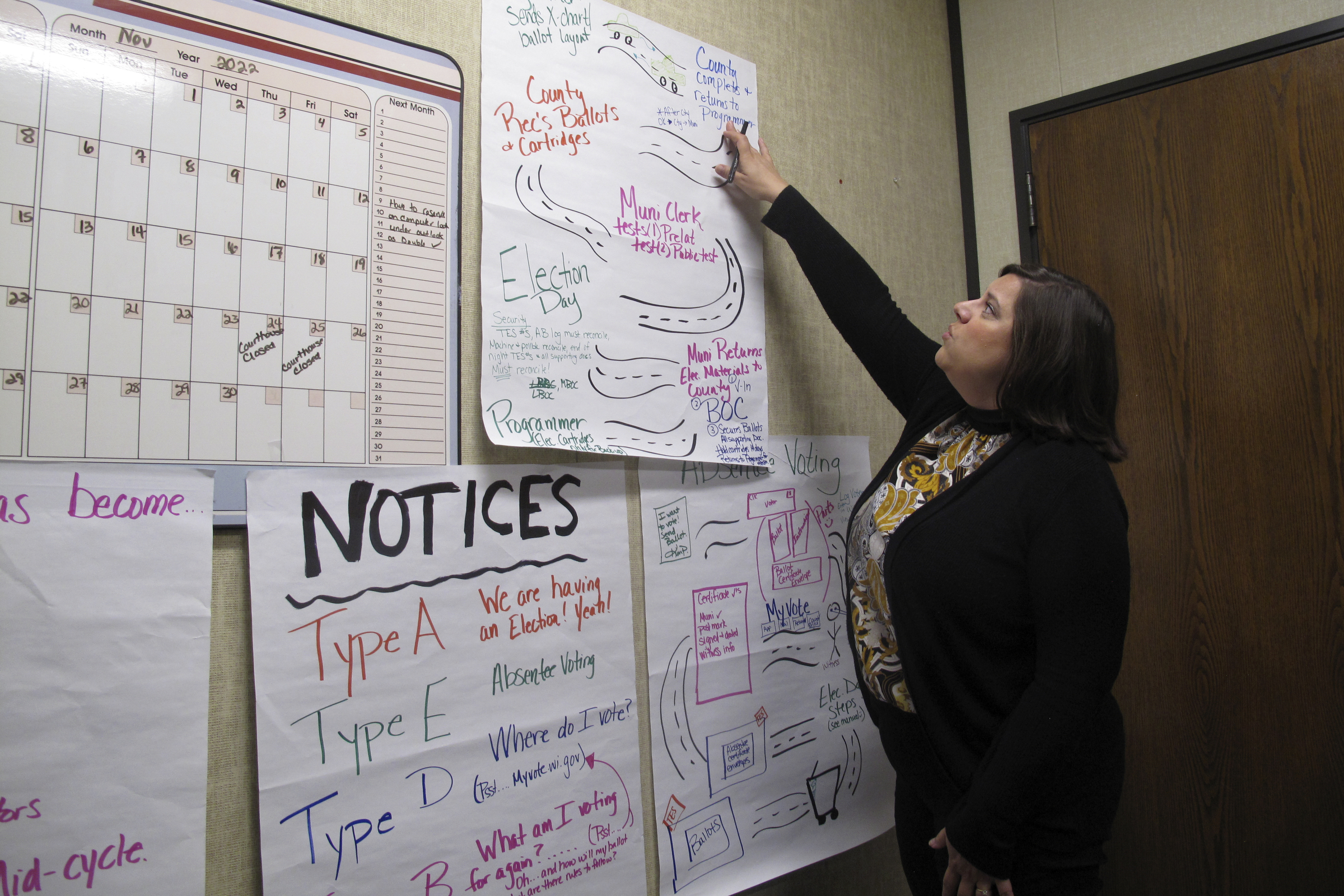

Oconto County Clerk Kim Pytleski has a series of colorful, hand-drawn posters in her office for the barrage of questions she fields from election skeptics, including one that reads, “Perception has become Reality!”

“People are throwing skepticism and these comments out there, but they’re not doing the homework on what this really entails,” she said, gesturing to a chart that lays out the chain of custody for ballots from the city, village and town polling places to her county’s vote counting center.

With political polarization reaching a fever pitch, front line election workers are reporting novel challenges such as aggressive questioning of longstanding practices. And although violent threats have been rare, some clerks are offering crisis training and stocking trauma kits — actions that years ago would have been unimaginable.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I have an ‘R’ after my name,” said Pytleski, a Republican, referring to her party affiliation for county clerk, a partisan office in Wisconsin. “That might protect me a little bit from some of the backlash that we are seeing. But … they know that the process is what I’m protecting and that I will defend it vigorously.”

While many states administer their elections at the county level, Wisconsin elections are run at the local level with some 1,850 clerks in cities, towns and villages overseeing the polls where citizens vote. It’s a complicated process that has come under intense scrutiny since former President Donald Trump falsely assailed the 2020 election results.

Pytleski, president of the Wisconsin County Clerks Association, said she learned long ago to shrug off criticism from cut-and-paste emails or scripted out-of-state phone calls haranguing her about unsubstantiated rumors of fraud.

But part-time clerks in small communities, including towns with just a few hundred people, are stretched.

“We’re losing those boots on the ground. People are saying it’s not worth it anymore,” she said.

Attacks on the 2020 election results in Wisconsin started with Trump, took root among his followers, and were fueled by former state Supreme Court Justice Michael Gableman’s fruitless taxpayer-funded inquiry. Some Republican candidates then echoed unsupported claims of widespread fraud.

“I think there’s a weariness of elections,” said Portage City Clerk Marie Moe, president of the Wisconsin Municipal Clerks Association, which represents more than 863 clerks in the state.

“We’ve had clerks leave the field,” she said. “Some (of it’s) normal attrition, … but let’s face it: (City clerk) is my full-time job. A town clerk, that’s their part-time job. And it’s more than a part-time job.”

Urban clerks prepare for worst case

It’s hard to quantify the extent of threats against people who run the polls due to the decentralized nature of Wisconsin’s elections. But elections officials from small towns to big cities say they are regularly put on the defensive by people convinced there’s coordinated fraud or vote tampering that denied Trump reelection in 2020.

Gov. Tony Evers, during an Oct. 13 campaign stop in Green Bay, told Wisconsin Watch that election deniers are doing real damage, undercutting a system that relies on good-faith public servants.

“First of all, it (rampant election fraud) is not true,” the Democrat said. “Second of all, every time they do that, they essentially are creating havoc for people at the local level.”

Evers added: “We’ve got ourselves in a bad place, we’re gonna get to the point where we’re not going to have workers to do the job.”

But that could be an overstatement, as frontline clerks say they have enough people in place and are committed to running a smooth November election — despite the pressures.

Milwaukee clerk: ‘I’ve gotten death threats’

Milwaukee has been one of the biggest targets, said Claire Woodall-Vogg, executive director of Milwaukee Election Commission.

“There’s been all sorts of conspiracy theories,” she told Wisconsin Watch. “I’ve gotten death threats.”

She said her staff have sent almost every harassing or threatening email or voicemail to Milwaukee law enforcement and the FBI.

“But for the most part, we’re just all here and focused on the same end goal,” she said, “which is making sure that anyone who’s eligible to vote and wants to vote in this upcoming election is able to do so.”

In Dane County, Stoughton City Clerk Candee Christen said election workers in the city of about 13,000 were educated earlier this month on active shooter drills and first aid as a precaution against violence on Election Day.

The community southeast of Madison also replaced the standard first aid kits with trauma kits at its four polling places. The precautions, recommended by county officials, didn’t come from any specific threats but rather a need for general preparedness.

“It’s a balance between trying to get our poll workers aware — it’s something we’ve not talked about in the past — but also not scare them away from being a poll worker,” Christen said.

Republicans ‘stocking the shelves’ with poll workers

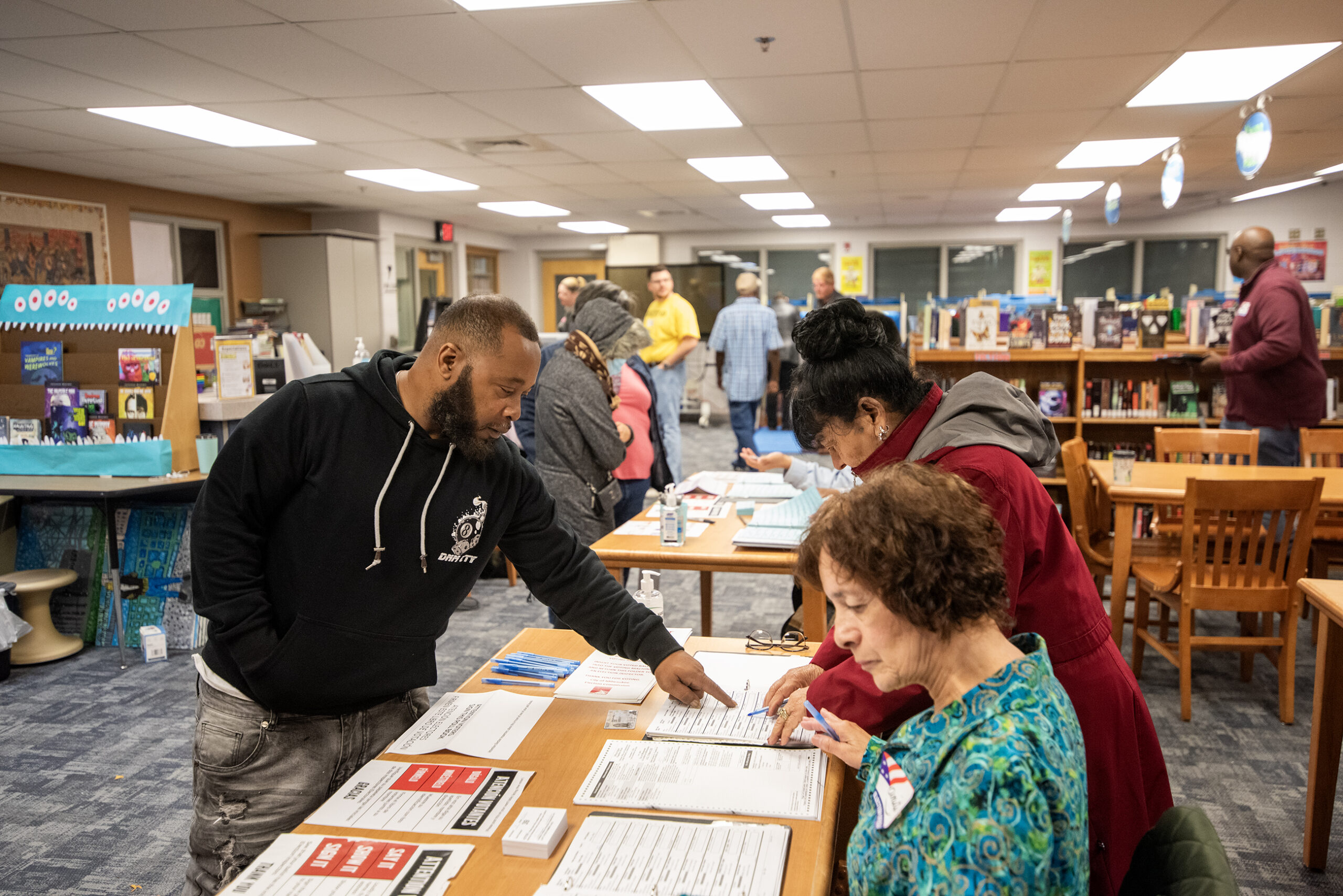

This election season there has been a surge in election workers nominated by the Republican Party to staff the polls, potentially displacing longtime, nonpartisan poll workers. Wisconsin Democrats did not answer questions about their poll worker numbers.

Municipal clerks are nonpartisan. But state law gives political parties the right to nominate election inspectors in each polling place. The formula guarantees the party whose presidential or gubernatorial candidate got more votes in that polling place’s last election to one more election inspector than the other party.

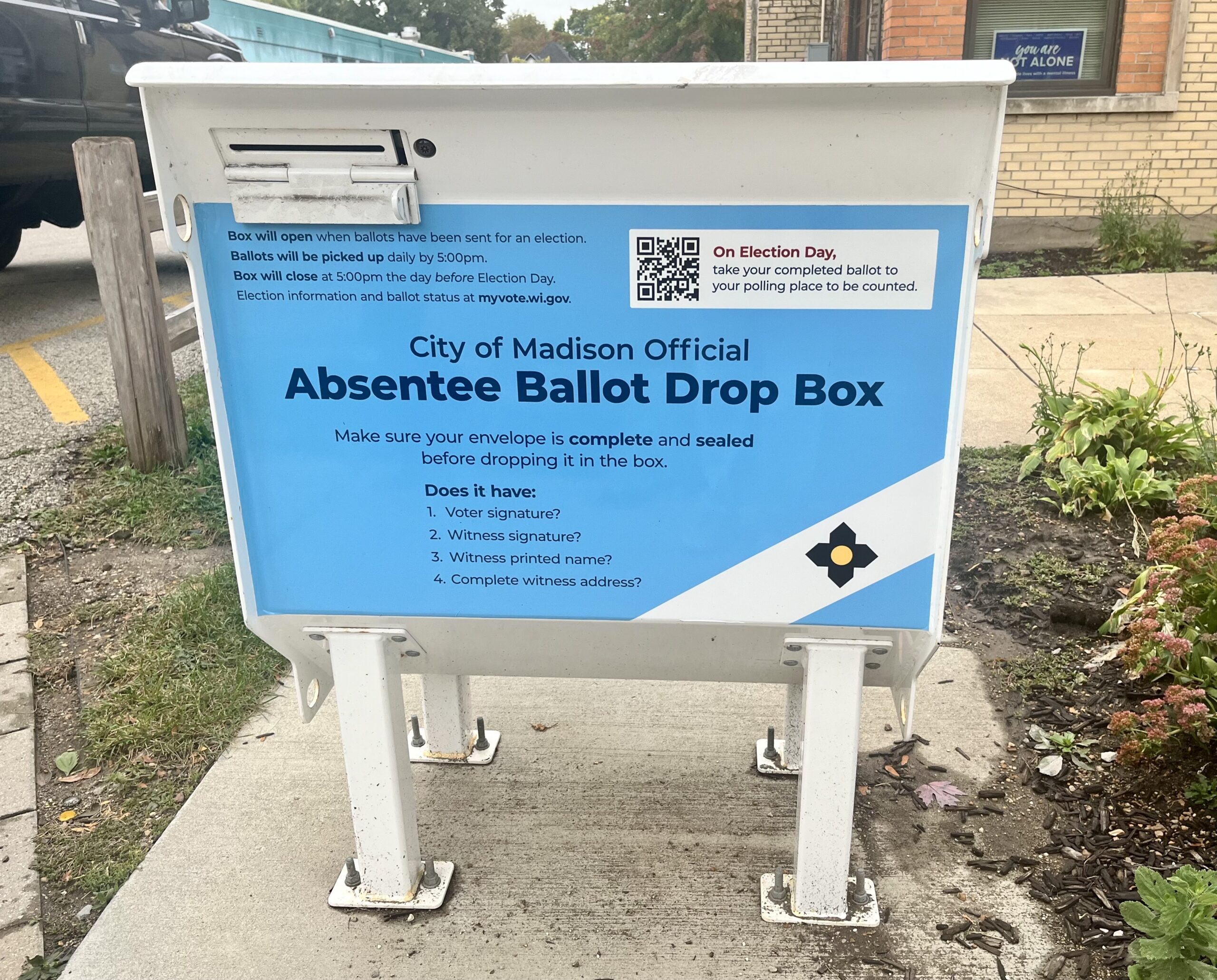

Election inspectors are empowered to decide whether an absentee ballot questioned on technical grounds — such as an incomplete address — should be accepted. And they can take a vote if there’s disagreement among poll workers.

Wisconsin’s Republican Party has invested resources in its “election integrity unit” that’s aggressively recruiting party faithful to work the polls. The state party told Wisconsin Watch it has 5,053 people signed up, three times as many nominees as in the 2020 election.

GOP leadership pointed to Brown County as an example of where the party’s ground game is a model for the rest of the state.

Brown County Republican chair Jim Fitzgerald said when he was elected in 2018, the party kept its list of poll worker nominees stuffed in manila folders; now they’re on spreadsheets.

“When I came into office four years ago here, the list of poll workers I had were probably 90 percent, unaffiliated with very, very few Republicans,” Fitzgerald said.

Fitzgerald said Republicans are taking advantage of their right to nominate poll workers this election.

When asked, Fitzgerald and other county party leaders didn’t dispute Joe Biden won Wisconsin in 2020. But he said the party’s membership is concerned about voter integrity — and it’s important that the party feed the demand of its members.

“We stocked our shelves with poll workers and poll observers, because that’s what the voters wanted,” he said. “Otherwise they were going to sit out.”

2020 election spurs volunteer

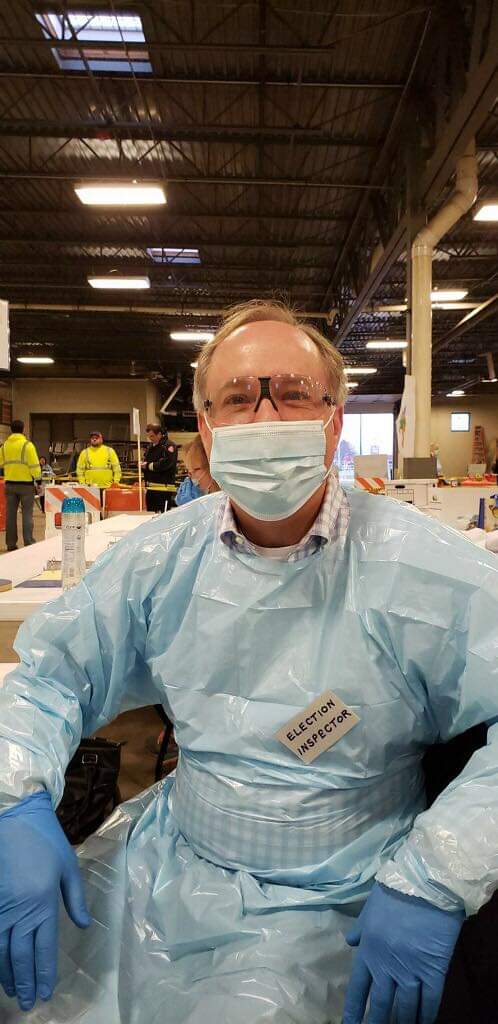

Green Bay had a chaotic election in spring 2020 when the pandemic was keeping people out of public places, the vaccines had not been released and many older poll workers were unwilling to put themselves on the front lines.

The number of polling places was scaled back from 31 to just two due to shortages of poll workers. Two years later, Republican volunteers like Matt Roeser have signed up to help out where he’s needed by the Brown County GOP.

“I wasn’t really political before the 2020 election,” the 52-year-old salesman from Green Bay said.

Roeser said he was undergoing cancer treatment in spring 2020 and his absentee ballot didn’t arrive in time.

“So I didn’t get to vote,” he said. “I was a disenfranchised voter. So I became involved and wanted to understand the process more.”

Roeser’s one of the 100 to 200 poll workers signed up by Brown County Republicans to be a poll observer or worker — he hasn’t been told which.

Brown County Democratic chair Terry Lee said much of the past chaos had to do with the public health crisis at the time, and he blames Republican state lawmakers for not allowing an all-mail-in election, as Evers had proposed.

“It was obviously not ideal,” Lee said. “But you have to hearken back to a picture from Rep. Robin Vos, Assembly Speaker, him in full hazmat gear, saying there’s nothing to fear.”

But he said his party hasn’t really changed its voting integrity strategy that much in the past two years.

“Starting in 2020, we wanted to make sure that there was a voter assistance hotline,” Lee said. “But our main goal is always to make sure that every eligible person can vote.”

It’s less clear how the Democratic Party of Wisconsin is approaching the poll worker ground game statewide.

State Democratic Party leaders would not disclose poll worker numbers. In a statement, the party said it would field workers in at least 35 of Wisconsin’s 72 counties.

“WisDems’ focus is on making sure every eligible voter is able to cast a ballot and have that ballot counted,” spokesperson Hannah Menchhoff said in a written statement.

GOP loyalty tests

Lifelong Republicans whose job requires impartiality and adhering to laws and regulations have found themselves in an uncomfortable position after anger simmered over Trump’s defeat in 2020.

Marge Bostelmann was Green Lake County’s clerk for 24 years before being appointed in 2019 to the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission as a Republican clerk designee.

She drew fire for siding with Democratic commissioners to provide nursing home residents absentee ballots during the 2020 pandemic rather than send in special election deputies while the facilities were limiting or banning visitors. She also was the only Republican member who voted to approve new Dominion voting machines, which have been a main target of Trump’s unfounded claims.

Green Lake County GOP chair Kent McKelvey responded with a public letter lambasting her work on the commission, expelling her from the party and claiming the “country is under a full-on assault by untold numbers of people, groups, and foreign actors, all wishing to gain control and fundamentally change our uniquely American way of life.”

“The Green Lake Republican Party denounced me because of my actions on the WEC,” Bostelmann told Wisconsin Watch.

But she said she has no regrets; her actions were aimed at creating free and fair elections at the state and local level.

“I’m very conservative in a lot of ways,” Bostelmann said. “But I’m not going to let the Republican Party tell me how to vote on something that makes it harder for the clerks to run an election.”

Partisan ground game intensifies

Republican leaders say municipal clerks have resisted party efforts to staff polls with their people.

“They get very defensive because in the past, they got to pick all the friends they wanted and all the people they liked to work the polls because the county parties never gave them names,” said Republican state Sen. Kathleen Bernier, a former county clerk from Chippewa County.

She recalled at least two municipal clerks in Chippewa County who resisted using the party list when hiring election inspectors during her 12 years as county clerk.

She has been critical of efforts to undermine trust in the process. But she said showing up and getting involved are the best solutions.

“Fight fire with fire, man,” Bernier said. “We can sit and complain about all the activity that Democrats do around the electoral process, but we can’t just sit back and do nothing.”

In Milwaukee, Woodall-Vogg confirmed there’s been an uptick in party-nominated poll workers from both sides. The Republicans have given her office a list of more than 200 people — twice as many as two years before — though not everyone on the list responded to work the polls. Democrats provided a similar number.

“Prior to 2020, we would never receive anything from the Democratic Party, we would always receive a small list from the Republican Party,” she said.

She plans to randomly pair Democrats and Republicans to work together on Election Day.

“We have seen it only have a positive effect,” she said. “There’s not really any hostility. They’re all there for the same reason.”

Still, Republican clerks like Pytleski in Oconto say they’re worried about injecting politics into the nuts-and-bolts of holding free and fair elections.

“Because pendulums swing,” she said. “We want to write election laws that are in place, no matter which political party has the majority, because we all have to play by the same rules on this — play nice in the sandbox.”

Jacob Resneck is a Report for America corps member. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR and other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.