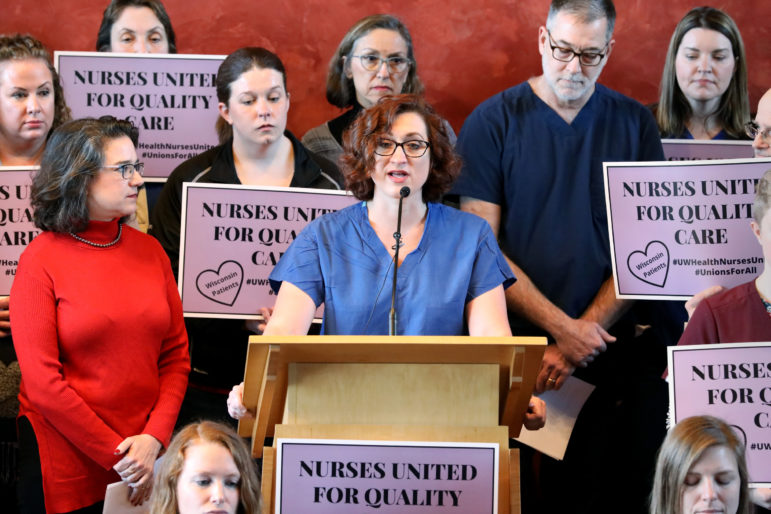

Dr. Robert Golden, chairman of the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority Board, sat in front of a sea of fed-up nurses as he tried to wrap up an agenda item at a monthly board meeting in Madison.

“We have gone beyond the allotted time,” he said, prompting shouts from a crowd of hundreds of nurses and their supporters.

“If a nurse can stand a 16-hour shift without a break, can’t you do a special meeting?” someone yelled, triggering applause across the packed auditorium at the UW School of Medicine and Public Health.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The Feb. 27 board meeting was the third in a row in which UW Health nurses asked the board to recognize their new union — so far to no avail.

Driving the unionization push: cost-cutting that nurses say has depleted ranks of hospital staff to unsafe levels. The cuts have left nurses “concerned about our licenses” and “concerned about patients,” said nurse Shari Signer, a veteran of 17 years at UW Hospital.

Research links higher patient-to-nurse ratios to increased patient mortality, though such research has not specifically examined staffing at UW Health. Higher ratios can also increase nurse burnout.

Surveys conducted at UW Health’s University Hospital, American Family Children’s Hospital and clinics suggest fewer nurses plan to continue working there. The proportion of nurses who “intend to stay” at the hospitals fell from 89 percent to 83 percent from 2016 to 2019, according to data from the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators.

The labor tensions at the UW Health hospitals offer a glimpse into a nationwide pattern of unrest.

Thousands of United States nurses and other hospital workers, including technicians, walked off the job in the past year in at least five states — Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois and Washington. Elsewhere, including at SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, nurses are more quietly fretting that cost-cutting is pushing staff to the limit.

The trend comes as hospital executives increasingly rely on manufacturing models — born out of companies including Toyota and Boeing — to bolster productivity in delivering health care. Outside consulting firms are introducing data-powered algorithms aimed at eliminating “waste,” including nurses with down time. Nearly 70 percent of hospitals across the country use a set of popular production models to improve efficiency, research shows.

Executives are using these tools to slow rising labor costs, which they consider the biggest financial threat to hospitals. But critics contend that viewing staff and patients as data points leaves out the voices of nurses as frontline caregivers — and the importance of the human touch in health care.

“We are in the midst of a grand social experiment where we’re literally willing to gamble our lives,” said Michelle Mahon, assistant director of nursing practice at National Nurses United, the largest union and professional organization for nurses in the U.S.

Nurses at UW Health are seeking to unionize with the help of SEIU Healthcare Wisconsin. Act 10, legislation that sharply weakened Wisconsin unions in 2011, barred the health care system from reaching any collective bargaining agreement with its employees. But union advocates argue that the system can voluntarily recognize their union.

‘The Era Of Big Data’

At St. Mary’s, a new Intensive Care Unit sits unused for lack of staff, according to three nurses. They were among more than a dozen current and former St. Mary’s employees interviewed for this story. All described their hospital units as understaffed. Most asked not to be named because they feared reprisals from hospital managers.

Nurses across the hospital complain they now split time among more patients than they did in the past.

Elizabeth O’Brien, a former St. Mary’s X-ray technician who now works as a traveling technician, said she saw St. Mary’s plummet from the best hospital in Madison when she started in 2002 to a hospital where patients were sometimes left to lie in their feces and urine. She said St. Mary’s fired her in December for “insubordination,” after handing K-Y Jelly to multiple hospital administrators in protest of being “screwed” over staffing and benefit cuts.

Another technician said she could not take a 15-minute break for an entire month at work for fear of leaving short-staffed coworkers in a lurch.

Most of the employees say they noticed major changes beginning several years ago after the hospital worked with a consulting group to shape staffing policies. That was North Carolina-based Premier Inc.

Nurses say a Premier tool sets daily staffing levels for each hospital unit — intensive care, or the emergency department, for example. Nurses say those levels fluctuate based upon how many patients the hospital serves and the severity of their conditions.

Hospital staff interviewed for this story say they do not know precisely how the tool calculates their productivity, but it does not reflect what they see as dangerous conditions on the floor.

“We feel we are always working understaffed and yet the numbers don’t say we are,” one nurse said.

“The goal is to run short,” another nurse said of staffing levels under the tool.

Multiple employees say the hospital will not fill vacant positions unless a department reaches 105 percent on the hospital’s productivity scale.

A labor and delivery nurse said the hospital previously assigned extra nurses to her unit, offering flexibility in case of a sudden influx of patients, “which is exactly what labor and delivery is all about.”

Much like the emergency department, most of these patients do not make appointments — they walk through the door. But the hospital has since cut the extra positions, considering them “unproductive,” the nurse said.

According to Premier, thousands of hospitals use its services to pinpoint cost savings and improve the quality and safety of health care. In a 2013 financial document, the company touted one of the largest datasets in U.S. health care and said it pulled in information from 1 in 4 hospital discharges, $30 billion in labor expenses and 2.5 million real-time clinical transactions daily.

“Health care has entered the era of big data,” Premier said in the document.

SSM Health, a nonprofit, Catholic-run health system of 23 Midwest hospitals, emphasizes a mission of providing exceptional health care that reveals “the healing presence of God.”

SSM Health signed a $7 million contract with Premier in 2005 to help cut labor costs and analyze productivity at more than a dozen of its hospitals. The company has since given awards to St. Mary’s and other SSM hospitals for improving health care quality and costs.

Premier and St. Mary’s declined to respond to questions about the tool, staffing and the specific concerns expressed by staff.

“The details around specific internal operations and HR-related policies and practices are considered proprietary and it would not be appropriate for us to discuss that information publicly,” St. Mary’s spokesperson Kim Sveum wrote in an email.

She said the hospital’s staffing procedures meet patient needs “across all our ministries — at all times.”

Sveum also pointed to the hospital’s American Nurses Credentialing Center “Magnet Designation,” which the credentialing group calls “steadfast proof of a hard-earned commitment to excellence in health care, with contented nurses at its heart.”

An extensive amount of research shows that as nurses spend less time with patients, health outcomes worsen, leading to longer hospital stays and more “adverse events” like falls and pressure ulcers, said Jack Needleman, professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the University of California Los Angeles School of Public Health.

While Wisconsin Hospital Association data show no clear increase in major falls or pressure ulcers at St. Mary’s since 2014, Needleman said short-term data are not likely to show clear trend lines “at one hospital over a short period of time.”

“We’re talking about, thank goodness, rare events,” he said.

St. Mary’s nurses say low staffing levels and benefit cuts, which have cost some staff thousands of dollars, are also prompting many to look for new jobs. And newly hired nurses are increasingly arriving fresh out of school, finding themselves immediately tossed into the fray with harried veteran nurses who have little time to offer guidance.

In the Medical Surgical Unit, one “resource pool” nurse whose job was to fill in for short-staffed teams said she saw this firsthand while taking over for an inexperienced nurse at the end of a night shift a year ago. Two of that nurse’s six patients appeared confused, one with garbled speech. The nurse recalls thinking this was strange: They both had been coherent the day before.

“Both of those patients had a stroke overnight, and no one caught it,” the nurse said. “(Six patients is) too many patients for an experienced nurse — way too many patients for an inexperienced nurse.”

Urgent Cost Cutting

A 2018 Navigant and Healthcare Financial Management Association survey found that nearly half of chief financial officers and other executives considered cutting labor costs as their top financial strategy for 2019.

At UW Health, CEO Dr. Alan Kaplan shared his concerns about costs in a 2017 message to system employees, describing an “unprecedented shift in our industry” where the growth of expenses is outpacing revenue.

“We have no choice but to act decisively. We cannot stand by and watch our financial security decline,” the message read.

With help from Prism Healthcare Partners, a Chicago-based consulting group, UW Health set an ambitious financial target: save $80 million over 18 months.

The dire-toned message startled hospital employees.

“It was very strange because we’ve always been a fairly financially sound institution,” said Kate Walton, an emergency department nurse who has spent more than three years at University Hospital. “It was very much sold to us — if we didn’t make these cuts, we’re in a lot of danger.”

Over the following months, UW Health reduced the number of paid working hours of its staff “through managing overtime, reducing onboarding costs, eliminating management positions and not filling open positions where volume did not warrant,” said Tom Russell, a UW Health spokesperson. “But we did not eliminate any currently employed nurses to achieve this reduction.”

Still, by December 2018 the health system employed 284 fewer nurses than it did a year earlier. Nurses’ phones filled up with cute, yet desperate messages from colleagues asking for extra staffing help, including: “Roses are red, violets are blue, we need a sixth RN and I think it’s you.”

The quality of some medical supplies declined, nurses say. Plastic urine collection bottles, they contend, now feature sharp edges that cut male patients.

But as nurses do more with less, they question whether hospital executives are showing the same restraint. Kaplan’s compensation increased to $1.5 million in 2018 from $900,000 the previous year. And UW Health in 2018 announced plans to build a $255 million clinic on Madison’s east side.

“I think that there is a belief among nurses that if we really had this deficit, why would we build a new hospital?” said Courtney Maurer, a cardiac intensive care unit nurse.

Kaplan was not available to be interviewed for this story. But he appears to have anticipated the challenge of pushing his employees to cut costs while UW Health is investing in new land, construction and technologies.

“I always hate to talk about profit — about margin,” Kaplan told hospital staff in a September 2017 town hall. “We’re in health care. When we’re seeing patients, when we’re talking to patients, that’s all we care about in that moment.”

But Kaplan described a host of challenges that were narrowing hospital profit margins, according to a 2017 Wisconsin State Journal article, including taking on more Medicare and Medicaid patients and a “skyrocketing acceleration of costs in pharmaceuticals and medical supplies.”

Russell says UW Health exceeded its $80 million savings target, reaching $105 million in savings since 2017. Reduced labor costs accounted for $42 million of those savings.

UW Health and Prism have since touted the health system’s cost savings to other health care executives, including in an August 2018 webinar titled “How UW Health System Drove Millions in Savings with an End to End Labor Management System Solution.”

A plunge in staffing costs was “led and really role modeled by our nursing departments,” Wayne Frangesch, then-UW Health’s chief human resources officer, said during the webinar.

UW Health developed a productivity tool — similar in spirit to what St. Mary’s uses — to track the hours spent on each patient, comparing those figures to targets.

Nurses say they felt more strain.

“We’ve been busy. We’ve had patients in the hallway,” said Mariah Clark, an emergency department nurse.

Clark said her department is lucky sometimes, getting a couple of more nurses than the UW model prescribes. But those nurses are quickly sent home — forcing them to go unpaid or use their vacation time. That only increases stress on those who remain, she said.

Walton, the emergency nurse, recalls recently staying an extra two hours beyond a typical 12-hour shift in the emergency department to help a relatively new nurse taking over care of a critically ill patient.

“I knew that she didn’t feel comfortable and there wasn’t really anybody else that could stay and help,” Walton said.

Russell said non-physician staffing at UW Health are “back to the same levels they were before addressing the financial issues in 2017.” Still, the volume of inpatient discharges at University Hospital has increased year over year since at least 2014, according to American Hospital Directory data. Data were not available for American Family Children’s Hospital.

The ‘Lean’ Model

Mahon, of National Nurses United, describes a shift from a “caregiving model” of health care to a “manufacturing model” focused more on efficiency, standardization and technology.

One such popular manufacturing model is called “lean,” modeled on how Toyota produces cars.

UW Health in 2018 contracted with Virginia Mason Institute, known as a leader in applying lean principles to health care. The Cap Times, Wisconsin Public Radio and Wisconsin Watch obtained that contract through a public records request, but UW officials redacted key sections, including how much the system paid Virginia Mason, and specific services provided. SSM Health, which is not subject to state open records laws, has also embraced lean.

In an interview, Lean Global Network Chairman John Shook, who applied lean principles while working for Toyota for 11 years in the U.S. and Japan, said lean emphasizes creating value while minimizing waste, “providing the customer with what they really need — nothing more, but nothing less.”

Lean is credited with helping some hospitals reduce ER wait times, reorganize surgical supply closets and encourage new mothers to show up for postpartum checkups.

Nearly 70 percent of U.S. hospitals use lean or a similar model to improve efficiency, University of California-Berkeley researchers found in a survey conducted in 2017. However, just 13 percent reported having “maturely” and widely implemented the methods.

Dr. John Toussaint, founder of Appleton-based Catalysis, which teaches lean to hospitals, said many hospitals have misapplied the model. Some hospitals will use it to free up nurses’ time — and then cut them for being unproductive.

“There’s a lot of ‘lean consultants’ that have their tools that they ram down people’s throats,” Toussaint said. “If the staff are not engaged, and they’re mad at it, you’re not doing (lean) right. You’re doing something else.”

Shook acknowledges that hospitals do not always apply lean correctly.

“Nurses really get caught in the brunt of this, the broken health system that we have,” Shook said.

Francesca Nicosia, a medical anthropologist at UC-San Francisco, found similar tension while surveying nurses about implementing lean at a hospital in northern California.

“Nurses were the ones who were being asked to carry out the bulk of these process improvement changes,” she said. A common phrase she heard from nurses: “Lean is mean.”

Hospitals have always focused on productivity, according to Rick Gundling, senior vice president at the Healthcare Financial Management Association. He notes, though, that hospitals now have access to so much data that allow for more “precise” and “predictive” modeling of their staffing ratios.

“It should cause a conversation. Numbers aren’t meant to be just dictatorial,” he said.

That conversation may be missing in hospitals across the nation.

In Chicago, over 2,000 nurses at the University of Chicago Medical Center went on strike in September and then threatened to strike again in November after months of negotiations with the hospital. As with the nurses in Wisconsin, staffing levels fueled their concerns. Their new contract boosted nurse-to-patient ratios.

In January, thousands of nurses and health workers at Swedish Health Services in Seattle went on strike, as their contract negotiations with the hospital broke down. Once again, they chiefly complained about staffing levels. That dispute has yet to be resolved.

Pouring From An ‘Empty Cup’

As UW Health nurses push executives to recognize their union, St. Mary’s staff say their shortage is only worsening. Two nurses point to a recent weekend in the labor and delivery unit to illustrate the rising stress.

A woman in active labor was calling for pain medication, only to be left alone for an hour as her nurse assisted with an emergency elsewhere.

“You go home so worn it’s a chore to eat … it’s hard to sleep,” said one of the nurses. “We try our damndest to give them the care they deserve and keep them safe. A lot of us are burned out — you can’t pour from an empty cup.”

With less time to rest and more time spent scanning and moving up to 60 patients a day, technicians say they are suffering more arm and back injuries. One technician said there is no space for “revealing the presence of God” that was core to St. Mary’s culture and is still displayed on billboards around Madison.

“While I myself am not Catholic, that absolutely spoke to me and why I did what I did,” she said. “I don’t even know if I make eye contact with my patients most of the time. It’s literally a production line.”

Editor’s note: This story was a collaboration between Wisconsin Watch, the Cap Times and Wisconsin Public Radio. The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (wisconsinwatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.