A Dane County judge rejected an emergency request to allow election clerks to count absentee ballots with incomplete witness address information.

The request came from the League of Women Voters of Wisconsin, which asked Dane County Circuit Court Judge Nia Trammell for an emergency injunction Oct. 13.

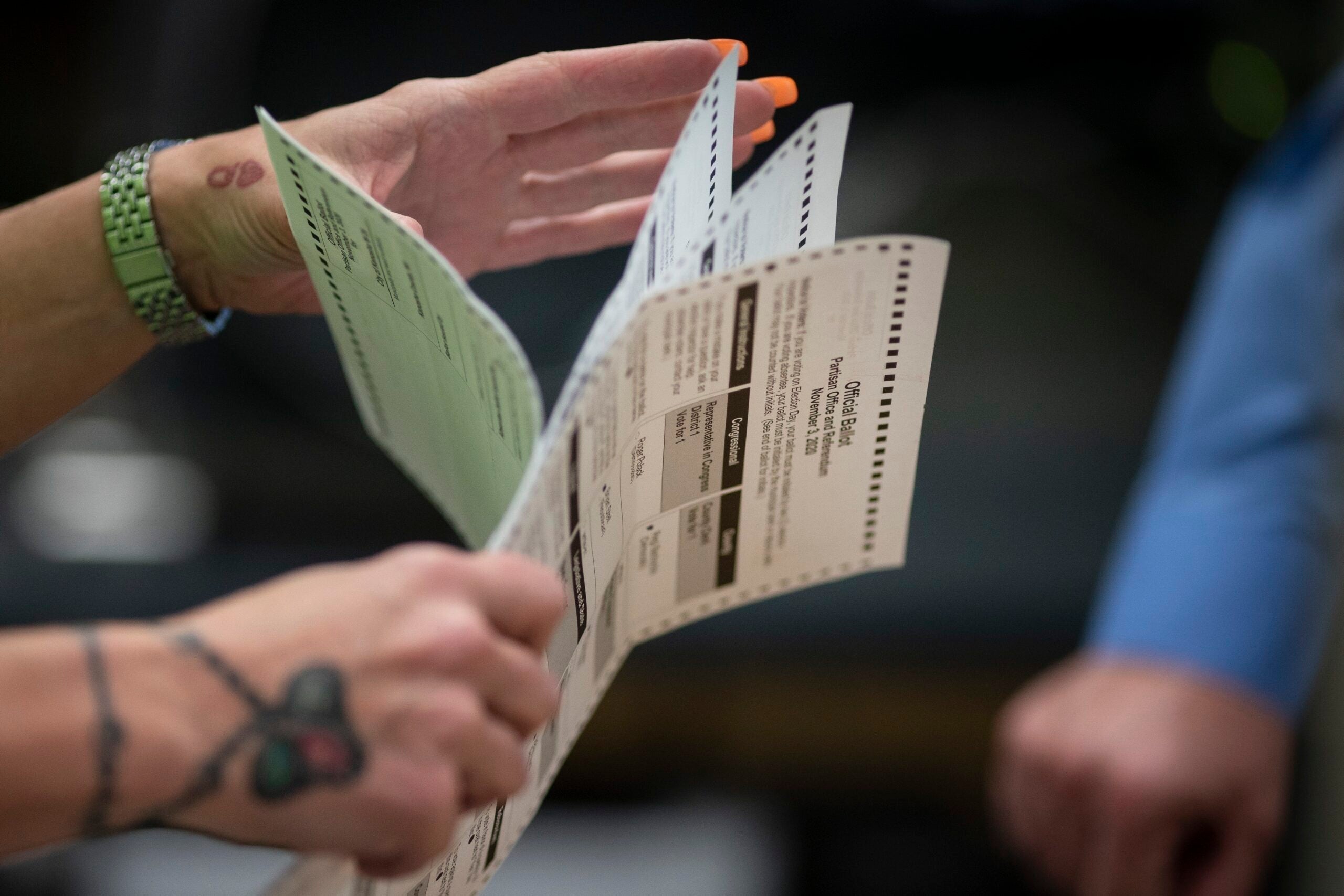

The group filed a lawsuit against the Wisconsin Elections Commission in late September in hopes the court would clarify state statutes barring clerks from counting absentee ballots if envelopes, known as witness certificates, are “missing the address” of that individual.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Legal arguments in the case focused on the meaning of the word “missing” in the statute governing absentee ballots.

LWM argued that “the common sense, plain-language definition” of the word “missing” only applies if the witness address field is completely blank.

Attorneys representing the Wisconsin Elections Commission and the Wisconsin Legislature argued the opposite, saying a commonsense reading of absentee voters laws indicates the word “missing” in statute cannot mean absentee ballot envelopes are acceptable unless the witness address is completely blank, instead focusing on the absence of any portion of an address.

In an oral ruling Wednesday, Judge Trammell said parties requesting injunctions must prove, among other things, that they are “necessary to preserve the status quo.”

“I believe that to issue a temporary injunction would upend the status quo, not preserve it,” said Trammell. “I also believe that the fact that the election is all but two weeks away lends some credence to the argument raised by WEC and the Legislature that any decision issued by the court granting the temporary injunction would frustrate the electoral process by causing confusion.”

If the court did issue such an injunction, Trammell said, voters could conclude that any markings made by a witness would suffice and a higher court could disagree if WEC or the Legislature appealed her ruling.

“And if that is the case, then there is a risk that such voters’ absentee ballots may not be counted for the upcoming election,” said Trammell.

The suit is one of several legal battles that have focused on absentee ballot witness certificates and 2016 guidance from WEC that stated clerks could correct missing address information on envelopes if they could verify a witness’ address with other information on the envelope “or other reliable extrinsic sources.” The idea behind the policy was to prevent voters from being disenfranchised due to mistakes made by witnesses.

In early September, a Waukesha County Judge issued a temporary injunction blocking clerks from correcting incomplete witness addresses on certificates.

On Oct. 6, Waukesha County Circuit Court Judge Brad Schimel, a former Republican Wisconsin Attorney General, ruled clerks cannot destroy previously submitted absentee ballots to allow voters to cast new ones due to mistakes or to change their votes.

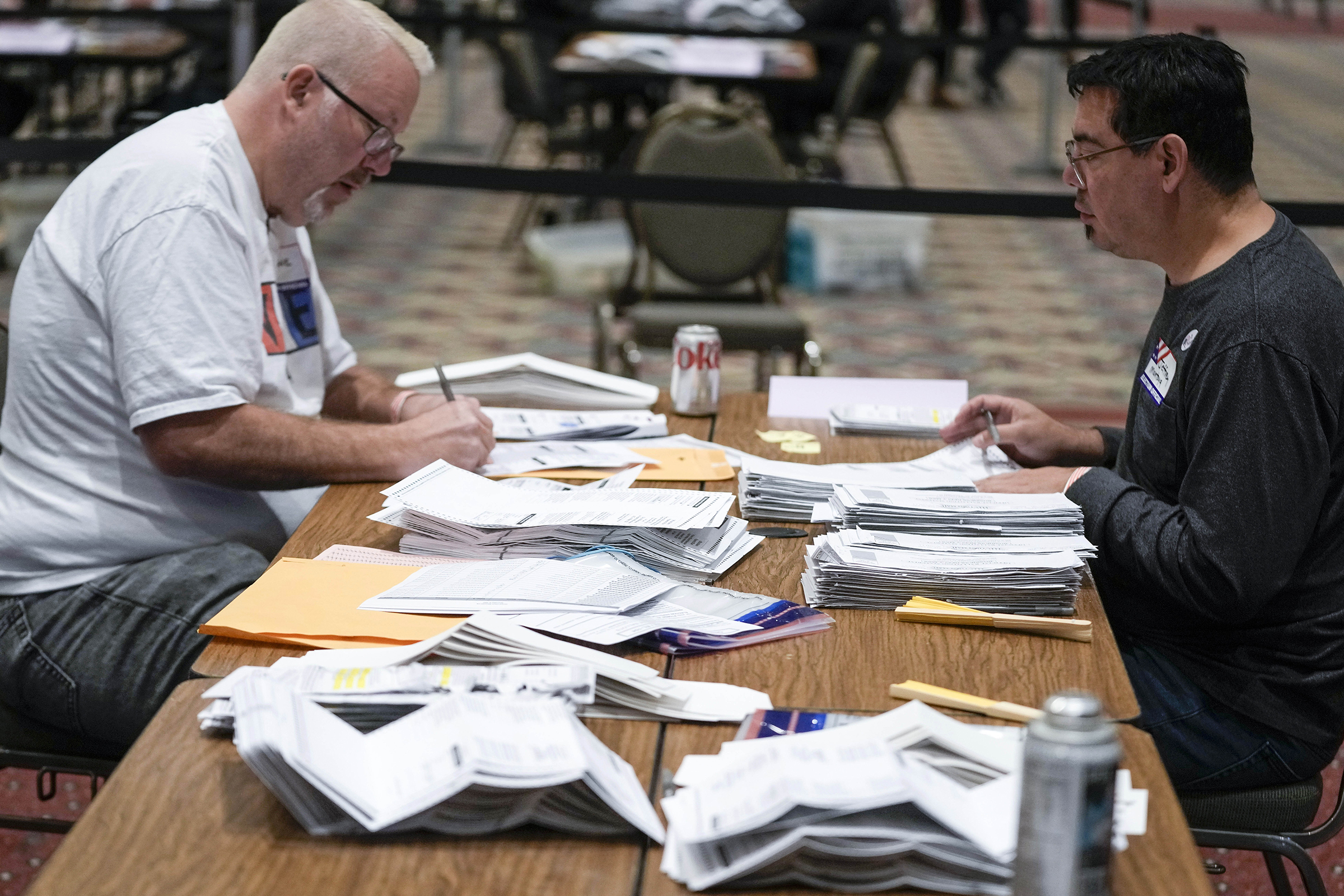

As of a Wednesday, WEC reported that 510,699 absentee ballots have been requested by voters ahead of Wisconsin’s Nov. 8 midterm election and 305,453 have been returned.

Last year, the nonpartisan state Legislative Audit Bureau reviewed 14,710 witness certificates accompanying absentee ballots in the 2020 presidential election. It found that 1,022, or 6.9 percent, of certificates had partial witness address information.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.