At least 500 Native American children died while being forced to attend federal Indian boarding schools between the years 1819 and 1969, according to a report released Wednesday by the U.S. Department of the Interior. Eleven of those schools were located in Wisconsin.

At an emotional press conference on Wednesday, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland spoke about the troubling legacy of these schools and their lasting impact on Native communities, as well as on her own family.

“When my maternal grandparents were only 8 years old, they were stolen from their parents’ culture and communities and forced to live in boarding schools until the age of 13. Many children like them never made it back to their homes. Each of those children is a missing family member, a person who was not able to live out their purpose on this earth because they lost their lives as part of this terrible system,” Haaland said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Since launching the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in 2021, Haaland and her department have worked to acknowledge the extent and impact of the boarding school system.

The new report, spearheaded by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland, is the first-ever inventory of federally operated Indian boarding schools. Using existing historical records, the study identified 408 schools across 37 states, some of which are still in operation today. Each of these schools enrolled as many as 1,200 students.

About half of the schools were supported by religious institutions, and many might have utilized funds that were held in Tribal trust after the forced cessation of American Indian territories.

According to the report, burial sites — both marked and unmarked — were found at 53 of the schools, but that number is expected to increase as the investigation continues. A followup report, bolstered by a $7 million federal investment, will identify the location of student burial sites and attempt to confirm the identities and tribal affiliations of children who attended and/or died at these schools.

Newland said it will also approximate the federal funding used to support these schools and further examine the long-term effects of this system on tribal communities.

“From the breakup of families and tribal nations to the loss of languages and cultural practices and relatives, this has left lasting scars for all Indigenous people,” Newland said. “This report is not an end … It’s a beginning. It marks one of the first steps on the road to help begin a healing process in this country.”

‘I didn’t know anything about who I was’

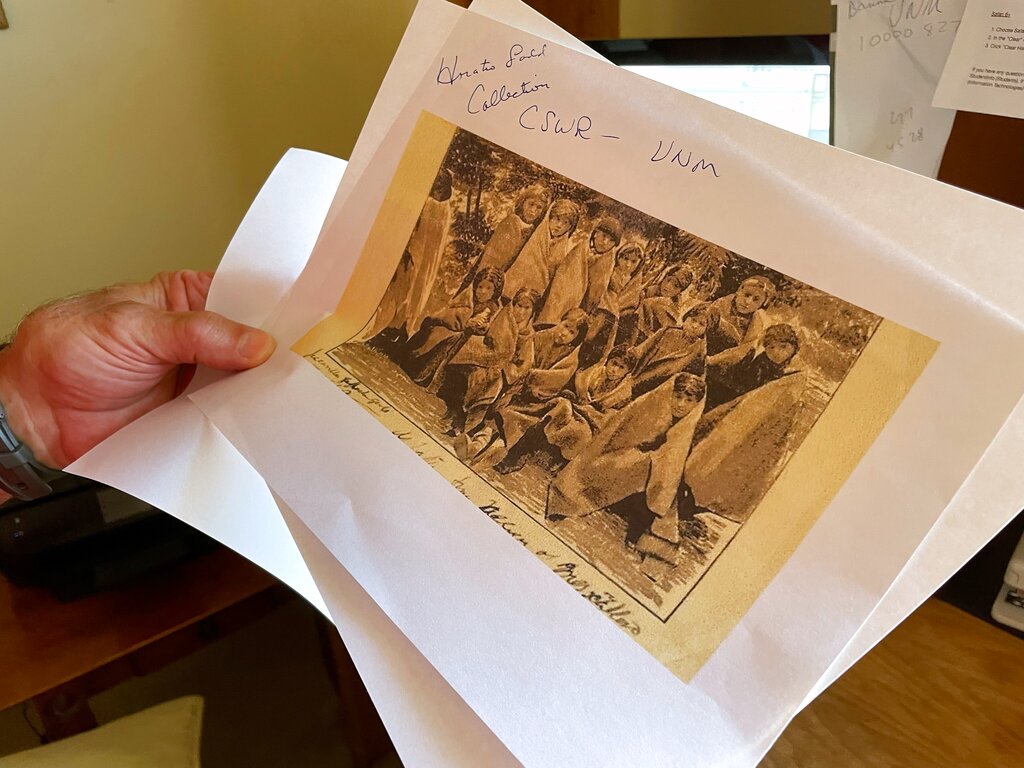

Starting with the 1819 passage of the Indian Civilization Act through 1969, the federal government implemented policies establishing and maintaining Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose was to culturally assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children by forcibly removing them from their families, communities, languages, religions and cultural beliefs. The children who attended these schools often endured physical and emotional abuse and, in some cases, died.

According to the report, schools utilized “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” to assimilate Native American children. This included military drills, changing students’ names, cutting their hair and discouraging or preventing the use of Native languages, religion and cultural practices.

James LaBelle Sr. attended Indian boarding schools from the age of 8.

“I learned everything about European American culture, history, language, civilizations, math and science, but I didn’t know anything about who I was as a Native person,” said LaBelle at Wednesday’s press conference.

LaBelle is vice president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, which partnered with the Department of the Interior to collect records and testimony about these schools.

“Our children had names. Our children had families. Our children had their own languages. Our children had their own regalia, prayers and religion before Indian boarding schools violently took them away,” said Deb Parker, the coalition’s CEO.

She went on to provide emotional testimony about living near the Tulalip boarding school in Washington state and wrestling with the truth of what happened there.

“We knew there was a little jail cell. We knew that the basement was for when the kids were crying and wanting to go home. We knew that children didn’t get to go home. They were missing,” Parker said. “We know that one of our young girls was sent to the basement and she was chained to a heater and beaten daily.”

11 schools were located in Wisconsin

In 2021, Gov. Tony Evers signed an executive order apologizing for the state’s role in supporting Indian boarding schools and committing to work with the Interior Department on its investigation.

Wisconsin had at least 11 boarding schools, including in Wauwatosa, Green Bay, Hayward, Keshena and Bayfield.

Many more children were sent to schools in other states. Over 400 children from the Oneida Nation were taken to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where some of them died.

In 2019, the remains of three Native American girls were disinterred and returned to their homes in Wisconsin.

Locating more of these burial sites and returning remains to their homes will become a main focus in the next phase of the DOI investigation.

“Our children deserve to be found. Our children deserve to be brought home,” Parker said. “We are here for their justice and we will not stop advocating until the United States fully accounts for the genocide committed against Native children.”

‘We must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past’

For many advocates, identifying these schools and burial sites is just the first step.

Being cut off from one’s people and culture, LaBelle said, has left intergenerational scars in Native communities, resulting in disproportionate rates of suicide, substance abuse, incarceration, domestic violence and foster care in Native communities.

“One of the best things that we can do is to protect Indian families today and to keep Indian kids with their families and in their communities,” Newland said.

He said this means protecting the Indian Child Welfare Act, but also supporting policies of cultural revitalization to revive Native languages, cultural practices and traditional food systems.

“It’s going to require some sort of resources to help put families together,” Newland said.

As part of the broader initiative, Haaland announced on Wednesday the launch of “Road to Healing,” a year-long, cross-country tour to help Native communities and survivors of federal Indian boarding school policies share their stories and access trauma-informed support. The tour will also document a permanent oral history of the school system and its lasting impact.

“Recognizing the impact of the federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning,” Haaland said. “To address the intergenerational impact of federal Indian boarding schools and to promote spiritual and emotional healing in our communities, we must shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past. Today, we take a critical step forward in that work.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.