Genealogy is growing in popularity with TV shows like “Finding Your Roots,” along with Ancestry.com and other websites that allow anyone to research their family history. But what happens when you hit a brick wall?

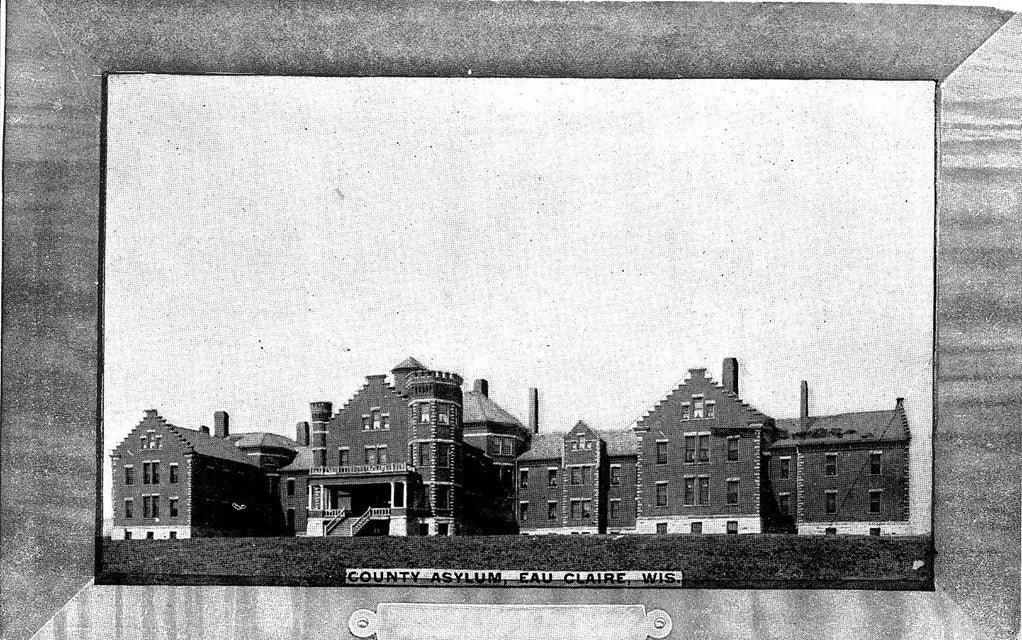

Eau Claire native Ann E. Lowry experienced that when she began researching an ancestor who emigrated from Norway in the 19th century, only to disappear from all official records. What Lowry found was a hidden dark side to local history, including a now-shuttered county insane asylum.

She’s turned that story into a historical novel, “The Blue Trunk.” Lowry spoke with WPR’s Robin Washington on “Morning Edition” about the real and fictional accounts of her family history.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Robin Washington: The book is fiction, but historical fiction, based on a real person and events. Was there really a blue trunk?

Ann Lowry: There was. In fact, the blue trunk is still in the foyer of my house. My mother had the trunk and the name on the trunk was “Marit,” who was my great-great-aunt. And when my daughter was born, I said, “I love that name. I want to name my child Marit.” And my mom said “No, you can’t do that. She was insane.”

That only increased my interest in her. And so years later, I joined a genealogy website to try to research her, but I couldn’t find any information. It was odd because she emigrated with my great-great-grandmother and there was a lot of information on my great-great-grandmother. And I also knew that Marit had actually been in Wisconsin because I had an autographed book that she signed in 1889 that was labeled “Wisconsin” and written in English.

Then I decided to research the asylum to see if I could find any records of her. And I discovered the asylum cemetery in my hometown. I saw that there were many graves that were marked “unknown.” And so I came to the conclusion that she probably spent her life in the asylum and is probably buried in one of those unknown graves.

RW: Why fiction? Why not just tell the story?

AL: I’ve always been intrigued by writing fiction. I also thought this was too sad of an ending for her. And so I thought, “I’m going to reclaim her life.” And I wanted it to be positive.

So I have some humor in it, there’s some social commentary, there are a lot of twists and turns, a little romance and I think a positive ending.

RW: Tell us about the asylum.

AL: It was called the Eau Claire County Asylum and Poor Farm. People who had mental health problems in the early 1900s, if their families had money, often went to private institutions. But this was a public institution, so the people who lived there became wards of the state and often spent their entire lives there.

One of the things that was prominent in those days, especially for women, was the diagnosis of hysteria. There were many symptoms for hysteria, including things like anxiety and the desire to have sex or desire to not have sex — a lot of things that many of us could be diagnosed with today. Hysteria didn’t drop off the DSM until 1980.

RW: What were you able to find out about why your real-life great-great-aunt went to the asylum?

AL: I don’t know. My mother didn’t know and said she was told not to talk about her. They were Norwegian immigrants and they were trying to fit in. And at the time, having an insane family member was a shameful thing.

RW: What’s your advice for folks who do find out less-than-flattering parts of their family’s history?

AL: I think we all have stuff in our families, and you know, the worst thing that we can do is to hide it. It takes the edges off of our rough edges to know that we’re more human and hopefully it makes us stronger people.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to take out inaccurate details of when the Eau Claire County Asylum and Poor Farm was built and demolished.