Jemima Metoxen, Ophelia Powless and Sophia Caulon left home more than 100 years ago.

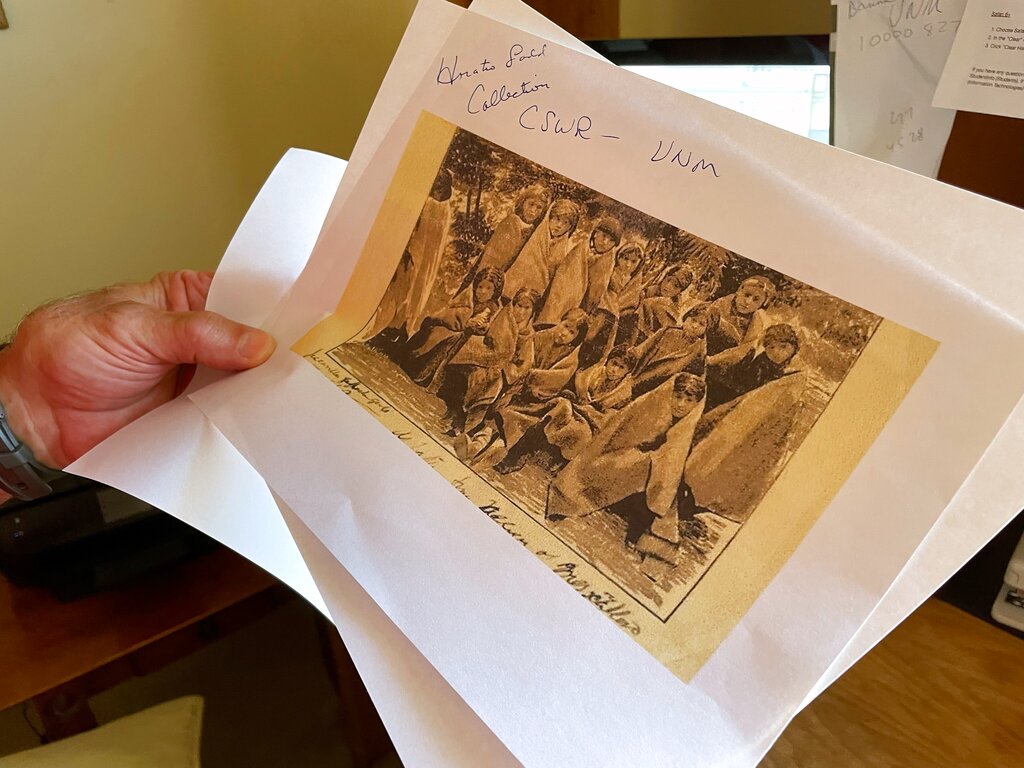

The three Native American girls, members of the Oneida Nation, were among the thousands of children sent to so-called “Indian Schools,” the boarding schools for children designed to strip them of their culture.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

What we know of the girls today is limited to a few surviving records from the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, including single-line obituaries recording their deaths at the school. To the Oneida Nation, they are only a few of the casualties of what Oneida member Bobbi Webster called a “nationwide epidemic” in the 19th and early 20th centuries: the removal of children from their families to attend Indian Schools.

Today, the school’s Carlisle, Pennsylvania site is home to a U.S. Army barracks. And this weekend, as part of an Army project, the three girls’ remains will be returned to their Wisconsin community, where they will be honored and receive burial services.

“The efforts today are to bring them home and to make sure that they rest in peace — and that we bring them home in a manner that our culture and our traditions speak to taking care of those individuals,” said Webster, public relations director of the Oneida Nation.

The girls will receive an honor song at Friday’s 47th Annual Oneida Pow-Wow. On Sunday, remains of Metoxen and Caulon will be buried at the Oneida Sacred Burial Grounds, and those of Powless will be buried at the Holy Apostles Cemetery. Community members will host a public meal following the services.

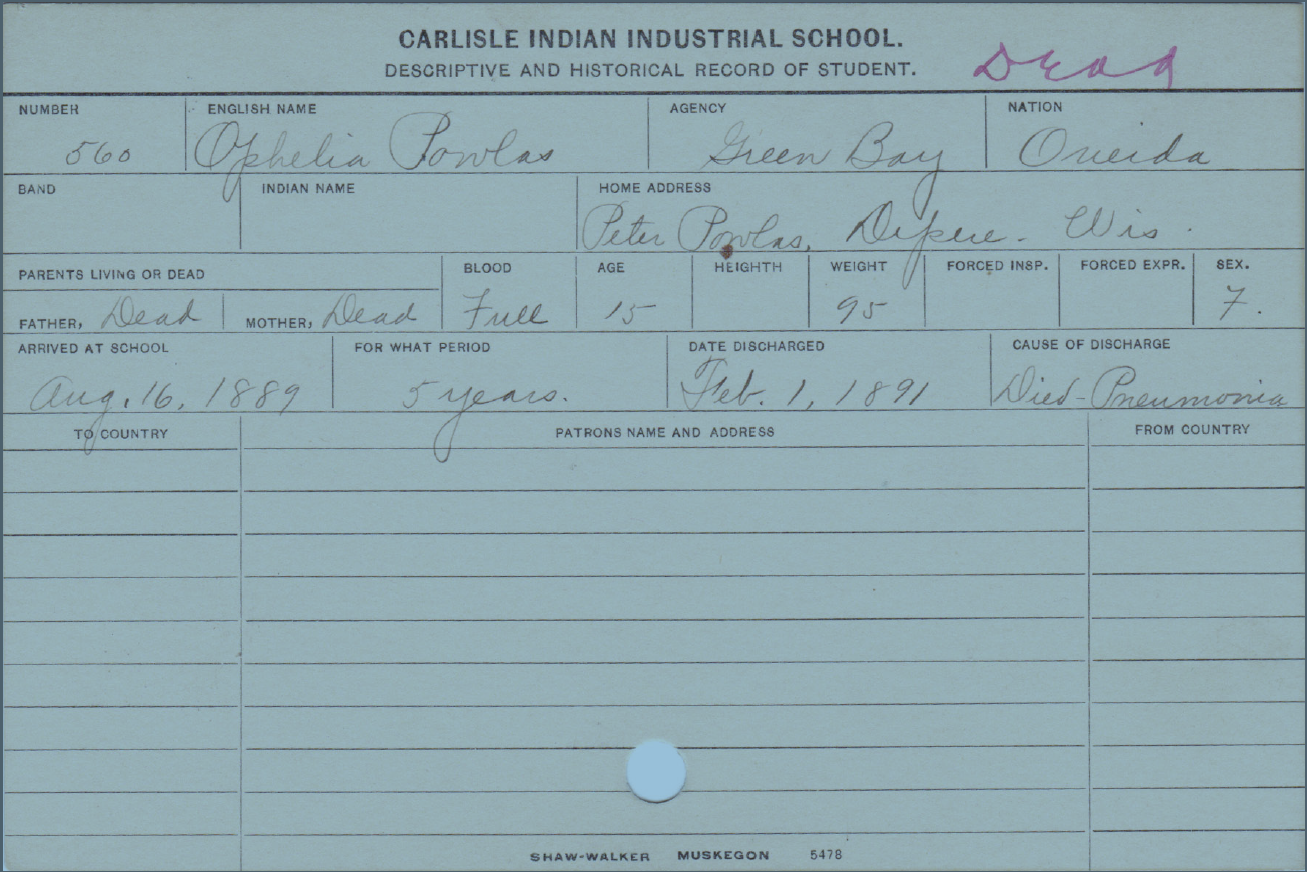

Powless was 16 when she died of pneumonia in 1891. According to her student information card, which spelled her last name “Powlas,” she was an orphan, and weighed 95 pounds when she came to the school at age 15.

An obituary for Sophia Caulon (spelled “Coulon”) called her “one of our nice, good, quiet girls,” and said she was “a member of the What-so-ever Circle of King’s Daughters,” a Christian group. She died of tuberculosis in 1893. She was 18, only months away from graduation.

Metoxen arrived at Carlisle in September 1903. She died in April 1904 of spinal meningitis. She was 16.

Some Native Americans were sent by their families to the military-style boarding schools with the goal of helping them assimilate with Americans of European descent. But other students were forced by government officials to go. More than 10,000 Native American children attended the Carlisle school between 1879 and 1918.

Webster said it was not an environment that allowed all students to thrive.

“They were lonesome,” she said. “They were taken away from their families. They were far from home. They were in a complete turmoil in terms of what they had been brought up in.”

Webster said research by the Oneida Cultural Heritage and the Oneida Enrollments departments found that 109 Oneida community members were identified as descendants of Oneida tribal members who died at the Carlisle school.

Kirby Metoxen, a member of the Oneida Council, said in a statement that the reinterment of the students’ remains brings mixed emotions.

“We are happy that we can bring our family members home so their spirits can rest in peace with their families, but we are also quite saddened by the fact that these are only a few of the many of our ancestors who have not been laid to rest in their homeland with their families,” he said.

“This remains an unsettling era in our history,” Metoxen said. “When children, some as young as 3 years old, were taken from their parents in attempts to assimilate them and eventually take away their language, their culture and their souls.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.