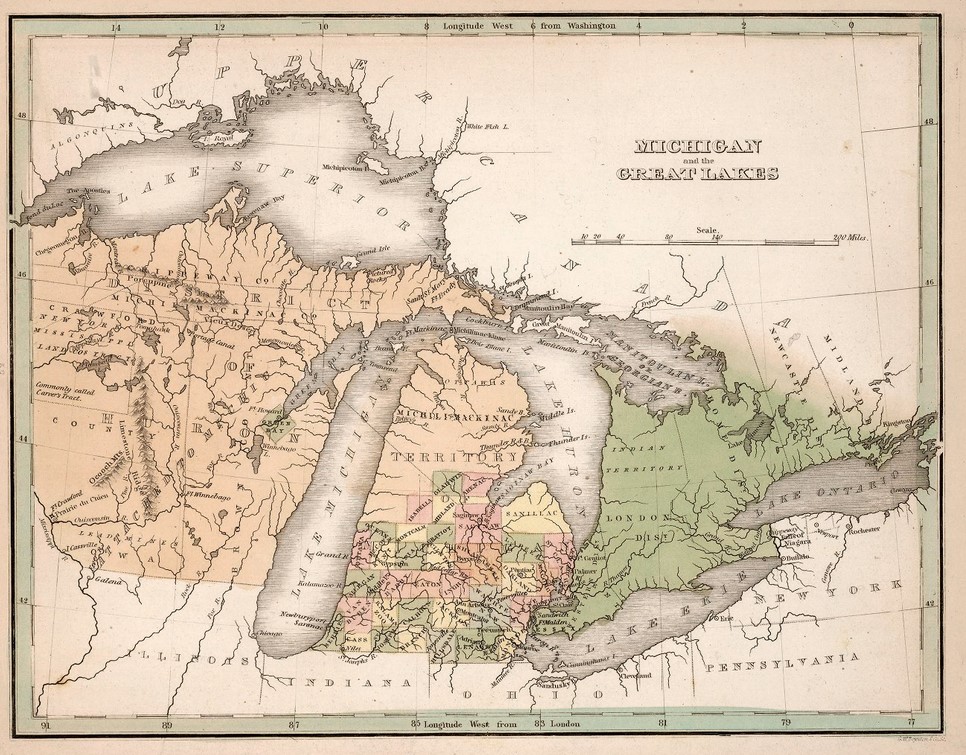

If you look at a map of Wisconsin, you’ll notice the state is full of communities with French names.

Portage, Racine, Prairie du Sac, Radisson, Butte des Morts — the list goes on.

In fact, Wisconsin used to be pronounced “Ouisconsin.” Which, to be clear, does not translate to “Yes, ‘Sconsin!” This is the French misinterpretation of “Meskousing,” (sometimes spelled “Meskonsing”), an Algonquian word for the Wisconsin River.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

How Wisconsin got its name is complicated, and comes from many mistranslations and mistakes. But that’s a whole other story.

With all those French names, a listener named Jan reached out to WHYsconsin because they were wondering why we can’t seem to say all those French names on the map right.

“I am so amazed that so many people in Wisconsin mispronounce the French names of places, such as Prairie du Chien and Fond du Lac. Why?” Jan wrote to WHYsconsin.

The sound of those rhotic American “r”s in “Marquette” and “Presque Isle” might be grating to French speakers. But according to University of Wisconsin-Madison linguistics professor Joe Salmons, the Wisconsin way of pronouncing these names is not actually wrong. It’s just … different.

As any descriptive linguist worth their weight in salt will tell you, there’s actually no “right” or “wrong” way to say things.

“There are established ways,” Salmons said. “(The Wisconsin pronunciations) are not wrong; they’re established local norms, and those local norms change over time.”

Still — though saying this might make descriptivists angry — as Jan mentioned in their question, the French pronunciations are technically correct.

So how did we go from “por-TAHJ” to “PORT-uhj,” from “lah-PWAHT” to “leh-POINT?” In other words, how does the “wrong” pronunciation become the “right” one?

Listen to a French speaker pronounce some Wisconsin communities with French names.

“The general issue is how you integrate any words from other languages into a new language,” Salmons explained. “Most Americans can’t pronounce the (French) nasalized vowel at the end of ‘Chien’ or the (German) consonant at the end of a name like ‘Bach.’ So we adjust. We have to substitute sounds.”

And that’s when new pronunciations are born.

Pronunciations change over time and are influenced by the cultural context. Often, the pronunciation becomes a hybrid of the original and new languages. Salmons gave a personal example involving the word “taco.”

When his wife, who is from the upper Midwest, moved to California in the ’70s, she learned more about the Latinx culture and cuisine. During a visit home, a relative invited her over for “TACK-ohs,” Salmon said. The pronunciation of the word was inaccurate, but commonplace at the time in the Midwest.

As the Latinx culture and cuisine has grown across the United States, the American pronunciation of the word has settled into a blend of Spanish and American English: “TAH-coh.”

“Early on, (when) that was a relatively new food item, a lot of people used a heavily Anglicized pronunciation,” Salmon said. “But we’ve now shifted back to something that’s a little more Spanish. We don’t say it like a Spanish speaker — our ‘t’ is very different from a Spanish ‘t’ — but we’ve now changed that vowel to be much more Spanish-like.”

This is what happened with French names in Wisconsin.

Over hundreds of years, the French pronunciations fell by the wayside. And in the process, some of those names have acquired French flairs. For example, in “Butte des Morts,” we pronounce “Morts” in a French-y way, without the ‘s’ you would usually have in English.

Listen to a French speaker pronounce “Butte des Morts.”

‘I looked at the Wisconsin map, and I saw all these French names’

But why does Wisconsin have so many French place names to begin with? That’s a question Tomás Dominguez, from Mukwonago, had. He asked WHYsconsin: “With all the French history and French names in the state, why isn’t there a stronger French culture?”

Gabrielle Verdier, a professor emerita of French at UW-Milwaukee, wondered that, too.

“(That’s) exactly the question I had when I came to Wisconsin in 1993,” Verdier said. “I looked at the Wisconsin map, and I saw all these French names.”

But French culture? Not so much.

As Dominguez wondered: “I know that, at least in Milwaukee, there’s at least one major university named after a French explorer, Marquette University. The history of the French exploring the Wisconsin territories is rather well documented. Nowadays, we think of a lot of German culture in Wisconsin, especially with all the beer brewers in the state. But… Why didn’t the French stick around?”

But French-speaking immigrants did stick around. There just weren’t that many of them to begin with.

From 1820 to 1950, fewer than 19,000 French immigrants came to Wisconsin. French-speaking migration to Wisconsin was paltry in previous centuries, as well, for a variety of reasons.

The first French-speakers to come to Wisconsin were interpreters Etienne Brule and Jean Nicolet, who came from New France in the early 17th century in search of a route to the Pacific Ocean. A few decades after the explorers, fur traders brought their lucrative trade to Wisconsin

Back then, New France encompassed parts of what we now know as Canada and a large swath of the modern-day Midwestern U.S. The settlement of Quebec was established in 1608.

But, as Verdier explained, “It was hard to get the French to move to the New World because it was really cold here.”

And compared to the rest of Europe in the 17th century, “Life was not that bad in France. France had the biggest agriculture of any European country. So there weren’t as many famines. There wasn’t as much starvation as in, for example, Spain, or in England and Ireland. So (French) people were not necessarily moving to the New World for economic reasons,” she said.

That explains why, according to Census data, only 2.9 percent of Wisconsinites have French ancestry, compared to a whopping 36.8 percent with a German ancestry.

And those early French-Canadian explorers who did come to Wisconsin had a penchant for naming things.

“All of the French names came from the fact that French-speaking people were the first to arrive in that territory — which belonged to, of course, Indigenous people — and (they) gave these territories French names,” Verdier said.

The French adapted some Native names and threw in some names of their own. Then they put them on maps, and they stuck.

Although not many French-Canadian settlers made their way to present-day Wisconsin, they contributed a lot to the territory’s economy with the fur and lumber trades, as well as mining in northern Wisconsin.

So, French culture isn’t shot through contemporary Wisconsin in the way that, say, German culture is. If it were, we would have a boulangerie on every corner. But those early explorers’ impact on Wisconsin — even 400-ish years later — well, it’s énorme.

This story was inspired by an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.