State health officials are warning medical providers about a continued increase in congenital syphilis, an infection that affects unborn and newborn babies.

The state Department of Health Services issued a memo to providers, local health departments and tribal health clinics about the need to test pregnant people for the bacteria that causes the infection.

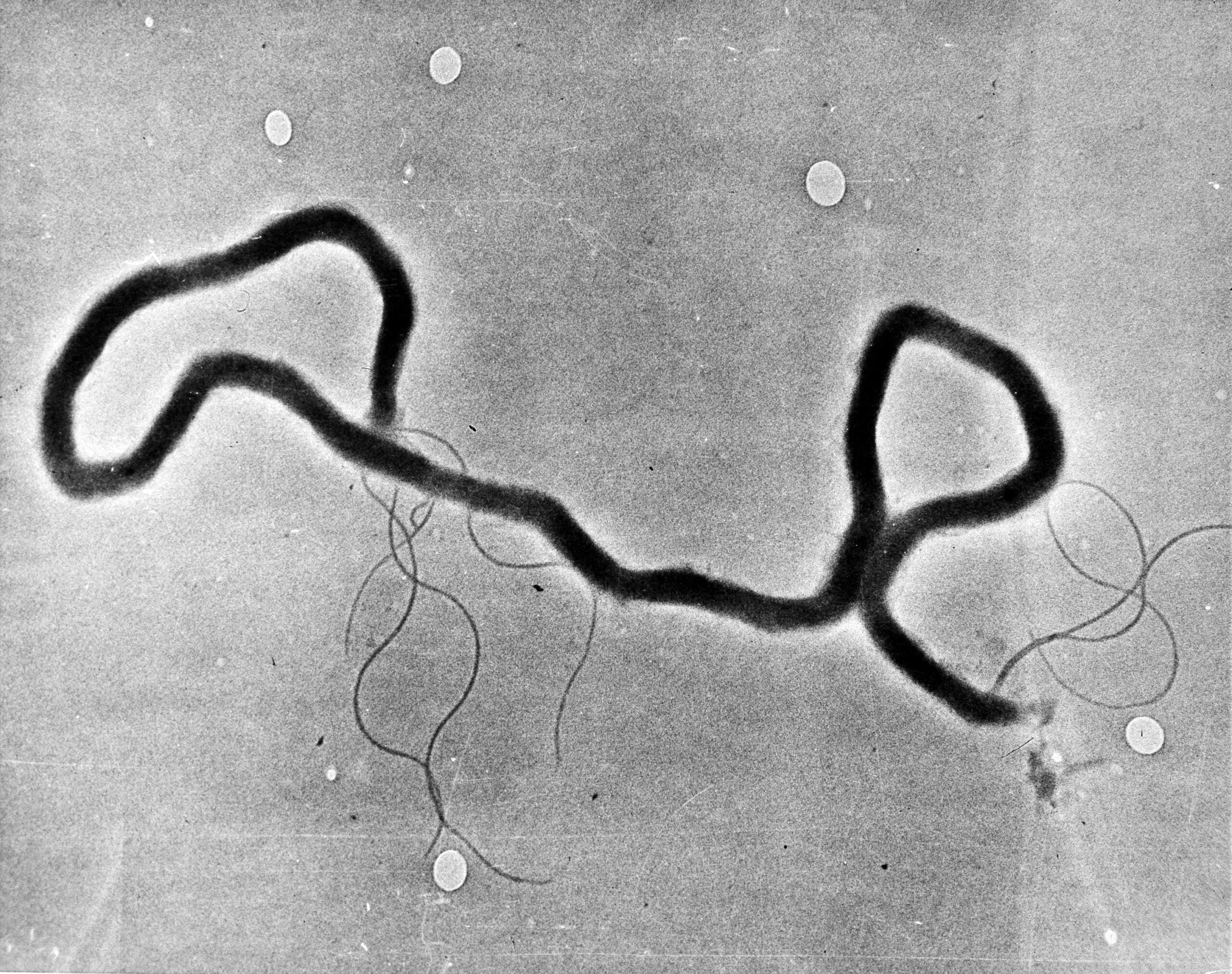

Syphilis is typically spread through sexual contact and is treatable with antibiotics. Congenital syphilis occurs when a pregnant person with syphilis passes the bacteria to their unborn child.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The infection can cause miscarriage or premature delivery and can lead to serious health problems after a baby is born. According to DHS, up to 40 percent of babies with congenital syphilis are stillborn or die from the infection.

The state only recorded two cases of congenital syphilis in 2019. Last year, the total reached 29 cases.

It corresponds with a larger increase in the total number of syphilis cases of all types across the state. DHS recorded 1,916 cases of syphilis in 2022, 19 percent more than the previous year. By comparison, the state reported 585 cases in 2019.

Craig Berger, DHS syphilis surveillance coordinator, said the state has seen a similar number of cases so far in 2023. He said the increase in infections first started in 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down sexually-transmitted infection clinics and testing facilities.

“We did have less testing taking place, therefore there were probably less folks who knew that they had syphilis,” Berger said. “Then there were less ways of getting people treated and finding their partners and getting them treated as well.”

He said people with the infection often don’t recognize the symptoms or can attribute them to something else, like assuming a rash was caused by changing laundry detergent. People with late-stage syphilis typically have no symptoms and the disease can only be identified through a blood test.

While infection rates have increased in all parts of the state, Berger said congenital syphilis has specifically increased in the urban areas of Milwaukee and Madison.

Black people are most affected by the infection, with the Hispanic and Native American population also disproportionately impacted. The state reported that over 65 percent of newborns with congenital syphilis in 2022 were Black. Berger said the prevalence mirrors racial inequities seen in many areas of public health that are linked to the impact of systemic racism and mistrust of health care providers.

In response, Berger said the state is doing more disease intervention work, which includes following up with a person after their case is reported to provide education and trying to locate recent sexual partners for testing and treatment.

Berger said there have also been more cases reported among cisgender women in the state than in the past. He said changing sexual behaviors may be impacting the prevalence data.

“With sexual fluidity, we’re seeing more and more people with multiple partners, multiple gender partners, so it’s crossed barriers in that sense,” he said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that more reproductive-age women are being infected with syphilis nationally. From 2020 to 2021, the most recent data available, the rate of syphilis cases in women ages 15 to 44 increased by 52 percent. The CDC also reported a 30 percent increase in the rate of congenital syphilis cases during that time.

DHS is recommending medical providers increase syphilis testing of all patients, but especially pregnant people. Berger said Wisconsin is one of only a few states that don’t require syphilis testing for pregnant individuals. He said the previous state recommendation was to test for the infection once during pregnancy. But state health officials are now recommending pregnant people receive three tests over the course of their pregnancy to ensure the earliest possible detection.

“With early detection and treatment of it, it’s fine, we can see a baby carried to full term,” he said. “It’s the cases where we don’t find it until birth and then there can be many birth defects that happen, including death.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.