People in more than 22,000 Wisconsin homes may be consuming unsafe levels of lead in their water, but testing for the toxic metal is difficult and it often goes undetected.

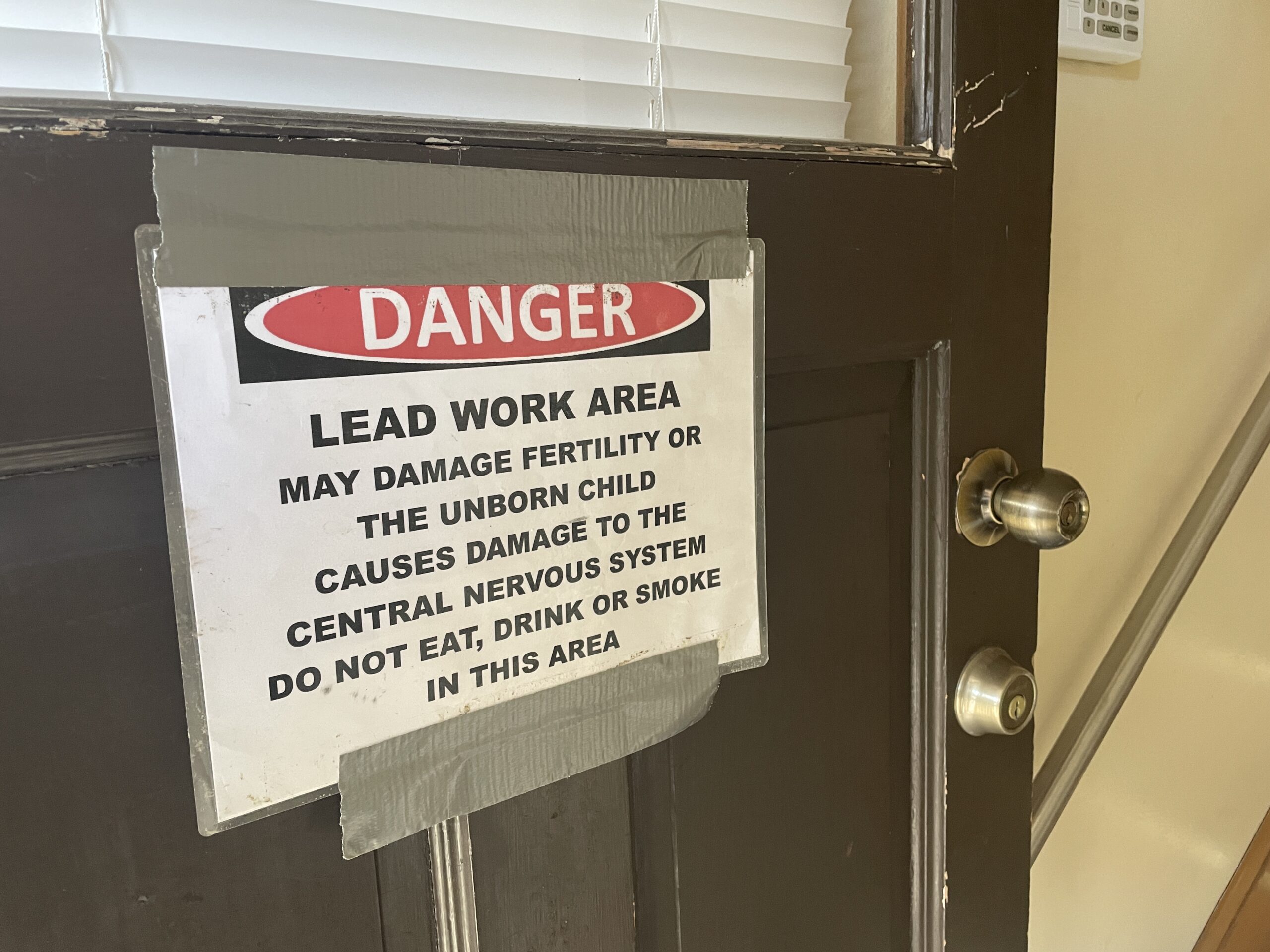

In 2014, nearly 4,000 Wisconsin children were found to have elevated blood lead levels, many of them in Milwaukee. Ramona Jensen is a lead liaison at the city’s Social Development Commission who helps find and eliminate lead hazards in the city. She said the motivation for her work is personal: She believes she and her son were both lead poisoned from exposure to lead paint.

“Lead causes brain damage. Lead causes cognitive problems, developmental problems. It has been linked with ADHD. It causes impulsive behavior, it causes aggressive behavior,” said Jensen. “And then a host of health problems that go on into adulthood.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Ramona Jensen, a lead educator with the Social Development Commission of Milwaukee, inspects a home as part of a program to identify and mitigate lead hazards. Matt Campbell/WCIJ

But only about 20 percent of Wisconsin’s young children are even tested for blood lead each year. It’s a mandatory test for those covered by BadgerCare, but most children with private insurance aren’t tested.

Officials say most lead poisoning comes from old paint or soil. Butensen said drinking water is a potential source that often goes untested.

“You can get some paint chips and buy little kits to send it off to a lab and they’ll tell you. You can’t do that with water,” she said.

Rather, said Butensen, lead testing is a complex procedure that the occupants of a home have to do themselves: “They have to do it at a certain time, in a certain way, at a certain, you know, time apart. And I think it’s too complicated for the average person to just say, ‘Go do this.’”

A Widespread Problem That’s Often Missed

Beginning in 2001, the city of Madison replaced all lead service lines that connected buildings to the municipal water supply. That hasn’t happened in other parts of the state. The Environmental Protection Agency loosely estimates that in Wisconsin, 176,000 of these pipes are made of lead.

But Marc Edwards, an engineering professor at Virginia Tech University who led the study of Flint, Michigan’s spike in drinking water lead, thinks that number is probably higher because of lax testing requirements.

“Unfortunately, over the years, water companies have learned how to sample in areas of the cities that have lower lead in water even if they do have lead pipe,” said Edwards.

The EPA’s regulation for lead in public drinking water is called the Lead and Copper Rule. It’s supposed to ensure that Americans are protected from drinking dangerous levels of the highly toxic heavy metal.

But in reality, the rule only requires a fraction of Wisconsin homes on known lead service lines to be tested.

Public water systems serving more than 100,000 customers have to test 100 households per round of monitoring. Those that serve fewer than 100 customers only have to sample five. Plus, Edwards said a single test won’t always give accurate results.

“We have investigated homes of lead-poisoned children where about 20 samples of lead in water have been collected,” he said. “Eighteen of those will look perfectly fine, and then sample 19 and 20 will have a piece of lead in it. Could be hazardous waste levels of lead in that drinking water. And if a child were to consume it, it’d be the same as eating about 10 dime-sized lead paint chips.”

New Pipes Are Tough To Come By

At the same time, the bar for requiring utilities to replace lead pipes is a high one to reach.

A water utility is compliant with the federal law when at least 90 percent of household samples are below the action level of 15 parts per billion of lead. No system-wide remediation efforts are required even if the remaining 10 percent greatly exceed 15 ppb.

For utilities that fall short of that 90 percent mark, they may be required to install or improve corrosion control which involves adding a chemical, such as orthophosphate, to the water to make it less likely to eat away at lead pipes. And determining the water treatment method that works best requires money, ongoing maintenance and specialized knowledge about water chemistry.

Only after corrosion control is deemed ineffective or is rejected will the utility have to begin incrementally replacing its lines until it’s back in compliance.

For professor Marc Edwards, acknowledging that aging lead pipes are a public health concern is the first step to solving the problem.

“You know, those memories are short, the pipes are very long-lived, they’re going to be there a thousand years unless we do something about it,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.