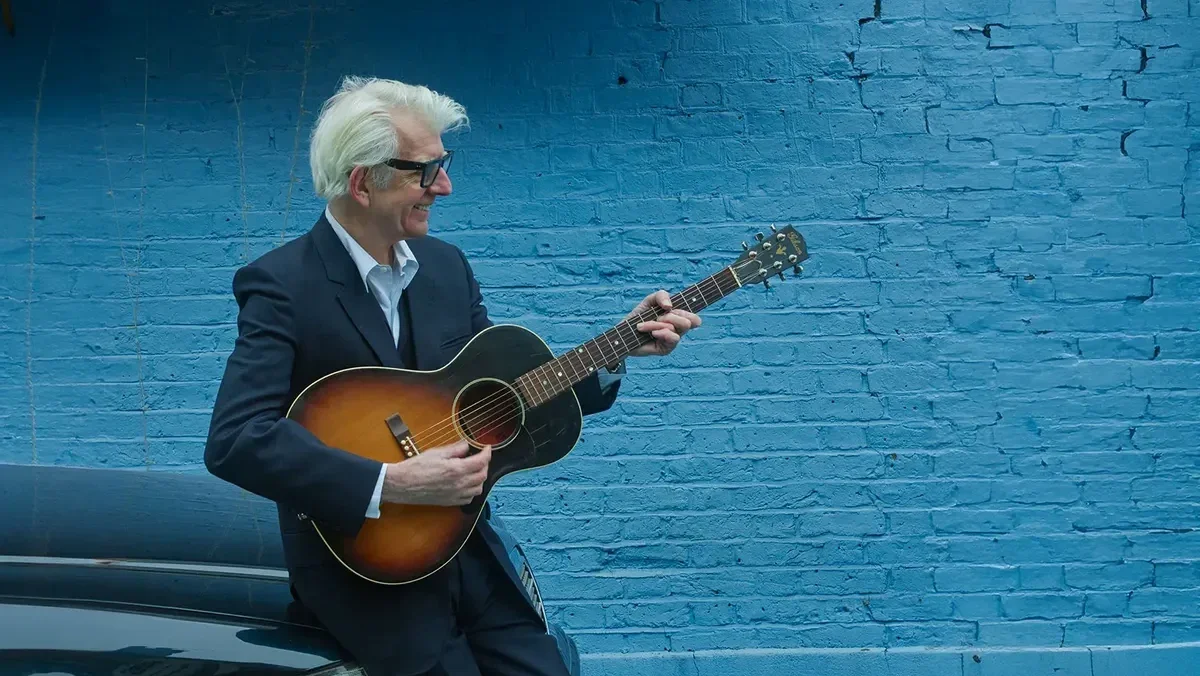

Peter Ames Carlin is a journalist and critic. His latest book is “The Name of This Band is R.E.M.: A Biography.”

In a time when many thought rock and rollers couldn’t come up with anything new to add to the genre, Carlin says Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills and Bill Berry did just that and pulled it off in a way that few other bands could.

WPR’s “BETA” sat down with Carlin to discuss R.E.M. and how the band found its unique sound.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: Peter, how did Stipe, Mills, Buck and Berry join forces to create R.E.M.?

Peter Ames Carlin: They met each other in Athens, Georgia. Three out of the four of them were students at the university in Georgia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Peter Buck, who had dropped out of Emory University in Atlanta, worked in the Wuxtry Records store.

Bill and Mike had gone to high school together in Macon, so they knew each other as teenagers and came to the University of Georgia together. Michael met Peter at Wuxtry, and they started talking about weird punk records and indie stuff they loved. They had so much in common.

They started making music together, and a mutual friend of the four of them introduced Mike and Bill to Michael and Peter and suggested they would maybe hit it off musically. They began to rehearse together, and three or four months later, they had enough material to play at a friend’s birthday party.

DG: I’d like to get your take on one of my favorite passages in your book. It stuck with me: “And the whole point of art, at least the way it was taught, practiced, and admired in Athens, was to be only like yourself, to describe the world the way you saw it, felt it, and tasted it.” Could you elaborate on how that applies to R.E.M.?

PAC: If we look back 40 years to the early 1980s, the overarching influence of pop music was on MTV and commercial radio. This moment of absolute esthetic conformity was coming because so much music was channeled through corporate gatekeepers.

So bands like independent bands and punk or post-punk bands, particularly R.E.M., were playing in opposition to that idea. And so, instead of trying to channel some sort of popularly held notion of what rock and roll should be and what songs should sound like, they were determined to be completely different in every conceivable way, shape and form.

I think the first line in the book in the prologue is, “Even from the beginning, you would know them by their refusals,” and there’s this litany of all the things in the course of their career that were standard for other artists to do that they would have nothing to do with. This idea of expressing something so deep within became their guiding impulse.

DG: As you’ve touched on, they had their own sound. And that, in my opinion, is half, maybe three-quarters of the battle, to stand out when you’re a new band by having your own sound. And as you say, “It was a new kind of post-punk alternative music that straddled obscurity and directness, dissent, and delicacy, unapologetic and unashamed pure pop.” I think you nailed it with that description.

PAC: Thank you. That was part of the magic of that band, was how diverse their influences were. Because all four members of the band not only came in with different influences and different types of music that they loved and sort of wanted to weave in, but they were all composers and writers and central to the band’s creative mission.

When you think about Michael Stipe, the things he heard as a kid were like bubblegum. He loved The Monkees, The Archies and late 1960s early 1970s pop stuff. But then the moment he began to hear punk and glam music, especially Patti Smith, the more he became enamored of that kind of edgier artistic sound because he was also very involved in visual art and avant-garde art of any sort.

DG: Speaking of Michael Stipe, some critics had trouble making sense of his lyrics and the early videos he created. What impact did that have on the band?

PAC: To the band, that was, as they say, a feature, not a bug. Some of this came from the fact that Michael wasn’t necessarily confident about his lyric writing or his singing at an early age. They made an esthetic out of that by saying the voice is just another instrument, so we won’t mix his singing above the sound of the instruments. We’re going to weave them all together. It will be a solid sound, and you can make as much sense of it as you want.

Meanwhile, Michael’s lyrics were very elliptical and abstract, which had its own beauty because it left room for interpretation, even if you couldn’t hear what he was saying and make out the words. The next hurdle was figuring out exactly what he meant by that. “Wolves, Lower,” for instance, or “Gardening at Night” — these obscure phrases. And some of them were weird old southern colloquialisms. And some of them were just things he made up in his mind. But that was part of the magic in the mystery of the band.

DG: Yeah, very much so. And it certainly worked to their advantage because all these fans are close listeners to the lyrics and thinking about them. That’s an incredible accomplishment. One of R.E.M.’s most beautiful songs is “Fall On Me,” one of the singles from the “Lifes Rich Pageant” album. What’s your take on this song?

PAC: It’s a very, very beautiful song. Structurally, it expresses this kind of compositional thing they fell into with these minor key verses that grow into these surging major choruses.

As a lyric and story, it’s vaguely about the fall of the environment in a sense and the idea that consumerism and environmental degradation will lead to the literal falling of the sky. So, they’re also beginning to trace this progressive political and social set of ideals that governed them as individuals that they were starting to channel into the band.

DG: On March 1, 1995, drummer Bill Berry collapsed on stage in Switzerland. What happened?

PAC: What happened was he had a brain aneurysm, so a vein in his brain burst. And it was excruciating, as you would imagine. It took them a while to figure it out and get him to a hospital. He was accustomed to having migraines, but this was a migraine on a whole other level than what he was used to.

They were in Lausanne, Switzerland, at the time, which happily turned out to be the home of the center of modern brain surgery. So, they rushed him to the hospital, and fortunately, the doctors figured out what was going on. They had developed a new strategy to take what had, up to that point, been a very debilitating, often fatal illness and make it eminently curable.

DG: Bill contributed a lot to R.E.M. besides his very precise drumming. He wrote “Everybody Hurts,” “Man on the Moon” and” Perfect Circle,” among others. How did Bill’s departure affect the rest of the band?

PAC: Well, obviously, it was jarring for them. And not just losing their friend as a part of their collective and missing him as a person and his friendship, but also the fact that he was a key member, as they all were, to their creative chemistry.

One of his super important roles was that of the band’s editor-in-chief. All the other members had their own impulses and their own temptations, and his expertise was being able to help say, “No, no, no, no, that goes on too long.” Or, “That’s not working over there, and we need to cut this down and make it more direct.”

His whole thing was, it’s got to rock. It’s got to have a groove. It’s got to work. He was the one guy in the band who they all trusted when he said the things they were doing weren’t working.

DG: The members of R.E.M. did not want to be interviewed for your book, and they’re going to regret that. You wait and see. But if you could have asked a member of the band one question, what would it be?

PAC: If I could have asked them any question? Obviously, you want to hear as much as you can about the creation of the art. But the question that I want to be answered in any book is to find out how it felt to be there. What was it like? We know what it sounds like, what you’ve said about making the music and what its performance is like on stage. But what was your actual emotional experience of being in that position?

One of the fascinating things about R.E.M. is that they were so grounded throughout it that they were almost alone among the bands that got to be that big. They didn’t have big conflicts, you know, that operatic backstory. They just seem like a bunch of well-adjusted, nice young men.