In Wisconsin, the natural world is deeply woven into the state’s identity. From the dense forests of the Northwoods to the rolling prairies and farmlands of the south, the state is home to a vast array of wildlife.

But as climate change, habitat loss and economic development continue to reshape the environment, the future of Wisconsin’s wildlife is at a crossroads.

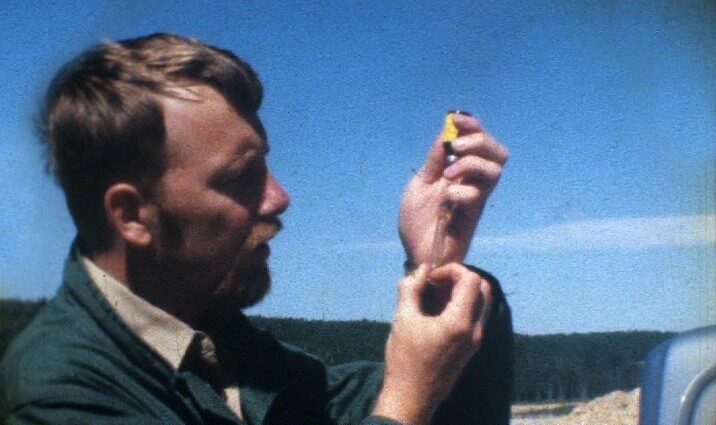

One person who has spent a lifetime studying and understanding these changes is Neil Payne, a seasoned wildlife biologist — or as he calls it, a “wildlifer.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Over the course of his career, Payne, emeritus professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, has witnessed firsthand the evolution of the field of wildlife management, an area of study that traces its roots to Wisconsin’s own Aldo Leopold, one of the most influential conservationists in history.

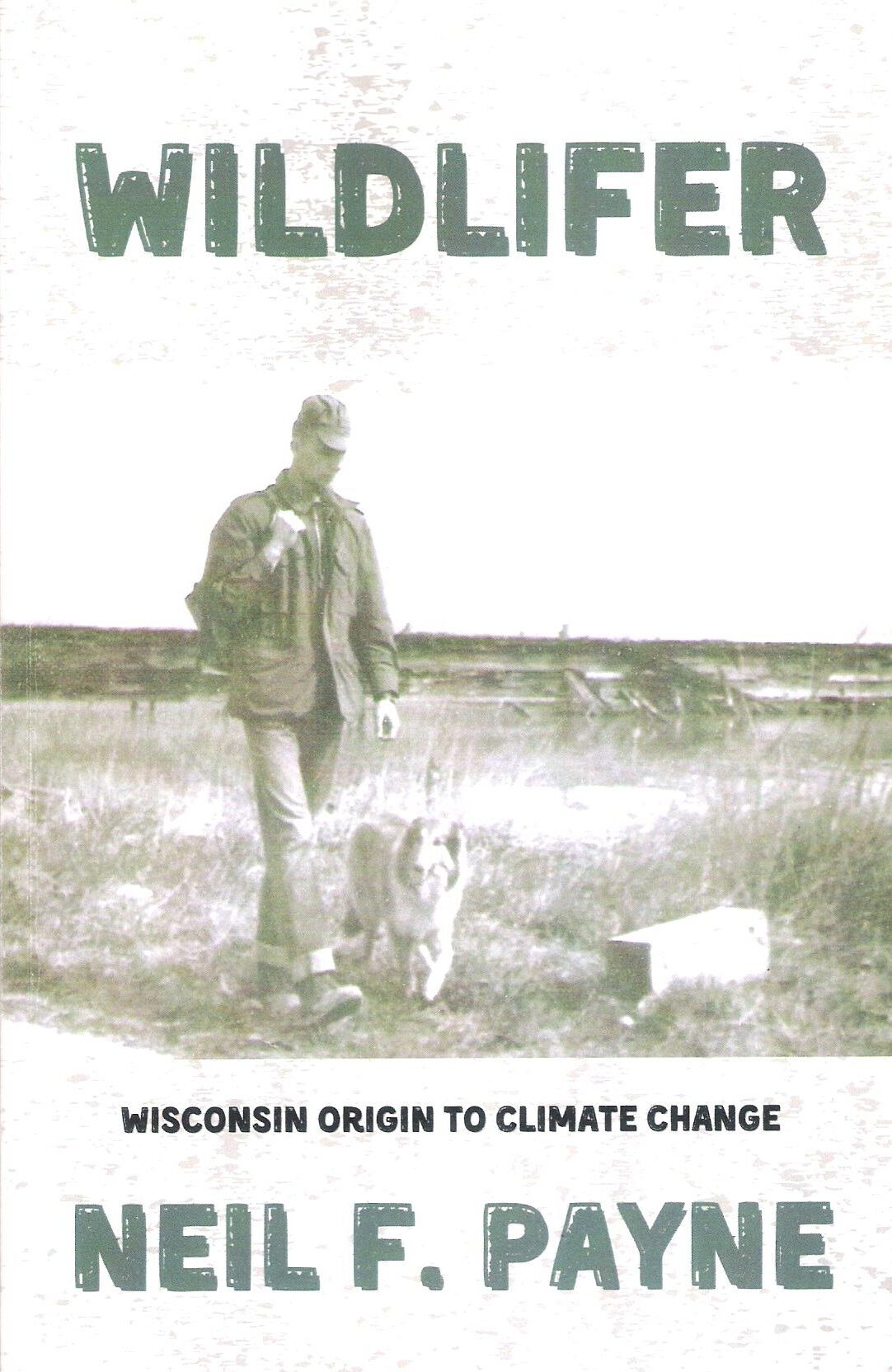

Now, Payne has turned his attention to writing, chronicling his experiences and reflections on wildlife conservation in Wisconsin. Payne spoke with WPR’s “Morning Edition” host Shereen Siewert about his latest book, “Wildlifer: Wisconsin Origin to Climate Change.”

Payne discussed how the field of wildlife management has changed since its inception and what challenges lie ahead. One of the greatest threats to Wisconsin’s wildlife, he says, is the push for constant economic growth. Climate change, too, is playing a role, shifting ecosystems and pushing plant and animal species farther north as temperatures rise.

But despite these challenges, Payne remains hopeful. He believes education and political engagement are crucial to shaping the future of conservation. Scientific knowledge alone, he argues, is not enough.

“Politicians make decisions on so many things,” Payne told WPR. “There is a term we use in our profession, biopolitics, which is when scientists say one thing and politicians say something else. When that happens, policy generally leans toward what politicians say. Because of that, I think we need to influence politicians and get them environmentally trained.”

“Wildlifer: Wisconsin Origin to Climate Change” was released earlier this year by UW-Stevens Point’s Cornerstone Press.

The following interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: You spent much of your career working as a “wildlifer.” How do you define that term?

Neil Payne: Well, it’s still not completely defined. Forester is an older term that’s well recognized in the field. Wildlifer isn’t as familiar to people. We used to be called game biologists or wildlife biologists, and there are different types of professionals working in wildlife. As a group, they’re referred to as wildlifers.

SS: How has the field evolved since you first started?

NP: It’s not very old. The forestry profession began in the late 1800s, and 35 years later the wildlife profession began in the state of Wisconsin, in Madison, with Aldo Leopold at the University of Wisconsin. It has evolved from there.

SS: What inspired you to write a book at this stage in your life?

NP: I was pretty old when I began. I was sitting in my room in Plover on the Wisconsin River looking out and saw a cottontail. I worked with cottontail rabbits as part of my master’s degree work at Virginia Tech so long ago.

I sat there looking at that thing and I said to myself, “Rabbit, you started it all.” I began to develop my thoughts along that line, started writing a table of contents, which I changed I don’t know how many times. I changed the title many times, too.

My first wildlife job was with the Newfoundland Labrador Wildlife Division right after I got out of Vietnam and the Marine Corps. I worked there for only four years, but I wrote a book about them a few years ago. I thought to myself, if I can write a book about Newfoundland Labrador Wildlife, I can write one about Wisconsin wildlife where my connection is so much longer and stronger. That’s really how it all evolved.

SS: Aldo Leopold’s legacy looms large in conservation. How did his work influence your own career?

NP: To be honest, I wasn’t really familiar with him when I was a student working on my Bachelor of Arts degree at Madison, and I took a class that he developed there.

At the time, I had no idea that I had just been exposed to one of the most iconic wildlife professionals there are in the business. From there, I went for my master’s degree and eventually a Ph.D. That’s really how it happened.

SS: What are some of the biggest threats to habitat diversity in Wisconsin today?

NP: To some extent, it’s the economy. We always want economic growth instead of looking at it in the long term, it seems to me, so we have a lot of habitat changes because of that. The number of automobiles increased substantially over the years, and of course we can’t really do anything without farming. Forestry has also been a big factor.

SS: Based on your research and experience, how is climate change currently affecting Wisconsin’s wildlife?

NP: Climate change is causing animals to change their habitat. The state is sort of divided in half, with the northern section and the southern section and an overlap with some of the wildlife and plant species.

Where they meet, I think, is moving farther north now as the climate is warming, and that is altering some of the habitat movements of wildlife as a result.

SS: Do you think the public understands the role of wildlife management, or is there a disconnect between science and public perception?

NP: I think there is a disconnect there and I think that’s due to a lack of suitable environmental education. Environmental education is so important, especially in light of climate change developing. It seems like people on the street just don’t know or have any idea about the connection. The number of people that take environmental education is, it seems, rather small compared to the number of people that know anything about it.

SS: If you could offer one piece of advice to young people interested in becoming wildlifers, what would it be?

NP: I would tell them they need to check around to see where they can get proper training if they’re interested in it and pursue it. In Wisconsin, there are two places for degrees. One is UW-Stevens Point and the other is UW-Madison.

After they get that first degree, they need to check around and see where they can go on for a master’s degree. That usually comes with financial support. Usually, it’s a year of course work and another year or two of research and thesis.

If you have an idea about something in central Wisconsin you think we should talk about on “Morning Edition,” send it to us at central@wpr.org.