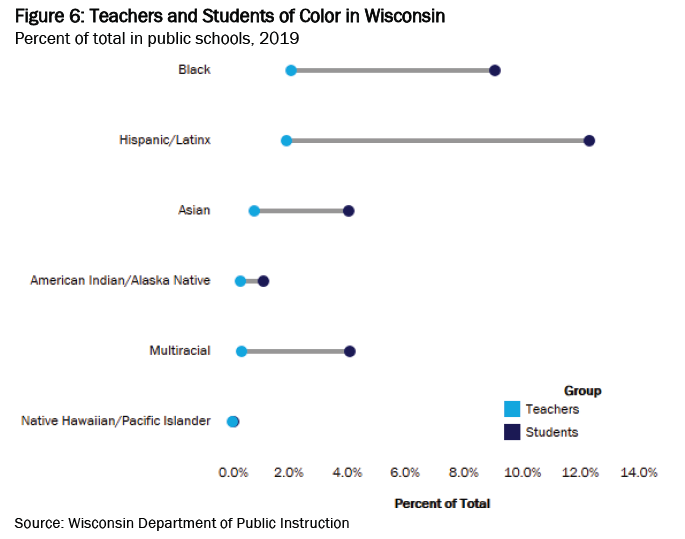

Over the last decade, the gap between the percentage of teachers of color in Wisconsin and the percentage of students of color has widened.

According to a new report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum, the number of students of color in public K-12 schools increased by 28 percent during that period. While the number of teachers of color also increased significantly — by 22.5 percent — because they started as a smaller percentage of all teachers, it’s resulted in a teacher population that’s even less reflective of the student population than it was 10 years ago.

Anne Chapman, the Wisconsin Policy Forum researcher who authored the report, said that pattern holds true for rural areas, suburban districts and towns, as well as the state’s larger cities.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“This isn’t a Milwaukee Public Schools or a Madison schools issue, this is an issue across the state, and this is an issue across different kinds of communities,” she said. “The growth in the gaps was greater in the suburbs, towns and rural areas than it was in the cities.”

Chapman said subsequent reports will dig deeper into the reasons for the persistent racial gap between student populations and the teachers who serve them. She noted in Tuesday’s report that while the various education levels that prepare people to teach have seen a growth in the percentage of people of color in their ranks, each successive level sees a drop-off in Black, Latinx, Native and other nonwhite students — from high school graduation to completion of a bachelor’s degree to passing the tests required to teach in Wisconsin.

“We need to find policies and practices that help more students graduate high school, and more students enroll in and complete college,” she said.

Chapman pointed to years of research that has shown that having a more diverse teaching and administrative staff is good not just for Black and brown students, but also for white students.

Gloria Ladson-Billings, a teacher educator who worked in school districts for years and most recently was on the faculty at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said her own experience bears that out.

“It is important for white children to see people of color as being knowledgeable and authoritative,” she said. “The stuff we are seeing happening in our streets today is, I think, a direct result of young white people saying, ‘I was never really taught to value these people’s lives.’”

She also recalled an African American middle-schooler coming to campus to interview her when she was at UW-Madison.

“And several times during the interview, he would just stop and he would ask the question, ‘You work here?’” she recalled. “And I was like ‘You’re sitting in my office, why do you keep asking me this?’ and he said ‘I didn’t know that Black people could teach above 12th grade.’”

The gaps between the demographics of students and their teachers vary by district, as well as by race. Black students make up just over 9 percent of K-12 students, compared to about 2 percent of teachers. Both Latinx teachers and students have more than doubled their numbers, and increased their overall shares of the Wisconsin school population over the past decade, but the gap between them has widened each year — they currently make up 12.3 percent of students, and 2 percent of teachers.

The gap between the share of Native teachers and students is smaller, but Chapman notes that the lower number overall of Native students in the statewide student population likely hides some districts and individual schools with a very high Native population and very few Native teachers. Likewise, the gap between teachers and students in other racial categories only goes down to the district level, so there could be individual schools where the difference is much more pronounced. The data also does not include private schools.

Margaret Noodin is the director of the Electa Quinney Institute for American Indian Education at UW-Milwaukee, which is dedicated to strengthening American Indian education at all levels. She points out that it’s also not a simple matter of numbers — the diversity of tribal populations in the state means representation goes deeper than the racial categories in the state Department of Public Instruction’s data.

“We should be actually taking enough of a nuanced look to say, where are there schools where there is a high population of Native students, and are there teachers in those schools that match that population?” she said. “Frankly, if you go and get a Cherokee teacher and say ‘Yay, we solved the teaching problem, we’ve got a Cherokee teacher teaching all of these Menominee students,’ that doesn’t actually solve the problem — it’s not someone who speaks Menominee, who experienced termination, who has the knowledge of what it’s like to be Menominee.”

Noodin noted that some policy changes could universally help teachers from more diverse backgrounds jump through the hoops of high school graduation, bachelor’s degrees and teacher certifications — placing more value on education, and providing teachers with financial support both in getting trained to teach and in salaries once they get started, for example.

“We actually would like to see teachers valued, broadly, across society,” she said. “Until we value teachers the way we value CEOs, until we pay the presidents of the college what we pay the coaches of the football team — how much we value that kind of work, and how diverse we allow people to be who enter that kind of work, that’s part of the issue.”

Ladson-Billings echoed that idea.

[[{“fid”:”1290946″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3ECourtesy%20of%20the%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3E%3Cem%3ECourtesy%20of%20the%20Wisconsin%20Policy%20Forum%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”,”title”:”Chart showing the racial gap between students and teachers by locale”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]

“My pie-in-the-sky thing would be that they earn more money, because they should, and that it would be a more prestigious profession,” she said. “Another thing is loan forgiveness — you don’t want someone coming out of school with $100,000 in loans and taking a job that makes $45,000. That doesn’t make sense.”

She noted that African American students carry more student loan debt than their white counterparts.

Both Ladson-Billings and Noodin noted that upping the numbers of nonwhite teachers will require different approaches depending on who districts want to attract.

Noodin pointed to the history of Native American boarding schools, which forcibly removed children from their parents and stripped them of their traditional language and culture to force them to assimilate into white society. That legacy, she said, means Native populations have unique concerns about education that may need to be addressed if schools want to cultivate a pipeline of Native teachers.

“In the U.S., the federal government attempted to do harm to Native communities through education,” she said. “That’s partly why it’s been harder to get Native folks to say, ‘Yeah, I want to go to college, I want to be a teacher, I want to be a professor,’ because it’s been the way their communities have been harmed in the past.”

Ladson-Billings, meanwhile, pointed out that one negative consequence of the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that segregated schools were inherently unequal was the loss of many Black educators, whose schools were closed as Black students were integrated into white schools.

“That was the right decision, but the way we decided to implement that ruling was to fire the Black teachers,” she said. “I think we had generations of African American children who never saw Black educators — when they came through, they didn’t see going into teaching as a viable option.”

She said that’s on top of an array of problems — lower graduation rates among Black students leading to a smaller pipeline of potential teachers, the cost of education and the availability of career options with more prestige and higher salaries, among others — that lead to fewer Black teachers.

Chapman, the Wisconsin Policy Forum researcher, noted that some districts are taking a “grow your own” approach to hiring teachers more reflective of their schools’ demographics. They look for ways to strengthen teacher education, and recruit people like education assistants — also called paraprofessionals — who don’t have the education required for most teaching jobs but are often a more diverse pool, and have a demonstrated desire to work in education and with children.

“The representation (of people of color) is lower among teachers than it is among the general population, so is there something we could be doing to help cultivate a desire and an ability for those people in the communities to be able to enter the teacher workforce? That’s the policy that comes out of that data,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.