Scott Seyforth has read more than 100 interviews with Carson Gulley.

Not once did the culinary, radio and TV pioneer of the mid-1900s mention how proud he was of his now-famous fudge bottom pies, said Seyforth, a University of Wisconsin-Madison assistant director of residence life at University Housing.

“It’s one of the only things people know him for because for 40 years, it’s the only way almost that university communications has presented him to the public — as in relationship to fudge bottom pie,” Seyforth said recently on WPR’s “The Larry Meiller Show.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That’s not to say Gulley wasn’t proud of his pie or that the university and Madison community don’t adore the dessert. But Seyforth said the iconic chef was most proud of his baked bean recipe.

Perhaps the most extensive written history published on UW Housing’s website about Gulley’s life and the barriers he broke lives under a 2018 article for the ingredients to make the fudge bottom pie.

But the legacy of what Gulley brought to UW-Madison — a legacy that lives on in the form of the refectory he once served being named Carson Gulley Commons — is not Gulley’s complete story.

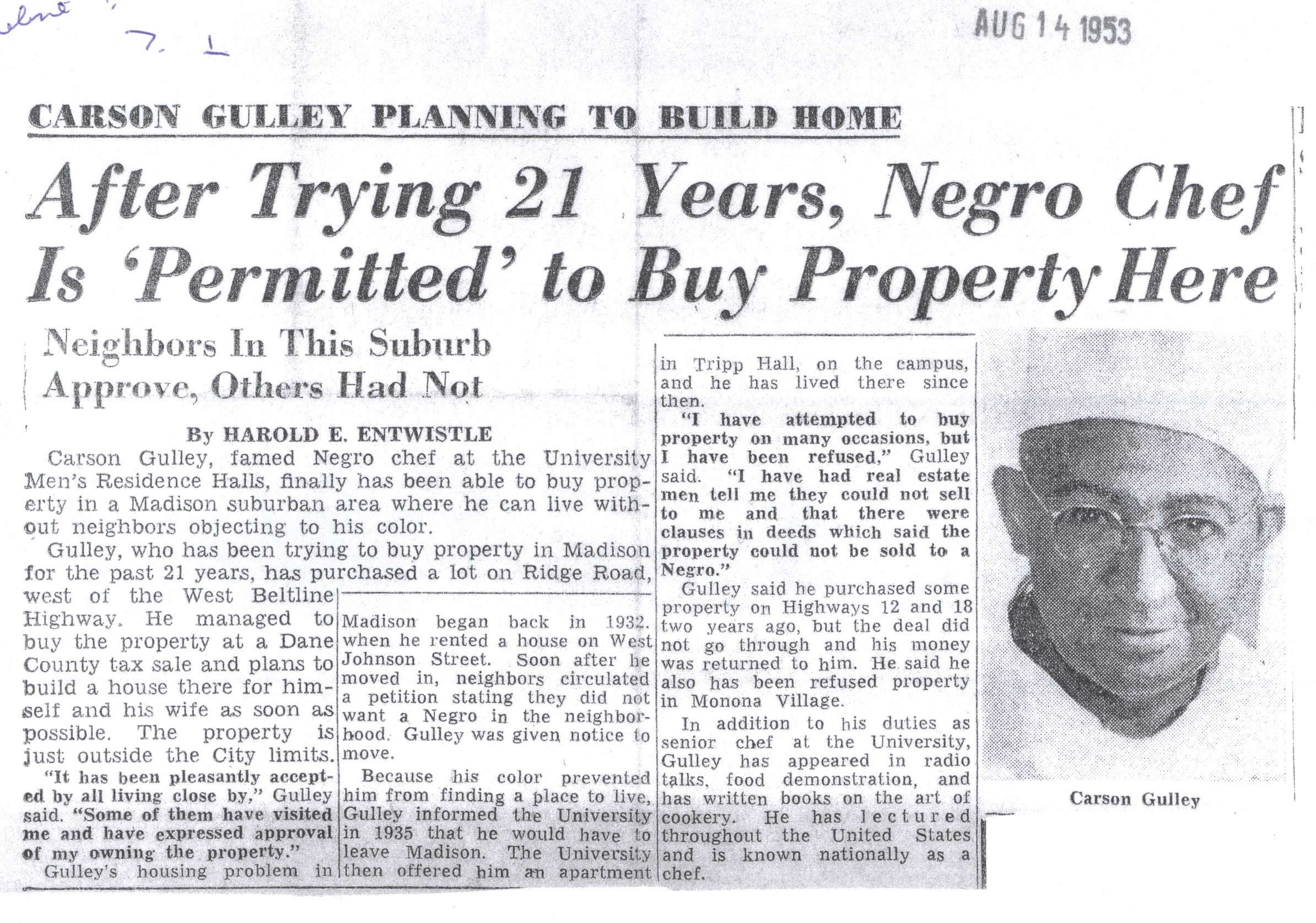

His full life included facing rampant racist and discriminatory practices, from continually being passed over for supervisory roles despite his excellent performance to white neighbors circulating petitions trying to evict him and his wife.

“He continued to fight,” Seyforth said. “This is the part of Gulley’s life that we tend to not tell in Madison — the way that he used his professional and his public stature to challenge the persistent practices of racial segregation and exclusion in that time.”

The harsher realities of Gulley’s story are not absent from university articles or videos about him.

The “About the recipe and its creator” section of the fudge bottom pie page details Gulley’s upbringing with a family of sharecroppers in the early 1900s in Arkansas, his foray into the field of education and his pivot to a career as a chef.

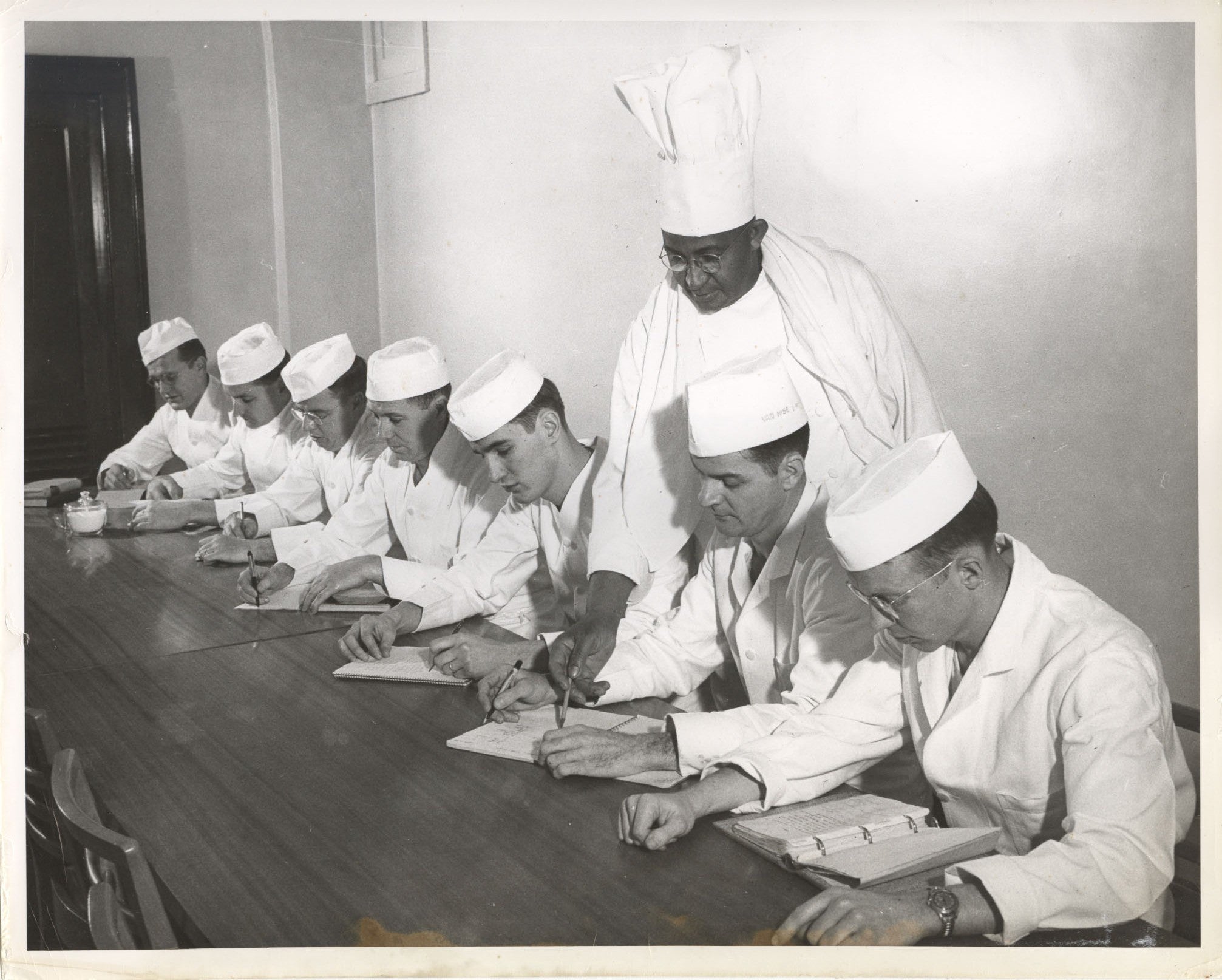

Seyforth said Gulley had to learn his culinary skills on the job because chef training schools largely weren’t open to Black people. So, Gulley worked in a St. Louis hotel before he was hired away to run a boarding school cafeteria, Seyforth said.

But that job only covered September to May. He said Gulley then bounced around more in the summers finding where he could work, from Kansas to Florida to New York.

He also found work one summer in Wisconsin. He was at the Essex Lodge in Tomahawk when a bad storm forced Don Halverson, director of University Housing at UW-Madison, to stop driving north and stay the night.

“Late at night, Gulley made him dinner, and it was amazing,” Seyforth said. “Halverson decided to stay an extra day and a half, and he got to know Gulley and learn what he could do as a chef.”

The two went fishing. They hung out at night, he said, until Halverson asked Gulley if he would come work at the university.

The good fortune intersecting with his hard work didn’t mean Gulley would be free from barriers, however.

“During his early career at UW, Gulley faced segregation and discrimination as severe as in the South,” the pie recipe page states.

Seyforth said in 1926, Gulley “just had a terrible time finding housing.” The small areas in Madison where Black people could find homes were not near the university.

Gulley would find apartments, but that’s when he came up against the petitions from neighbors.

After about 10 years, Seyforth said Halverson offered to “fix this in the only way that he could,” by building Gulley an apartment in the basement of Tripp Residence Hall.

That’s where Gulley lived for the next 20 years, Seyforth said. Later on, Gulley tried to buy property and would have white people meet with realtors on his behalf. But when he and his wife finally showed up to sign paperwork, the deals would fall through because of racial segregation laws.

Ultimately, Gulley in 1954 bought land in the Crestwood housing co-op and withstood a highly publicized vote, 64-30, to stay.

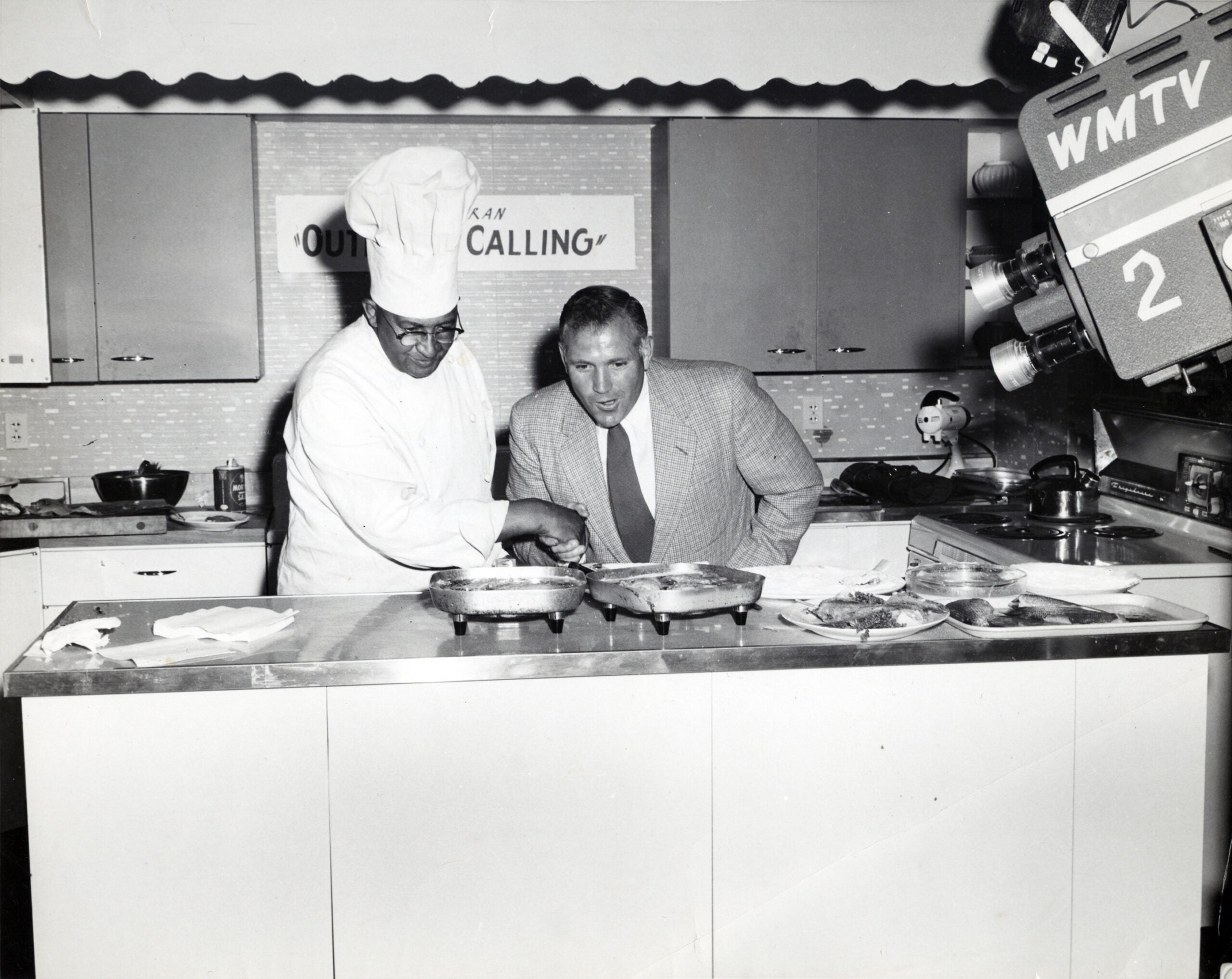

But for all that Gulley brought — his food, his teaching and his TV and radio programs — that doesn’t mean he ended up with what he and others deserved.

“Which isn’t to say that (surviving the vote) was wonderful,” Seyforth said. “They had a cross burned in their yard. They had constant hate mail (and) phone calls.

“They persisted,” he continued. “It didn’t mean that any other people of color moved in. And it did not change the laws in Madison at that time. In fact, Gulley wouldn’t live to see the change of the racial segregation laws in Madison.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.