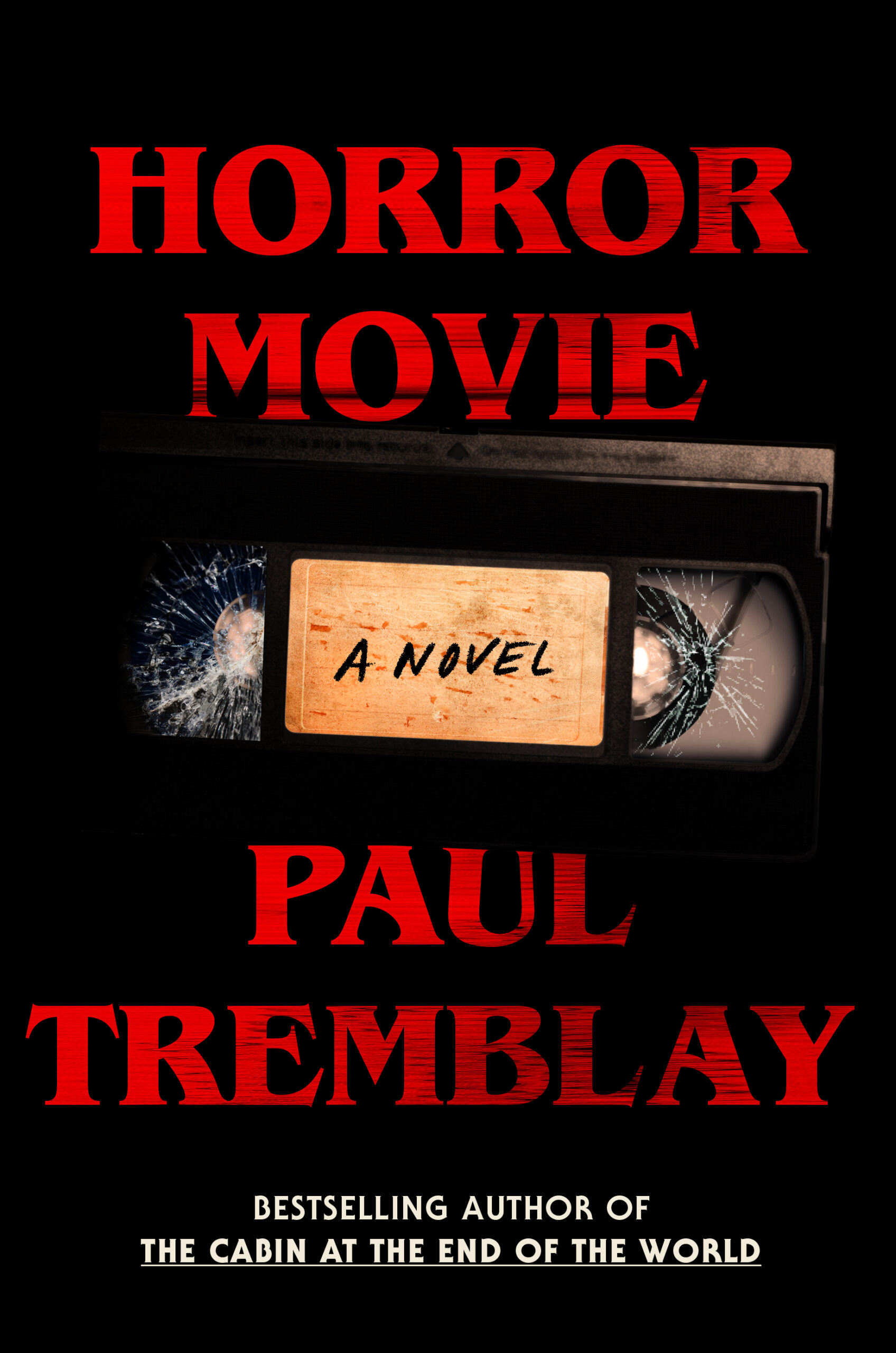

Paul Tremblay is an award-winning author of literary horror fiction. He has received the Bram Stoker, British Fantasy and Massachusetts Book Awards.

Tremblay is going to need a bigger trophy room.

M. Night Shyamalan adapted Tremblay’s 2018 horror novel, “The Cabin at the End of the World,” into the 2023 movie, “Knock at the Cabin.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Tremblay’s latest novel is “Horror Movie.” It’s about a group of young guerilla filmmakers who create an art-house horror movie, and release only three of the film’s scenes to the public.

The horror movie develops a very large cult following, and 30 years later, Hollywood is chomping at the bit to make a big-budget reboot.

The only surviving cast member of the movie is the man who played the character known as “The Thin Kid.” Now 50 years old, he is haunted by the memories of making the film — eerie events that happened during the making of the film and the resulting tragedy.

Tremblay discusses his relationship with horror and suspense with WPR’s “BETA.”

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: Paul, you have a master’s degree in mathematics. Have you been able to use your math skills when you’re writing horror fiction?

Paul Tremblay: The short answer is I’m not sure. Maybe I approach writing more analytically or math brain than others. Also, I think that’s me maybe just trying to find an answer to the unanswerable.

DG: Very well said. What inspired you to write “Horror Movie?”

PT: It was a funny accident for me. I was sort of fishing around for a novel idea, and friend and writer Stephen Graham Jones, an amazing writer and even better friend, recommended I watch film critic Walter Chaw.

During the pandemic, Walter was hosting weekend matinees online and at the Denver Public Library. And after the movie, he would host a discussion with the filmmaker or someone really cool.

The first one I watched was Walter and John Darnielle discussing “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,” and it was just such a fun discussion. It sort of sent me into a little bit of a rabbit hole of rewatching the movie and reading about it and reading about how dangerous the set was.

DG: We’ve had Stephen, Walter and John on the show, so I was very eager to watch the video. And it is great. Those guys are such good talkers and really analytical. You mentioned a rabbit hole, but you’ve also said it sent you into a chainsaw wormhole. How so?

PT: When I first discovered horror as a child, it was Godzilla movies, black and white movies. And besides giant monsters, I tended to gravitate towards more of the spooky, supernatural, psychological. And the really gory stuff I couldn’t handle. It was just too scary for me.

So “Texas Chainsaw” was a movie that I avoided watching until probably like my 30s, just partly because of its reputation. And then when I saw it, I understood. Wow, this really isn’t that gory. Certainly it’s not as gory as the culture imagines it is. And it’s just this powerful, feral, really interesting movie. And I wanted to try to capture some of that tone and also interrogate my own experience with horror since, like for the first two decades of my life, my experience with horror was almost exclusively movies.

And then I fell into reading much later in life compared to most writers in my 20s. So now that I’m 50 and I’ve spent like 30 years really in a 30-year crash course on reading and writing, I wanted to flip it and see the differences between a horror story book and a horror story film, and try to maybe squeeze both aspects into the book at the same time.

DG: I love the way you structured “Horror Movie” — bouncing between your wonderful prose, and then the screenplay for the film. Plus you’re playing with tense a lot. How did you pull that off?

PT: Thank you. Some of it was like I wanted to feel like a little bit freewheeling. I didn’t create an outline before I started writing. I just dove into it.

I kept a lot of notes as I went and really, at the time, a lot of it was just by feels, like, OK, I have this scene set in the past on the set while they’re filming. And then, OK, here comes the next section of the screenplay. Then here comes a jump into the future.

And I just sort of trust the whole subconscious thing. And at the end, I tried to make sure everything fit together. It was like an in-the-moment of writing decision for the most part.

DG: One of the most powerful scenes is when you keep the reader waiting for a jump scare, and it is a very long wait, like “Waiting for Godot” long. Can you walk us through your creative process for this scene?

PT: I’m probably going to butcher the quote, but I think Hitchcock used to talk about how suspense was knowing there was a bomb under the table — the thrill was actually going off, but the suspense was knowing it was there. And it’s going to blow up in any moment.

Most of my books tend to have a reference to something that we know is going to happen at about the two-thirds point. And the whole idea is to build up to that sort of moment. And then it’s not really a climax. But to me, the aftermath is the scary part, like, what are the people going to do now that this thing has been revealed?

So to try to do that as a specific scene in a movie, which was the scene in the screenplay where there is sort of the big wait. And if a movie were to do something like that, I think that would be where you get to activate the viewer’s brain, because they’re going to imagine what’s coming, you know?

And that happens so many times and some of my favorite movies, and it’s not like a big, fat long scene. I’m thinking of a movie like “Lake Mungo”. There’s a scene where the whole movie builds up to a reveal of what was on this character’s missing cell phone and watching that scene. Even though it probably only lasts three or four seconds, it felt to me like it was five minutes, if not longer, just because I was so terrified by what was coming to me.

Writing that scene was like, this is why I like horror movies, why they’re fun. And maybe, hopefully, the reader feels the same way or or has some similar thoughts.