Gary Swain and his family operate what he calls the quintessential Wisconsin dairy farm.

“It’s a tiny red barn with a white roof, with a blue silo, with black and white cows running around everywhere,” said Swain.

Swain’s family has been farming around the Town of Christiana for about 180 years. The seventh generation dairy farmer owns a small herd of around 25 cows with about 120 acres of land, on which he grows corn and hay to feed his cattle. To supplement their income, Swain works part time as a dairy nutritionist and his wife has a full-time job off the farm.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Keeping the farm going is a labor of love for his family, their three kids, his brother and their retired parents who help as much as they can. But, Swain fears the recently approved Koshkonong Solar Energy Center threatens their ability to keep the farm running.

“If my cows’ production starts dropping, if we start losing crop yields (because they’re) overrun by wildlife that are moving west because they can’t get to these fields and stuff like that, we’ll be done for,” said Swain.

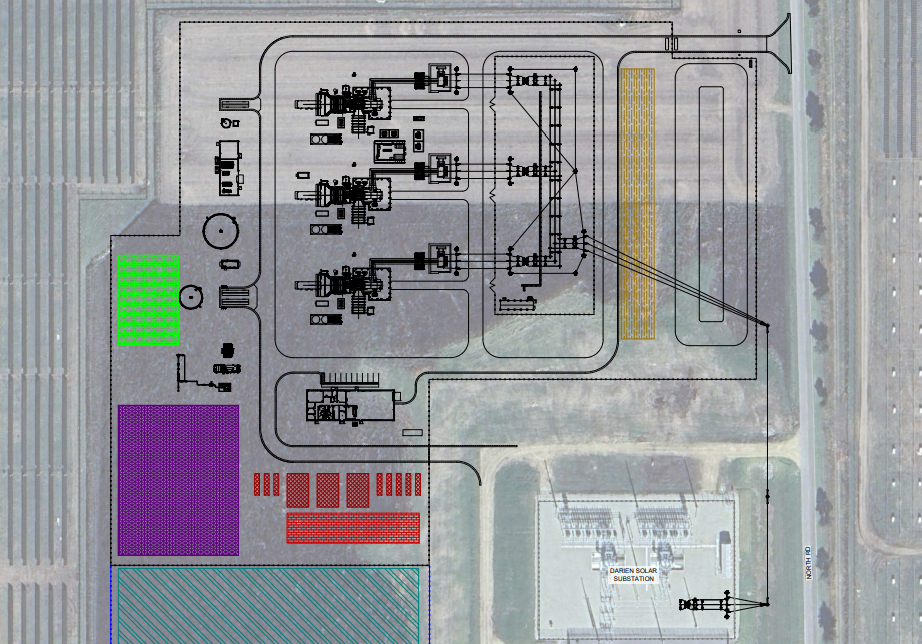

Invenergy, a Chicago-based developer, has contracted with landowners on around 4,600 acres for the roughly 2,300-acre solar array in the towns of Christiana and Deerfield. The project would host 300 megawatts of solar — enough to power 60,000 homes — and 165 megawatts of battery storage. Utilities owned by Milwaukee-based WEC Energy Group and Madison Gas and Electric plan to spend $649 million to buy the plant.

Swain hopes the courts will be more sympathetic to their concerns now that the Town of Christiana filed a lawsuit on May 26 in Dane County Circuit Court challenging the Wisconsin Public Service Commission’s approval of the project. The town argues the state’s largest renewable energy project violates the Wisconsin Constitution and the commission’s own rules. The PSC declined to comment on pending litigation.

Attorney H. Stan Riffle, who represents the town, said Invenergy’s land leases with property owners exceed the 15-year term spelled out in the Wisconsin Constitution. Invenergy has lease agreements with landowners that last 25 years and can be extended for a maximum 50-year operating term.

Commissioners have said residents’ concerns over lease terms lacked merit, and utilities have accused opponents of using an “antiquated” and “inapplicable” section of the state’s constitution to halt the project. Even so, Riffle said the project shouldn’t have been approved as a merchant plant under state law since it’s being bought soon after by utilities. Those plants don’t have to consider alternatives or justify costs unlike regulated utilities.

In the PSC’s final order on its decision, the commission said the potential for utilities to buy such projects in the future doesn’t change their status.

“To the extent that certain intervenors find fault with this framework, their argument is with the Legislature and not with the Commission,” wrote the commission.

Swain and other residents have raised concerns that the solar and battery project will harm the environment, tourism, property values, future growth in the village of Cambridge, and lead to the loss of prime farmland.

Residents like Tara Vasby say the town’s lawsuit may be the first of several legal challenges.

“For this specific project, it’s too big for this community. It’s too close to the community. It’s too close to the schools,” Vasby said. “It’s not the right size for this community and this area.”

Residents like Vasby are worried about the project’s proximity to homes and the Cambridge Elementary School. Others like Swain are concerned about the plant’s potential to create stray voltage or batteries sparking fires. Stray voltage is low-level voltage between two points in animal confinement areas where electricity is grounded, according to the PSC. Swain said stray voltage has been linked to cows drinking less water, which can lead to lower milk production.

Michael Vickerman, policy director for RENEW Wisconsin, called concerns about stray voltage a red herring. He added fires are an ever-present risk in a variety of industries, noting battery storage doesn’t present a unique threat.

“This lawsuit is the result of a couple of individuals and Town of Christiana government that just don’t like solar on agricultural land,” said Vickerman. “That’s all it comes down to.”

Vickerman added large solar farms are operating in Wisconsin without causing any environmental damage.

“It displaces fossil fuel generation with a zero-carbon source of electricity. It provides firm capacity at a Dane County location that will help MGE and We Energies and Wisconsin Public Service shut down the Columbia coal-fired plant in Columbia County,” said Vickerman.

But, Town of Christiana resident John Barnes questions the pay-off of intermittent energy sources like solar and wind that rely on fossil fuel power generation as a backup when the sun’s not shining and the wind isn’t blowing.

“If you’re trying to accomplish carbon dioxide reduction, you’re probably really not doing that,” said Barnes.

Yet, environmental groups like Clean Wisconsin and the Sierra Club have said the project is a step forward that protects public health, avoids water pollution and reduces carbon emissions by 15 to 20 million tons over its lifespan.

The project is also helping some farmers in the area stay in business through lease payments, said Matt Johnson, field operations director with Wisconsin Land and Liberty Coalition.

“It’s really beneficial because crop prices fluctuate. Sometimes they’re high. Sometimes they’re low. But, these land lease payments are written into contracts and can provide stability to farmers,” said Johnson.

Invenergy hopes to begin construction late this year or early next spring. The project is slated to go in service in 2024.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.