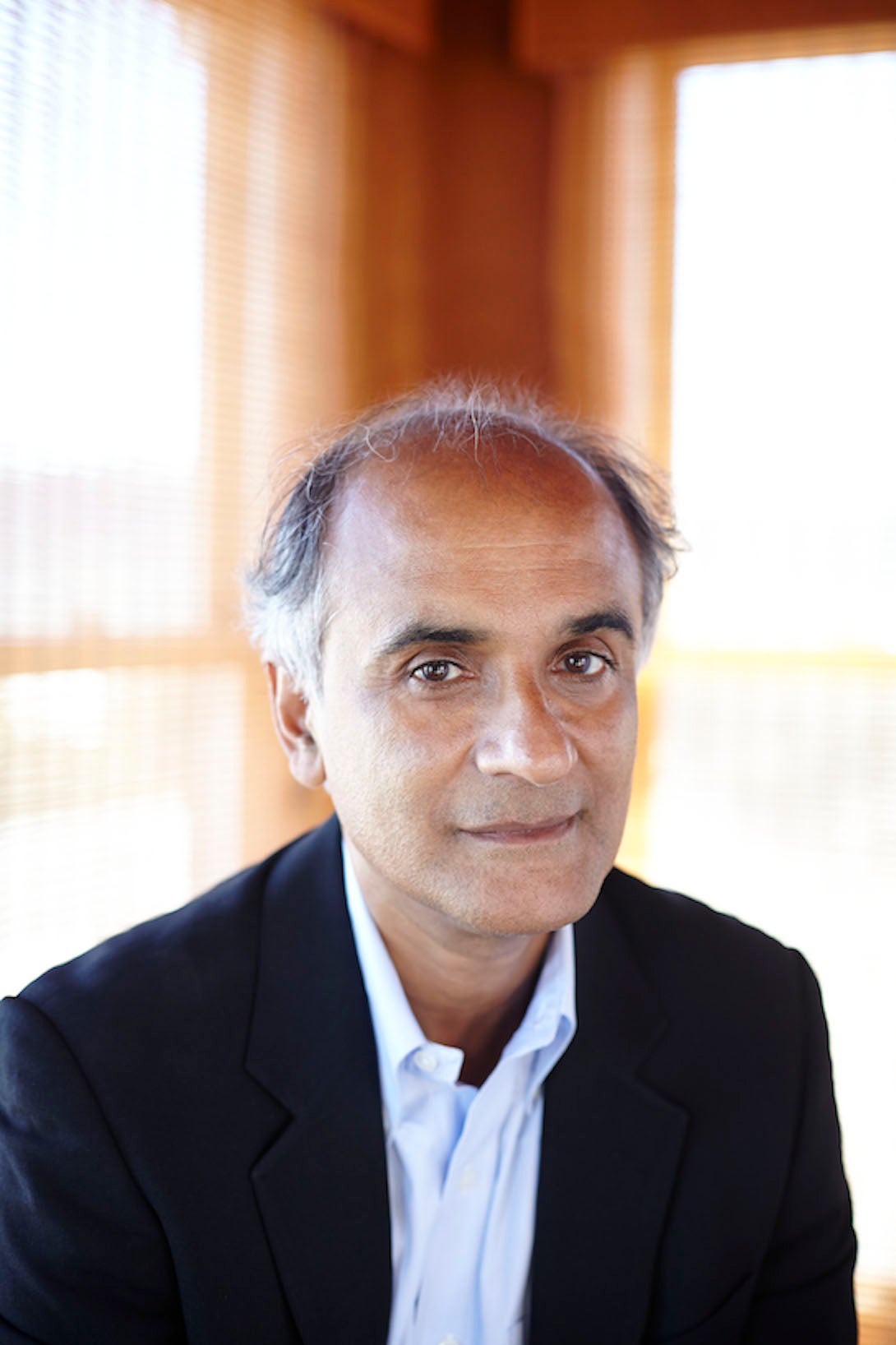

After losing his California home to a wildfire in 1990, writer Pico Iyer went on his first retreat to a Benedictine Hermitage in Big Sur, California. He’s since made more than 100 retreats to the monastery over three decades.

In his new memoir, “Aflame: Learning From Silence,” Iyer reflects on how spending time in quiet retreat saves him from the noise and distractions of the everyday world and brings him joy. He says it’s something we can all do, even if it’s through a walk by ourselves.

Iyer tells Shannon Henry Kleiber of “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” how retreats brought him out of his mind and “into his senses.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

Shannon Henry Kleiber: What keeps bringing you back to this — now you call it — a second home?

Pico Iyer: Yes. I think of it as my secret, deepest home. And the simple answer might be liberation. All these hundred retreats later, I still find that every time I’m driving along the narrow road to the hermitage, there are a thousand reasons not to go. I’m fretting about leaving my aging mother behind, and I’m worried about my deadlines. My bosses can’t get hold of me for 72 hours because there’s no cell phone reception or internet there. And then I step out into that silence, and all of that is gone. And I’m just released to the beauty around me. It’s as if little Pico and all his plans and fretful thoughts are left down on the highway.

And of course, over these hundred retreats, much has changed in my understanding of the monastery and what I get out of the silence. Sometimes I’ve been there when suddenly torrential winter storms have erupted and the rain patters on the roof all night and I can’t see a single light across the hillside. And it can be scary. It’s really like 40 days and 40 nights in the wilderness.

But essentially, every time I go there, I remember what I really love, whom I really love. And I also remember what I should be doing with my life. And I find that, as with most people, I think my regular day is so cut up and caught up with a thousand distractions. And I’m going from the pharmacy to the bank to the supermarket. I never really can have perspective and see what’s important, and I never can step back really to think, what should I be doing and what is the most important thing to me?

I think it’s interesting, during the pandemic, when all of us had an enforced retreat in lockdown, many of us suddenly began to remember, this is what I care about — my family, my friends. This useful, compassionate pursuit. And so much of the news and other things that distract us really fall away.

SHK: It seems like a practice that comes back to you.

PI: Yes, I think a practice is a beautiful way to put it. I’ve never meditated. I don’t have a yoga practice. And really, I don’t do anything religious when I’m on retreats. These are solitary, unguided retreats. So I just I take walks. I read books. I write a lot of letters to friends at night. I just look up at the stars. Often I do nothing at all, which is exactly what I don’t allow myself to do the rest of the time. But I think it is my equivalent to the kind of practices that people maintain, whether it’s a running practice or a swimming practice or a meditation practice.

And the other thing that has always hit me from the first day I arrived is that I should stress I’m not a Christian. And yet the Benedictine monks who take me and 15 other retreats at a time are so open-hearted they know that belief is much less important than something unnamable within. And I think they have confidence that whoever goes will find whatever she needs or whatever is most sustaining to her. So there’s no insistence on reading certain texts or attending to services. They just have this beautiful faith that divinity will come to us or what we need will come to us in any form.

“The surprise was to realize that being alone was only a gateway to learning how to be better with other people.”

Pico Iyer

SHK: I was so interested to hear that it was a Catholic hermitage. I grew up Catholic and I used to go on retreats when I was younger, and I did love them in many ways. They were an opportunity to be with people and then be alone. And I’m an only child. I know you’re an only child. And I did love this opportunity to be alone. So I was wondering how you see being alone and loneliness as different when you’re on this retreat.

PI: You’re absolutely right. I’m an only child and I’ve chosen to be a writer, which means I spend eight hours a day alone at my desk. So I love being alone. And I think being alone is the opposite of loneliness. I’m one of those people who only feels lonely in a crowd. I could feel lonely at a cocktail party and I would never feel lonely if I’m just by myself walking down the street or left to amuse myself.

So as soon as I came to this beautifully solitary place with the most radiant view of the most sparkling coastline I’ve ever seen, of course I was in heaven. But I think to me, the surprise was to realize that being alone was only a gateway to learning how to be better with other people. And of course, the monks in their enclosure are the opposite of alone. They’re spending all that time tending to guests like myself and looking after one another, and so in some sense I was never alone. I felt companions like birdsong in my garden and the animals going across that fence, which otherwise I would never notice.

And then the other beautiful surprise was that when I would take a walk along the monastery road, I would sometimes pass one of the other people staying there. And if we stopped to talk for two or three minutes, I think we would instantly feel like deepest friends. Anyone I met there I would trust because at some level, they were coming there really for the same reason as I was — in search of silence, in search of something they’d lost or misplaced inside themselves, in search of whatever beauty they have within them.

SHK: It sounds like even though it’s not about religion, it is in some ways about spirituality. How does being on retreat at the hermitage deepen your spiritual life?

PI: T.S. Eliot asked, “Where is the life we have lost in living?” And I think most of us — especially as our life and our world gets ever more fast and furious — have this sense that there’s some deeper part of our lives and deeper self that is getting forgotten in the rush. And I feel that’s what I recover there. So in some ways, it’s almost like being freed from myself and opened up to some much larger self. I feel much more a part of some bigger whole, which makes me much less scared of things like death. And it also makes me reorient myself and think very differently about what is success and what is joy.

So when I first went there, I was an essayist for Time magazine and I had quite an exciting job. And I was leading something like the life I might have dreamed of as a little boy. Doing that made me think, “Is that really where your fulfillment comes? Or might your fulfillment not come from looking after a family and living much more quietly and enjoying some kind of radiance every day instead of running from activity to activity?”

And one of the things that I learned soon after I arrived from the writing of the monks is just that notion that joy is the happiness that doesn’t depend on circumstance. In other words, joy is something that you create within. So even in difficult times, which all of us are going to have to endure and face, there’s some strength and confidence there that it’s not the end of the world and that there’s some reality larger than this that will sustain you. But the more the world speeds up and the more information is flooding in on us, I think the more some of us feel this longing to escape from that.

SHK: There’s so much noise now, so many distractions. The news, technology, everything that is being thrown at us. I do think of these distractions as not allowing you to think about other things. And as you’re talking, I’m thinking about Pico Iyer as these two different people — one in the real world and one in this wonderful hermitage world, which is of course a real world, too. How do you come back to your day to day world and merge those two selves?

PI: Such a good question, Shannon. Going there tells me what is real and reminds me that what I see as the real world when I’m caught up in the middle of it may not be the whole story and maybe just the performance, as it were. But you’re absolutely right, if you’re guessing that. Every time I return from a three-day retreat for about one day, I’m walking on clouds and I’m radiating joy at everyone I meet. And within three days, I’m back fretting about my income tax return. And why has my editor not got back to me? So the spell doesn’t last very long, but I think some residue remains.

And as I’m back in my regular life, some part of me knows, don’t take this too seriously. There’s something much deeper that is part of every life and that you can’t afford to forget. And it almost puts a frame around my daily life so that I can see everything that’s around it, which is much more significant.

I remember soon after I began going there, a very kind friend said to me, “Isn’t it selfish to leave your loved ones behind and leave all your responsibilities behind for three days or sometimes two weeks?” And I said to her, “I think it’s actually the only way I can be a little less selfish.” So as I worry about leaving my aging mother behind whenever I go there, as soon as I arrive, I realize it’s only by going there I’ll have anything really joyful and fresh and exciting to share with my mother. And of course, in the space of three days, she hasn’t really missed me. She can get on perfectly well without me. And she is so delighted that the person who comes back through her front door is is so much more the son she wishes she would always see. Not distracted, not saying catch you later, not racing off downstairs to take care of the next thing on his to do list.

I sometimes think it’s almost like knowing there’s medicine nearby and as the world gets very difficult and we all go through innumerable challenges, just knowing there’s a sanctuary and an almost kind of answer to many of my problems not far away puts everything in perspective.

“We all have to make a living, but we also have to make a life.”

Pico Iyer

SHK: You were finding joy, and sometimes we don’t allow ourselves to have time for it or think we deserve it, but it’s vital to have joy in our lives.

PI: Yes. Because unless we do, we can’t really do justice to anything else. We’re not a great blessing to our friends and family and colleagues, and least of all to ourselves, too. I’m well aware that I’m a very fortunate person to be able to afford the time and the money to take three days off. But apart from being an indulgence, it seems to me the best and most important investment I can make.

My question for myself always is: What can I bring to the ICU? All of us at many times in our lives are suddenly going to have to walk into a very difficult life-and-death situation involving ourselves or other people and what is going to help us in that situation.

So over the time that I’ve been on retreat, my 13-year-old daughter was diagnosed with cancer. My mother was widowed. All kinds of things were happening. And I remember once I was sitting here in this apartment and I got a call in the middle of the night telling me that my mother had just been rushed into the hospital in California after a major stroke. So I flew back and I had to spend 35 days with her in the ICU as she was wavering between life and death. And as I was sitting by her bedside, I thought, really, my bank account isn’t a huge help in this situation. And all the books I’ve written and all the things I’ve accumulated on my resumé are totally beside the point. The only thing I could bring to my mother and the only thing that I could think to myself in that difficult situation was probably such clarity and calm as I had gathered mostly by being quiet or especially by being silent. And all the time I’d spent rushing around again would be no help in that situation. It was just the moments when I’ve touched something deeper than my regular life and I’ve had the sense of the larger picture that would be able to help me and would be able to help my mother.

And since every one of us is pretty much guaranteed to go through such moments more than once, I think that invisible savings account is really one that needs to be attended to. We all have to make a living, but we also have to make a life. And it’s that life and it’s that secret deposit that’s all that we have to draw upon when reality makes a house call.

SHK: Do you think that retreat and silence and working on your inner life is preparing you for your own death?

PI: Absolutely. And I think once you see something that doesn’t seem constantly to change, it makes you much less scared of change and of death. And of course, every time I go on retreat to that same hermitage, it’s a little different. And the people who are living there are coming and going. And the sea isn’t quite the same sea that I looked at three months ago.

But by and large, it represents relative permanence in a world of constant flux. By comparison, my daily life, where everything is moving all the time, it represents a kind of stability. And therefore, I remember actually when my father died and it was a very busy time because I was looking after my mother and taking care of all the practical arrangements. I realized the only way I could meet that situation was by driving one morning for hours up to the same hermitage, just sitting on a bench overlooking the sea for two hours, listening to the bells, hearing the birds looking at the ocean that never seemed to move and then drive four hours back. And somehow seeing that vision of permanence really helped me to deal with the impermanence of everyday life.

I suppose I haven’t thought of this before, but this is a long-winded way of saying that going on retreat teaches me what’s essential and then trains me to prepare myself for what is the essential stuff of life — such as death, which otherwise I would always tell myself I don’t have time to think about in my regular life until suddenly it comes upon me and ambushes me with some sudden drama.

SHK: Wow. Your book is called “Aflame,” and fire plays such an important part in your life, especially the burning of your family’s home. What does fire have to do with silence and how you create your inner life?

PI: I think silence is where we really kindle and keep burning the most important part of ourselves within, whether it’s devotion or concern or conscience. Not long ago I read that Carl Jung said at one point, “The difference between a good life and a bad life is measured by how we walk through the fire.” And insofar as we’re living in a world on fire and the house on fire, I think there’s an ever more literal truth to that. How do we keep hope alive when there’s so much natural disaster that strips us of all hope? We’ve never known as many extreme climate events as are now happening in every corner of the world in every form.

And yet, in the face of wildfires and tsunamis and hurricanes and flash floods, we can’t afford to let some flame die within us. The best thing we can share with our friends is an understood, shared silence. Any pair of lovers notices they share something when no words are exchanged that is far deeper than anything they could share in conversation.