oh my God, they got there first. They captured the zeitgeist.” He felt that’s what he was trying to do.

So it was a mixed reaction. In this day and age, it might’ve been canceled right away, but then they just kept it on. And I’d say Lorne thought that by the fifth or sixth show with Candice Bergen hosting, it was working.

DG: Lorne left the show in 1980 saying that he was burnt out, and NBC appointed a new producer to take over SNL, the talent coordinator, Jean Doumanian. How did Lorne react when he found out about this?

SM: He was shocked that they were not bringing him back, that they were going to put his show on the air without him, and that Jean Doumanian, who was one of his own people, hadn’t told him that there was a lot of back-channel negotiation.

There are so many times along the way in his 50-year journey where he talks about innocence being lost, and that was one of them where he really got the full measure of how Hollywood worked. And it was painful for him.

DG: Yeah I can imagine it would be. What made Lorne decide to come back to SNL?

SM: After the first five years when he was burnt out, he thought, “OK, that was my television period. Now I’m going to enter my Mike Nichols period.” Ever since he had seen “The Graduate,” he knew he wanted to direct feature films. He loved Hollywood. His grandparents ran a movie theater. He was steeped in movies his whole life. So he thought, “It’s time to go to Hollywood and make movies.” But none of this really worked out. It just turned out not to be his strong suit.

So NBC said, “We’d really like you to come back, and if you don’t come back, we’re going to take the show off the air.” And at that point, he again thought, “Well, this is my baby. I created this thing. I’d really like to see it flourish.” And I don’t think he’s ever regretted it.

DG: Both Bill Hader and my fellow Canadian, Mark McKinney, had panic attacks while working on SNL. Can you tell us about their experiences?

SM: I think panic attacks are a pretty common experience on that show. The longtime head writer, Jim Downey says, “If you were to meet with a group of Swiss engineers and give them a list of all the things you needed to get done to produce an episode of SNL, they would look at it and say, “You probably need 13 days to do that.” But at SNL, you have six days. It’s an enormously high pressure atmosphere.

I sometimes compare it to “The Hunger Games.” At Wednesday read-through, there’s four hours worth of comedy sketches. By Saturday night, it’s gonna be whittled down to seven or eight sketches. So it’s just this constant cutting and winnowing and shortening.

All week, these people are trying their best. They’re not sleeping. They’re working hard because they want their material on the air. They want to be on the air.

Seth Meyers told me the worst thing that can happen to you on a Saturday night as a cast member is to not even need hair and makeup. And that sometimes happens. You find out at 11 o’clock, everything you’re in has gone in the toilet and you have nothing to do. So, a lot of them just learn how to handle it better over the years. I know Hader did and Mark did. But everyone compares it to jumping out of an airplane.

As Steve Martin once put it, “On live television, anything that goes wrong stays wrong.” It’s a pressure cooker. I think Lorne has figured out a way to use that adrenaline, and the high wire knife point aspect of it definitely gives the show some extra juice. But people pay a price.

DG: As you point out, Lorne often says no one ever leaves show business. Lorne is 80 years old now. When do you think he will call it a career?

SM He loves the show so much, and even though he likes to say that if you’re good at producing, you leave no fingerprints, his fingerprints are quietly on every aspect of it. His personality infuses the vibe, the glamor, the hard work, the excitement. I just don’t imagine him ever walking away from it. I think they’d have to take him out of there on a stretcher.