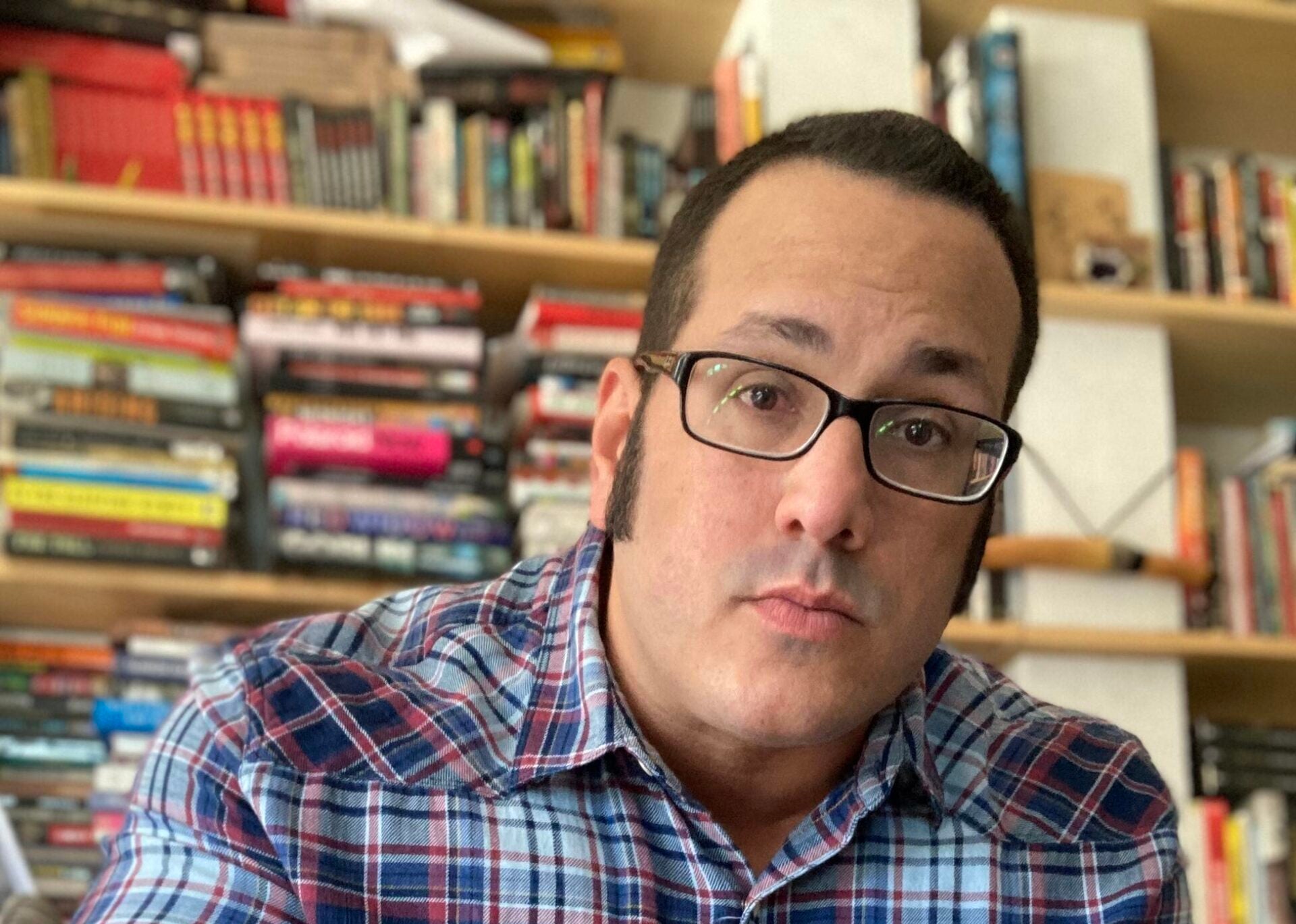

Clay McLeod Chapman is a man of many talents. He writes novels, comic books and children’s books, as well as for film and TV.

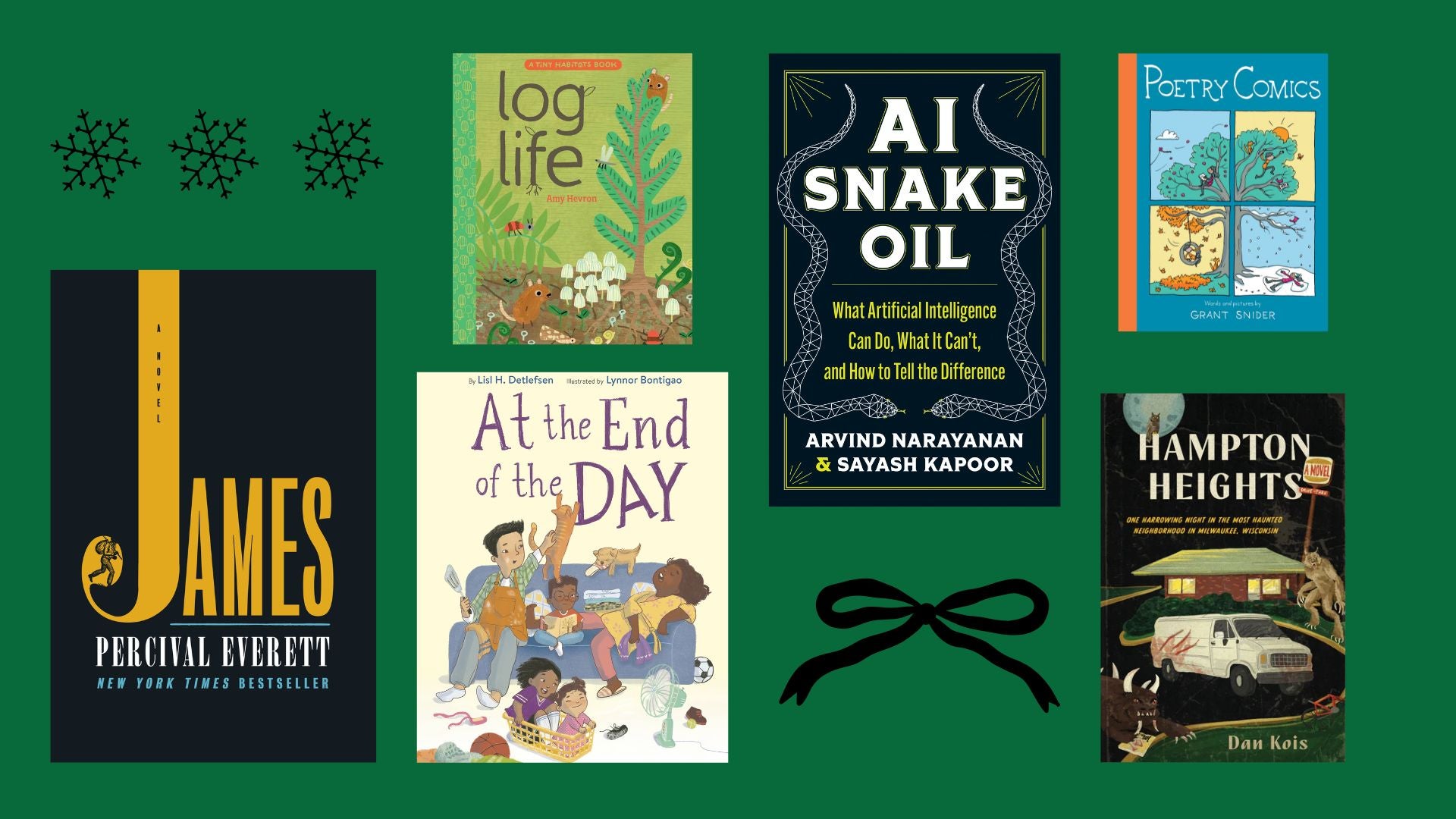

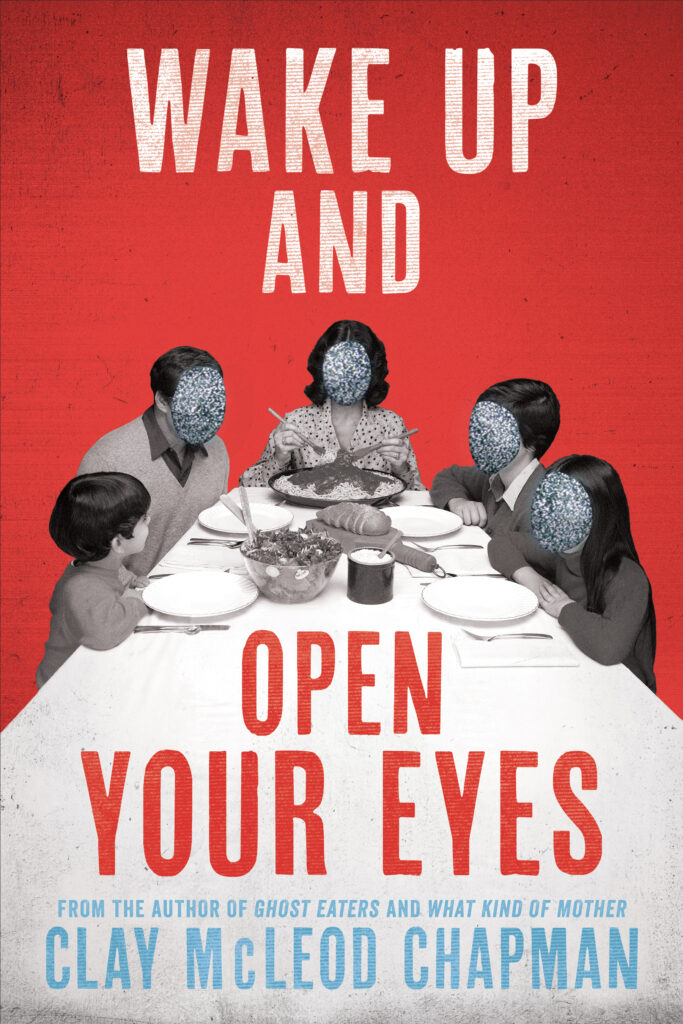

His latest book is “Wake Up and Open Your Eyes.” It’s a social-horror novel that blends relentless mass media consumption with the terror of demonic possession. The book also demonstrates McLeod Chapman’s innate ability to scare the “living you-know-what” out of us in timely and relatable ways.

McLeod Chapman recently talked with WPR’s “BETA” host Doug Gordon about how our sources of information can divide us, the utility of a good zombie metaphor, and how reality can sometimes be scarier than fiction.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Clay McLeod Chapman: To be honest, at this point in my career, I’ve kind of challenged myself to say, “You gotta put a little skin in the game.” And if I’m not frightened by what I’m writing, I don’t think the audience is going to be either.

So I’ve started writing about things that scare me. And it just so happens that I have certain members of my family who I love and have grown up with, who have shifted in their ideologies from one end of the political spectrum to the other.

There was that moment of feeling as if these people in my family have changed. They’re not the people I remember them to be when I was growing up.

So after reading a lot of articles and listening to a lot of interviews, I kept hearing this common refrain of, “It’s like my uncle is no longer himself. It’s like they’re possessed.” And hearing that enough times, it just made me feel like, oh, wow, maybe I can be quite literal-minded about that and write that story.

Doug Gordon: The first phase of your book is called “Sleeper Cells,” and it introduces us to Noah Fairchild. Can you tell us about Noah and what he experiences?

CMC: I’ll be honest with you. Noah is me. I feel like if I was gonna write this book, I had to chastise myself for my own ineffectual qualities as a gentleman in his 40s who lives in a coastal elite city. And I had to insert myself in the book, which is cardinal rule No. 1: never write yourself into anything.

But Noah in the book is a man in his 40s who lives in a coastal elite city, whose parents have slowly ebbed into their own conservative ideology. And it kind of puts a little bit of a splinter between them. And Noah is compelled to travel the six or seven hours down south to visit his parents after they stop answering his calls and make sure that they’re OK. And it turns out they’re not OK.

DG: And what happens when Noah arrives at his childhood home?

CMC: All hell breaks loose. This is his childhood home. This is where he lived as a kid, but he finds his parents in some sort of trance state or some hypnotized stupor and he can’t make heads or tails of it. And it doesn’t take long before a switch gets flipped and everything just turns upside down.

The aperture into the story is Noah and his family, but what the novel makes clear deeper into the book is that it would be easy to point a finger at 24-hour news networks, but this is also social media. This is “Baby Shark.”

Where are you getting your information from? And it’s safe to say that if you’re connected to your screen a little too much, things are not going to go so well for you in a couple pages.

DG: You explore how different generations, from children to grandparents, find both comfort and their worst fears confirmed by the media that they consume. You also deal with family and the horror of learning that our loved ones are turning into strangers. Why did you decide to combine these elements?

CMC: I have to imagine this is something that we as a country, we as a culture, are collectively dealing with. I wanna believe I’m not alone in this.

I feel this is a common refrain that you find that families are schism-ing a bit. You can have a holiday dinner and feel as if you’re living within separate realities. I just find that kind of terrifying, you know? Take the politics out of it and you can be amidst another human being and feel as if there is this chasm of information that separates you.

And it all boils down to where you get your news from, where you get your information from.

I think one could make the argument that technology is dividing us more than it is bringing us together. And that’s something we’ve been grappling with as a culture for decades.

And for me, I just kind of took the moment that we’re presently in and cranked up the volume to 11.

DG: One of the themes you explore is demonic possession. And you have said, “Take the principles of demonic possession and they overlap quite nicely with the distancing effect of media.” I love this sentence. Can you walk us through the meaning of it?

CMC: It seems so cheeky, but when I started structuring this book, I started with the basic core tenets of demonic possession.

We’ve all seen “The Exorcist” or any of its imitators, where you have a Catholic priest who walks us through these rules of demonic possession. No. 1 is infestation, and No. 5 or 6 is actual possession. These rules are there to kind of show that the demon is insinuating itself into the household, the family, the vessel, and wearing them down over time until they relent control and then the demon comes in.

But it takes infestation, obsession, you know, all of the -sions kind of come through until possession (LAUGHS).

DG: Why did you decide to use technology to enable the horror in this book?

CMC:Because I think it’s there. Take any supernatural element out of this book and you could still have a novel that explores the degradation of family members by way of their screen time, you know, how they take their information in.

And I think that possession was just a way of sugarcoating something that is quite real. I think that technology is the demon that is easing its way into household after household and wearing us down.

DG: Very much so. Why did you decide to mash up horror with politics?

CMC: Well, I think that what horror does is provide a metaphor. It provides a Halloween mask for us to put on and traipse out these ideas in hopes of having a conversation with the audience.

Whether it’s vampires or werewolves or zombies, these metaphors are there to explore the anxiety of whatever societal ills we’re going through.

DG: One of the most interesting choices you made for one of your characters is that they hear the voice of CNN’s Anderson Cooper in their head. Were you worried about how your readers would react to that?

CMC: (LAUGHS) I was worried about how Anderson Cooper would react to that.

DG: How did he react to it? Have you heard from him?

CMC: No, no, no.

DG: There’s still time!

CMC: There’s still time, that is true (LAUGHS). I am just waiting for the cease and desist letter to come in the mail.

This character is in fact losing his mind. He has fractured from reality and is narrating his own ordeal. But rather than it being him in first-person, I decided he needs to have commentary. He has to have someone reporting on his actions.

And who better to report on a coastal elite left-leaning Democratic fella than Anderson Cooper? When that light bulb went off, I was just like, “I’m committing to the bit, I am gonna go for it.” And it is amazing how much mileage you can get out of Anderson Cooper chastising yourself when you give him the mic.

DG: What do you want your readers to take away from your novel?

CMC: As long as they’re still talking to me afterwards, that’s the big test. I will be frank: It is a book that doesn’t have much hope in it, but I would argue that we’re in a place right now where happy endings are hard to come by.

For me, the book was just to give a little existential wail for 400 pages, and see if anybody wanted to shout back. I think if anyone wants to scream into the void, that is A-OK by me.