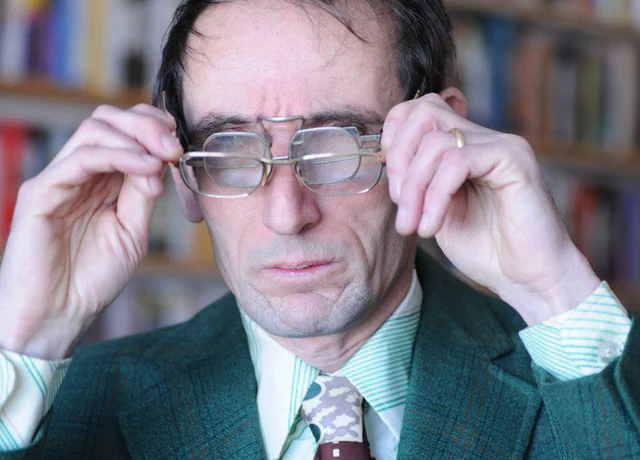

Paul de Jong hears music in found objects. In fact, he’s made a career out of finding and recording music with objects others have discarded, never imagining they could be used for music.

De Jong and his musical partner Nick Zammuto created the band The Books, which features their unique style of collage-pop music.

De Jong talked with WPR’s “BETA” about his music and a place he calls the Mall of Found.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Doug Gordon: What’s the origin story of The Books?

Paul de Jong: The origin of The Books lies in 1999 in New York City. After graduating in Illinois, many of my college mates who were musicians flocked to New York, and we all got each other apartments in the same building. It was very jolly. Nick had just graduated from Williams College and had a relationship with the sister of one of my college friends. They moved in a couple of floors away and came over for a spaghetti dinner one night.

I very quickly started sharing my then-virgin sound library, and he shared his. Within two weeks, we had our first track, which became the first track on our first record. For the first record, we worked sequentially, so what you hear is the order in which it was conceived.

We recorded most of it in Nick’s apartment in the back of the building because there was no car noise. I remember it looked out over Inwood Park, which had many crows. There are crows in the background of the recording, which we love. It adds outside noise, white noise and nature. The sound comes into the song through the window. And you hear that in the guitar loop. I brought over my instruments, Nick made that guitar loop and we just looped it. I started with my Piccolo cello, improvising over it.

Then Nick provided me with the software he was working with, and I started experimenting. The way I work with software is by trying to break it. I try to do anything that’s not supposed to be done with it, that it was not designed for. I remember I sped up many of my recordings, which acquired this folksy flavor to it. Then, we start layering samples that provide a narrative and an immediate musical connection to that guitar loop and the cello parts. We try to create some kind of fluid continuity, a musical continuity, a narrative continuity, a lyrical continuity and a balance in form.

DG: You and Nick pulled that off, mission accomplished. You and Nick are gifted musicians. Why did you decide to include found sounds in your song?

PdJ: On the one hand, I grew up with classical music in the house from birth. When I was 6 or 7, my parents started taking me to concerts at the symphony hall in Rotterdam. Every Sunday, there was a piece of contemporary music. So I was exposed to all these extended techniques, which expanded my sound world enormously, and I took to it.

I had a very odd collection of records that were kind of the leftover records in the house, little 7 inches. I had this record player that could play not only at 33 1/3 RPM, 45 RPM and 78 RPM, but it also had 16 RPM. If you play a spoken word record on 16 RPM, it becomes something entirely different than language. It becomes like a tectonic guttural sound. So, for me, spoken words didn’t only have a linguistic meaning, a meaning in language; they became a musical tool.

DG: Yeah, I love that phrase you used, tectonic guttural sounds. Bands are going to be using that name before you know it. The Books’ most streamed song is “A Cold Freezin’ Night.” It’s received over 1.8 million views on YouTube. How did you assemble this song?

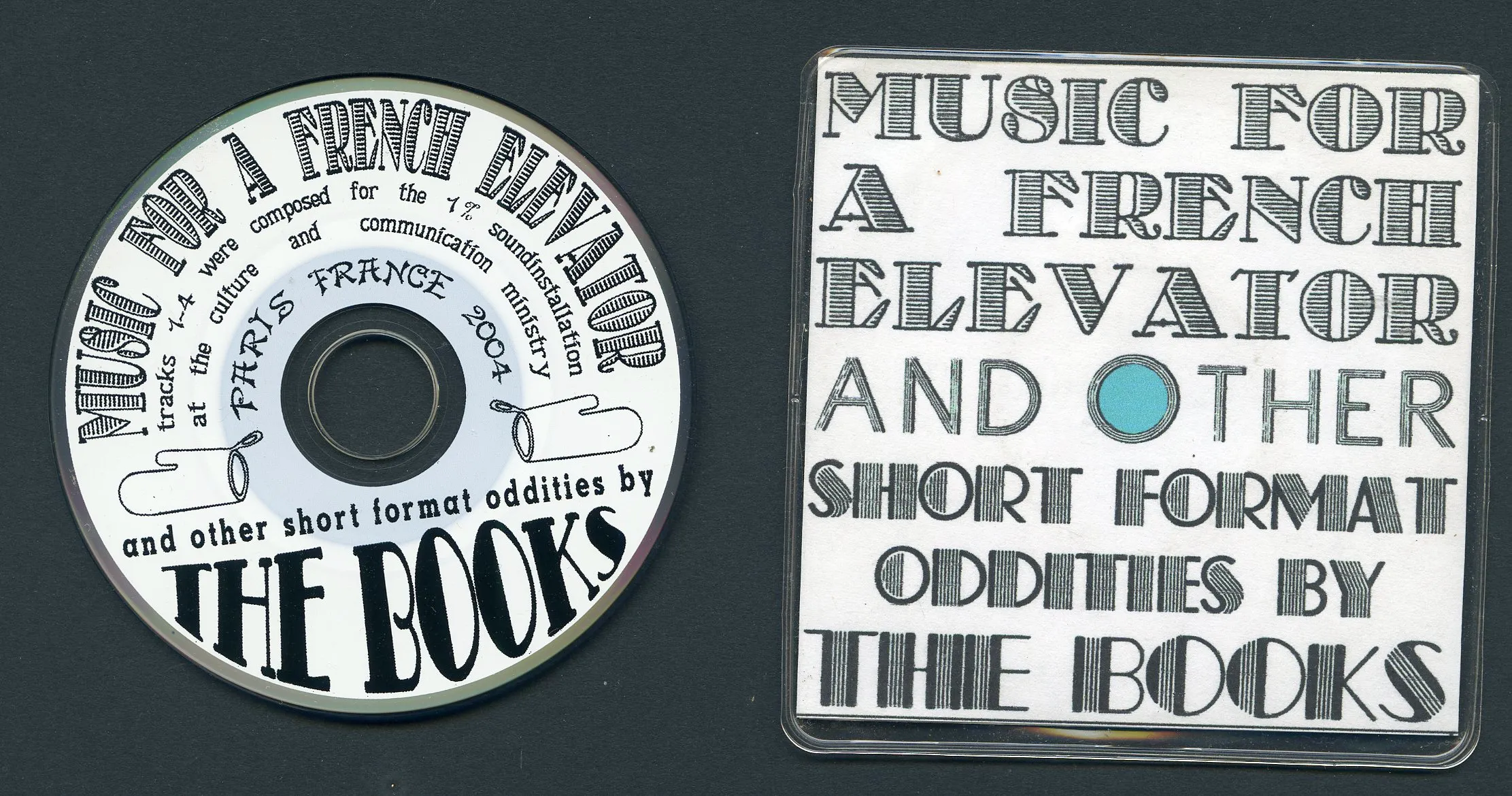

PdJ: “Cold Freezin’ Night” is late in The Books’ career. It’s on our last record. By then, my library, which is now called the “Mall of Sound,” my archive, had grown about a hundredfold easily.

Once we started touring, I realized it was essentially the greatest opportunity to have the most extensive shopping trip I could ever imagine. The shopping was almost exclusively done in used bookstores and thrift stores all over the country, and my assistants would often go after the answering machines. And among the pile of answering machines, we found every once in a while these little cassette players called Talk Boys. It was a little cassette player you could record yourself on and alter your voice. You could slow it down, and you could speed it up.

I would find these Talk Boy recorders and buy them because they had cassettes in them, and we would listen to these cassettes, and it would be all these kids playing around with their voice. And of course, they would say inappropriate things like kids do, and it was hilarious. I compiled a nice little sub-library of these Talk Boy tapes, and what these kids said made up the rhythmic sequence. We also used all these beeps from the same cassettes and some answering machine beeps to integrate into the music.

DG: You’ve made two albums since you moved on from The Books, and you’re working on a third album. Has not having Nick as a partner changed the way you create songs?

PdJ: Profoundly. When our creative partnership ended, it ended in discord. And that’s, of course, now long ago. Essentially, we are very much on speaking terms again.

I also quickly realized that I had profoundly changed through this partnership. I could not just return to who I was before The Books started. I had to somehow reconcile with the loss, find myself again alone and understand how to work alone without the luxury of collaboration.

The luxury of collaboration is that you’re complimentary, but also if you’re struggling with a particular problem, with a creative problem, you can go to your partner and trust your partner to see it from a perspective in which a solution might be found in a way that you either could never do or it would take much longer. It’s a great luxury to have two people who work well together and can solve problems for each other and change roles within that collaboration.

When I started learning to compose by myself again, I realized what an enormous amount I had learned through working with Nick, from Nick, from knowing him, and from what we invented together.

DG: Your high-ceiling studio is filled with vinyl, cassettes and VHS tapes, and you call your collection “The Mall of Found.” It’s a great name, by the way. What are your most prized possessions in “The Mall of Found”?

PdJ: There are tens of thousands of items, if not hundreds of thousands, if I count all the vernacular found photography I have in there. Books, videotapes, cassettes, LPs, objects and instruments.

They are very purposefully curated. They’re all ideas, and I have picked them out for potential or already concrete ideas I saw immediately. My most-prized possessions in the “Mall of Found” are either already autonomous works of art or have found their way into my music or video work and just found the right place.

DG: Who are your influences in the world of found sound?

PdJ: If I go far enough back, I go to my high school years and what I listened to in those days. The first names that come to mind are the composers who worked in French Musique Concrete, which is the earliest tape music from the 1950s; people like Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer. They both worked at the French radio studio, had access to tape recorders and started working with found sounds.

If you listen to those recordings, they’re widely available. You’ll immediately understand what I’m talking about because there is this very particular, incredibly musical use of spoken word, found sounds, musical sounds, studio-recorded instrumental sounds and what’s being done with it. For me, it’s not a very far stretch from what I do to this day.

DG: Who do you think you have influenced with your songs?

PdJ: I don’t know, lots of people. I’m sure because they write to me and they say, “Would you please listen to my music because I’ve been a fan for so long and I started making music, and you’ve influenced me so much,” and then I listen to it. And I often think, “Yeah, but it doesn’t sound anything like me.” It’s very satisfying to hear that people don’t try to copy what Nick and I or what I’ve been making in any way, but they get something like an idea that influences them. That, of course, is, for me, immensely satisfying.