The Madison Metropolitan School District has formally acknowledged that their schools sit on land originally inhabited by Ho-Chunk people. The student-led initiative is part of a broader effort to incorporate more Indigenous history into the district’s curriculum.

MMSD and Ho-Chunk leaders held a land acknowledgement ceremony Monday to commemorate the occasion.

“Government-sanctioned institutions have been responsible for much of the trauma to First Nations families, and that is why MMSD is proud to lead this effort towards healing the wounds of the past, beginning today,” said MMSD Deputy Superintendent Carolyn Stanford Taylor.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Indigenous invisibility

The move comes after Indigenous students said they felt invisible in their schools.

Madison West High School junior Isabella (Isa) Saiz is a member of the Unis Ponca Tribe and part of her school’s Native American Student Association, or NASA.

“Indigenous invisibility is just the absence of knowledge of Indigenous peoples and the land that we are standing on,” Isa said. “As a student, I’ve grown up seeing errors in the curriculum — some nations go by different names now and they still have the old names that they find offensive.”

And Indigenous students at Madison East High School have experienced the same thing. Junior Marena Fox Baker is a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes and co-chair of her school’s Native American Students Association.

“Indigenous students in our community wanted to feel safe, seen and acknowledged,” Marena said. “Throughout my time in the district, I saw little to no representation of Indigenous people in my schools. The art on the walls did not reflect us, nor did the curriculum that was taught.”

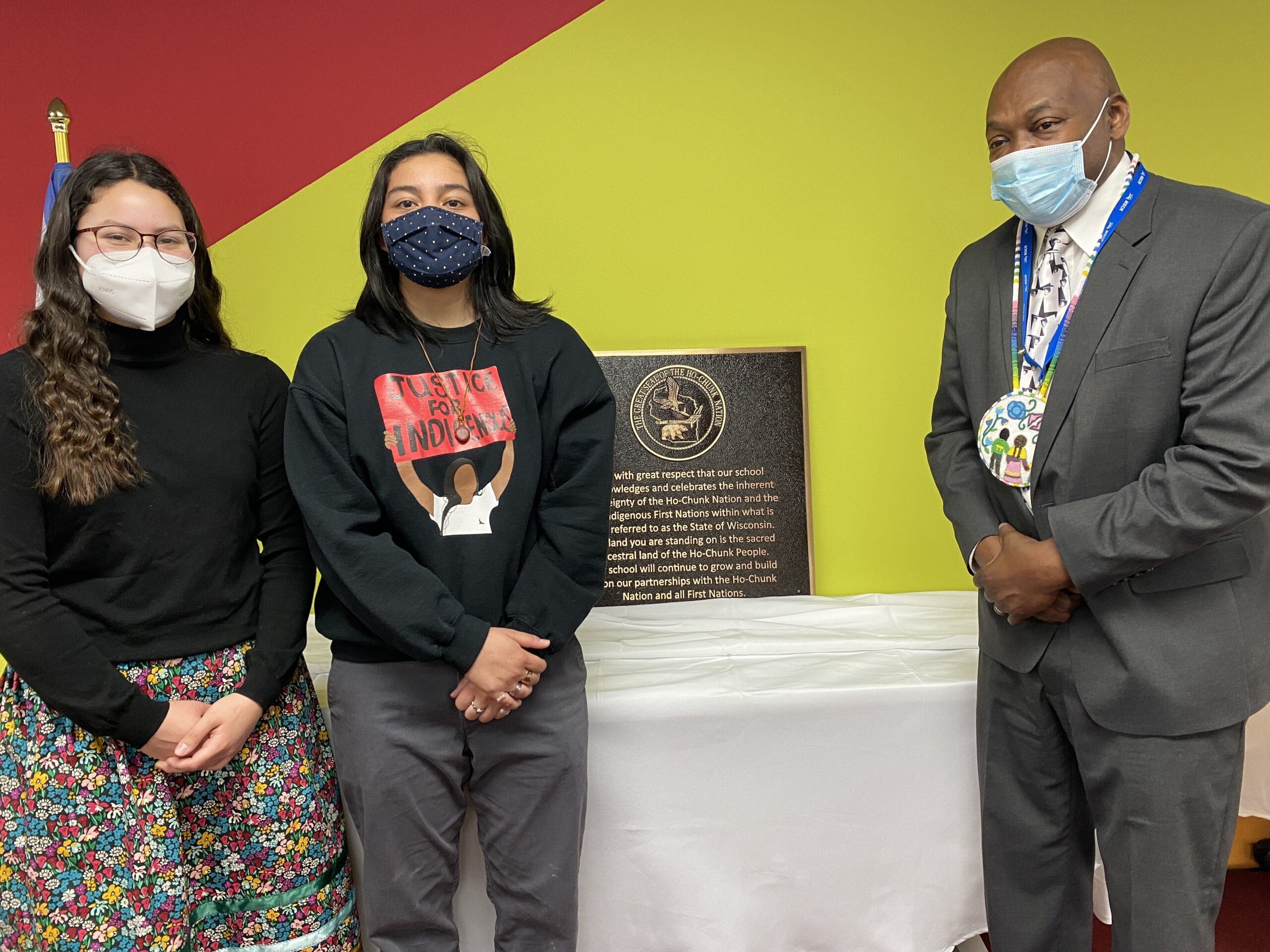

When Isa and Marena saw the University of Wisconsin-Madison issue a land acknowledgement in 2019, they got the idea to install plaques at each of their high schools.

With the Ho-Chunk Nation’s blessing and support from the district’s Native American parents committee, the students approached MMSD with the idea. Superintendent Carlton Jenkins was all for it.

“He supported the students, supported us and actually encouraged us to go much bigger,” said Sean Saiz, Isa’s father and a member of the parent committee. “He was like, ‘Just don’t do East and West, let’s look at this as a bigger picture … do all the schools.”

Over the next three years, MMSD committed $90,000 to install plaques at all 52 schools as well as district offices.

Isa and Marena, along with fellow NASA members, will help schools plan student-led dedication ceremonies, starting with the district’s elementary schools.

“I’m really excited to talk to them,” Isa said. “I’m glad that they can have this representation started at a younger age than we did.”

More than a plaque

While more and more public institutions are issuing land acknowledgements, the move is sometimes criticized as performative. But Marena, and many of the speakers at Monday’s ceremony, said the plaques are just the beginning.

“In one way, this is groundbreaking because no school district (in Wisconsin) has ever done something like this. But on the other hand, it is just the beginning,” Marena said. “The real work is changing the curriculum, building relationships with the Tribal Nations of this state and ending Indigenous invisibility in the schools so that future generations of Indigenous students can see themselves in all parts of education.”

In addition to the plaques, MMSD committed to providing teacher training and curriculum with more representation of Indigenous history and culture. Despite the state statute requiring American Indian studies to be taught at all public schools, Jenkins said the portrayal is not always accurate.

“Our history hasn’t always been pretty. We have to acknowledge that,” Jenkins said. “This is the beginning of us looking at acknowledging wrong done and a path forward. It doesn’t end with a plaque. It begins with a plaque.”

‘The path that my ancestors once walked’

The area we now call Madison was known as Teejop, or “four lakes,” by the Ho-Chunk people, who inhabited the region for thousands of years until they were forcibly removed in 1832.

Ho-Chunk Nation President Marlon WhiteEagle said Indigenous leaders often feel obligated to explain this history to non-Native people. But he said teaching Indigenous history in schools could ease that burden and ensure that everyone understands Native history as part of Wisconsin history.

“It’s a really great step in the right direction,” WhiteEagle said. “For future leaders of the Ho-Chunk Nation, it’s going to help us down the line that we won’t have to start from ground level.”

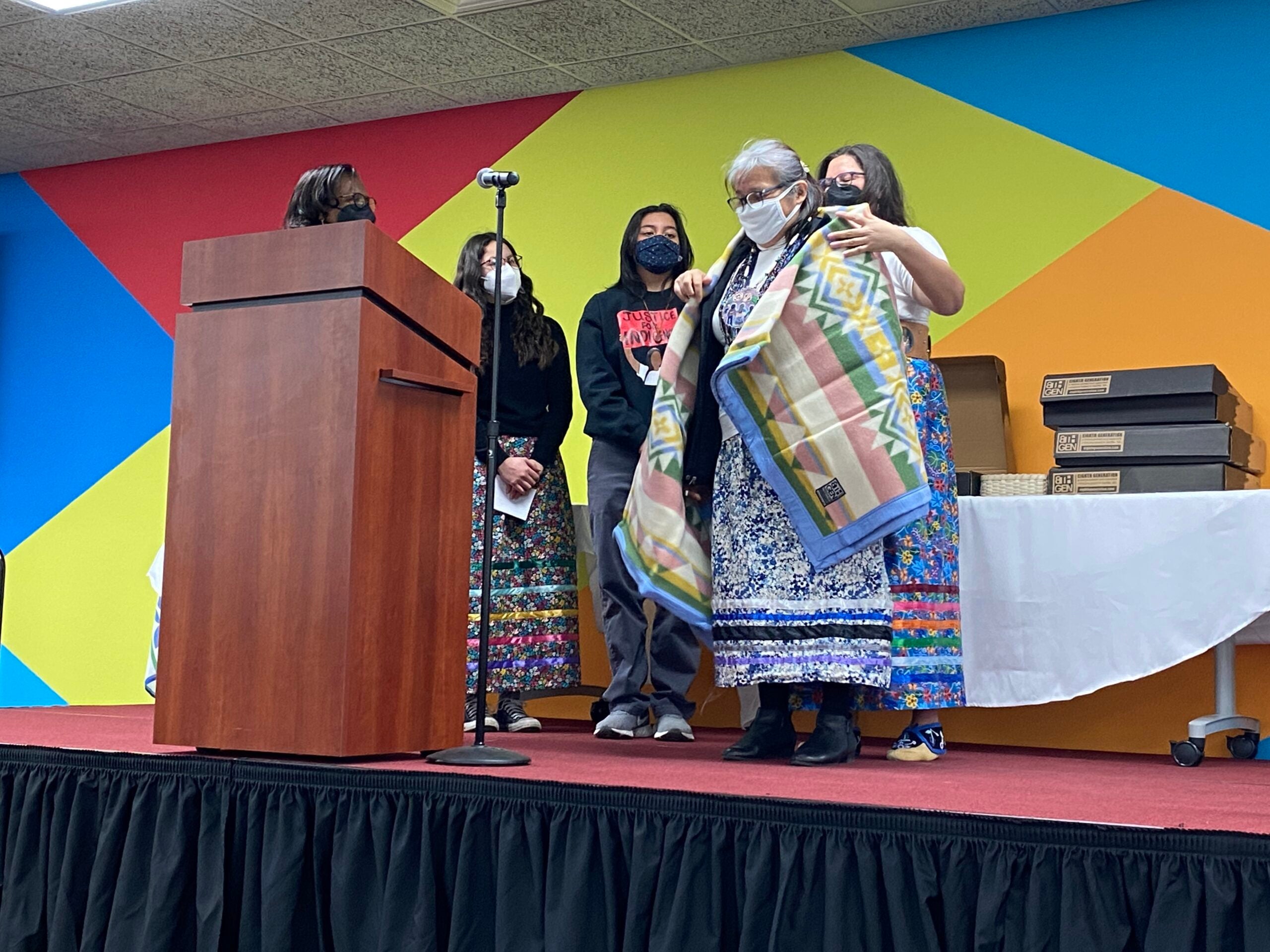

Monday’s ceremony, which included drumming, food and an exchange of gifts, was emotional for Tara Tindall, the district’s Native American Teacher Leader and a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation.

“I’m thinking about my ancestors,” Tindall said. “(They) have been removed over and over and each time our ancestors returned on foot or by boat because of the love and dedication to the land.”

As much as this land acknowledgement initiative was led by youth, the ceremony honored those who came before with speeches from Ho-Chunk elders like Janice Rice.

“Each day when I’m here in this community, I’m always happy and cheerful because my feet are walking the path that my ancestors once walked,” Rice said. “When I see the birds and I hear the songs and see the waters of the Teejop area, I feel blessed and I feel comforted and I feel happy because I’m walking the lands that my grandparents and my great, great-grandparents walked.”

Land acknowledgement resources

- Wisconsin First Nations has a Tribal lands map of Wisconsin and collection of resources for teaching about American Indian history and culture.

- Native Land has a similar interactive map that shows tribal land across the world.

- The League of Women Voters of Wisconsin has compiled a Land Acknowledgement Guide for institutions wanting to take this step.

- UW-Madison assistant professor Kasey Keeler is leading the project, “Mapping Dejope: Indigenous Histories and Presence in Madison,” which will be a digitally accessible Indigenous history tool.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.