When times get tough for parishioners at Christ the Solid Rock Baptist Church in Madison, the usual response is to come together.

The death of Minneapolis man George Floyd on Memorial Day called for that kind of togetherness. But in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing restrictions are keeping congregants apart, said pastor Everett Mitchell.

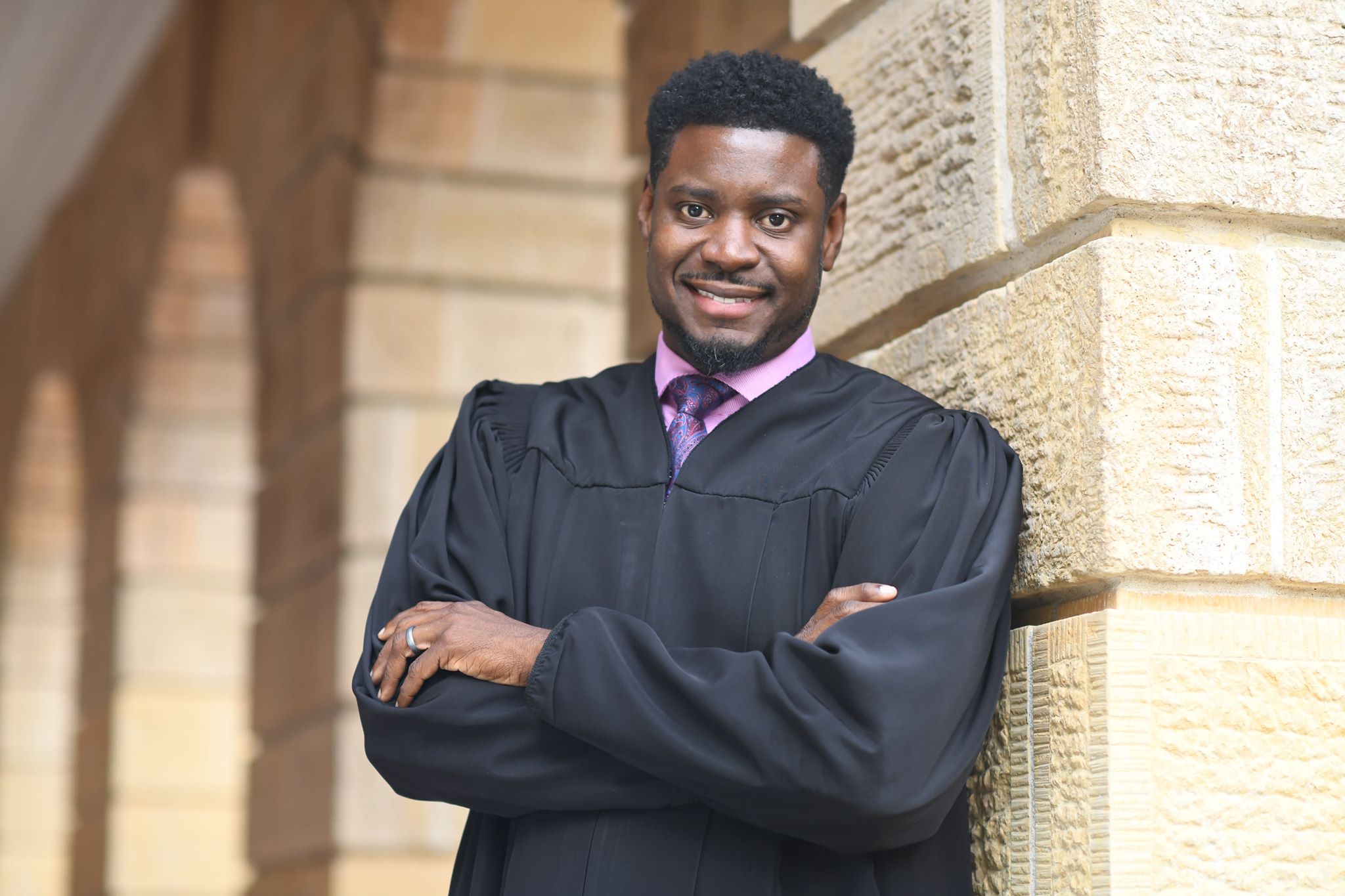

Mitchell, also a circuit court judge in Dane County, told Kate Archer Kent on WPR’s “The Morning Show” that it’s been a challenge to find new ways to help parishioners in his multi-faith community through the healing process.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: How is your community doing in this really challenging, difficult time?

Everett Mitchell: I think this is probably one of the hardest and most difficult moments in my pastorate. It’s one thing to see the horrific images and live in the realities of being black and brown in our bodies every day. But not to be able to come together in community seems to create another burden on the church, especially in my community, because we’ve always used the church as a place to come together, to heal, to scream, to laugh, to vent and strategize next steps.

It’s really causing us to reorganize our thoughts around ways to bring our community together and keep them together on such a difficult and inspirational time as this.

In our community, hugging is so healing for so many people. I’ve tried to protect and make sure that our church is a safe space. So because of that safety, that’s where people come to let their guards down and allow for the human raw emotion to come forward. We’re missing that safety of connection, which is what we lose when we can’t be in the same space together.

We had to go virtual for our services, and sometimes that’s Facebook Live or YouTube. This upcoming Sunday, we’re going to start doing outside stuff because it does need to be put back in place. We need a way for people to come together. So we’ll probably be outside in our cars in a parking lot so we can be together and see each other.

KAK: Some have talked about the act of kneeling to acknowledge injustices, validate what’s happening and join together. What do you see in the act of kneeling?

EM: In my church, we always say, “At the name of Jesus, every knee shall bow; every tongue confess.” I think Colin Kaepernick gave us a way to think about kneeling as a way of protesting to remind us of our civic responsibility to acknowledge injustices. We kneel, but we also get up to go back and fight. The kneeling is a reminder of the injustice; the standing up is a reminder we have work to do.

And, you know, when we think about the names of Tony Robinson, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tamir Rice, it reminds us that the work is not completed and the anger and the frustration a lot of people of all generations are feeling right now is because the work needs to be completed. And yes, we will kneel and pray, but then we will stand up and start walking toward our crosses and picking them up and bearing the responsibility of ensuring that justice for all people happens in our community.

KAK: Pastor Mitchell, as you form the words and you find the words for your sermons, how do you go about writing them right now?

EM: I don’t really write a whole bunch of sermons. These are such unprecedented times and we’re really looking for the spirit to kind of give us some guidance. So rather than writing, I spend my time listening to my community and listening to what they want and responding to their intimate and immediate concerns, as I think about what can inspire us to stay together.

Each Sunday is really a way for me to let them know that we’re still connected, and there are still passionate ways for us to be connected. And reminding them that in spite of losing their jobs — and a lot of my members are facing evictions as moratorium lifts — that we’re going to still stay together to ensure that none of us fall through the cracks like we’ve always done.

KAK: I would imagine with you being a judge that you think that there are things you can fix, verdicts you can make. But changing institutions is going to take more than one person.

EM: Judges are given a lot of discretion to make decisions — what I call “micro-decisions” — on an everyday basis. One of the things I did as soon as I became a judge is I started to advocate and support the removing restraints off of children. We were bringing in black, brown, low-income white children in handcuffs simply because they were kids who got in trouble. If we want our children to live and live in a just society, we can’t continue to add to their trauma. We can reduce it.

I spent the majority of the last year or two going across the state and teaching people to think about trauma-informed ways to respond to the pain that a lot of broken children have endured and breaking up what I call the child welfare to juvenile delinquency to adult prison pipeline, which is operating in Wisconsin at such a horrific rate because many of the children are invisible to the majority of the community.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.