Around noon on an overcast April Election Day, dozens of canvassers returned to a second-floor conference room of the Greater Spring Hill Missionary Baptist Church on Milwaukee’s North Side.

They were dressed for the weather: Layers, winter hats and a few with ponchos. Within an hour, they would be back out in neighborhoods and knocking on doors. Walking a careful line between helpful resources and yet another person asking them to vote for the sixth time in less than 16 months.

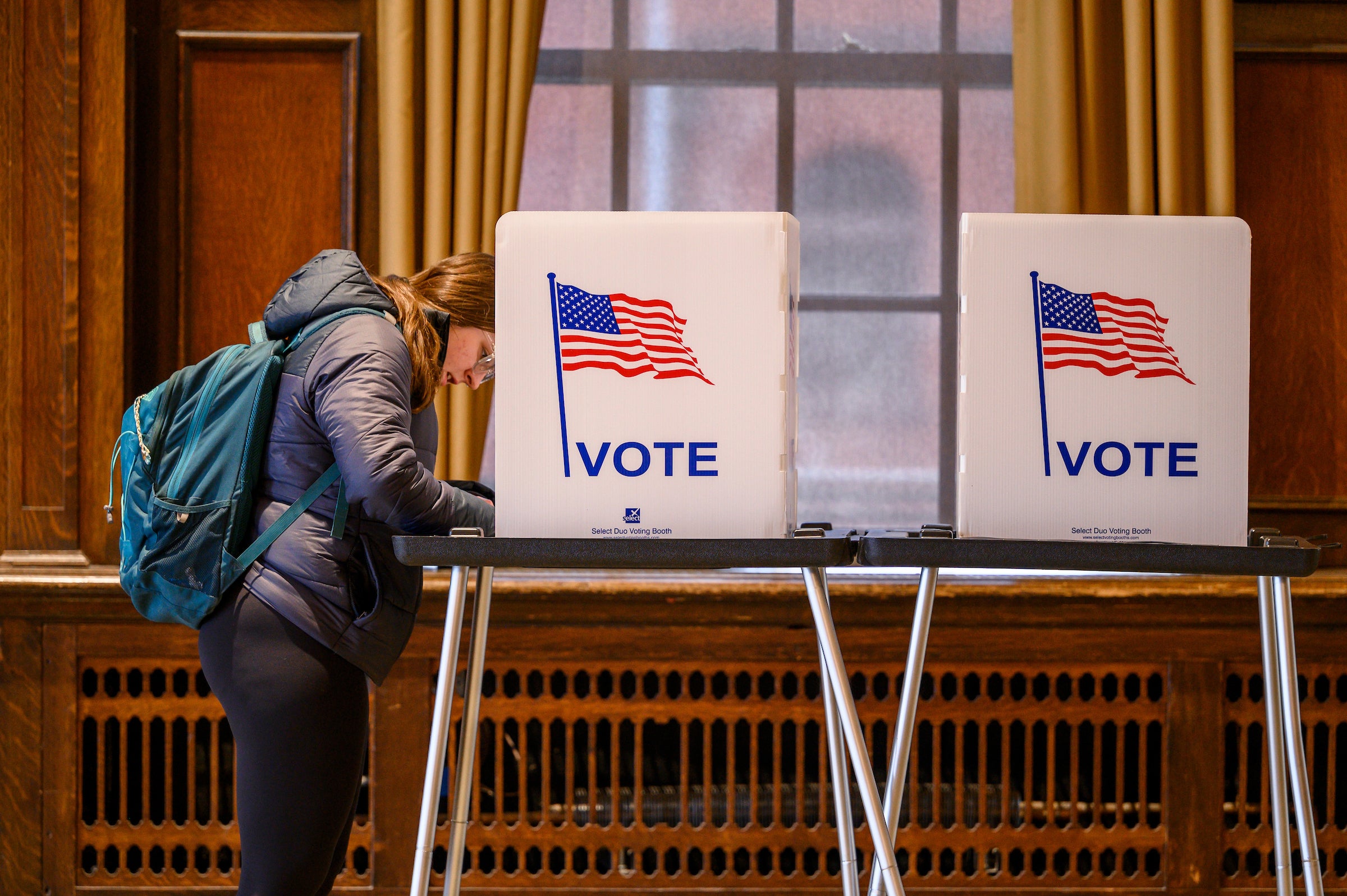

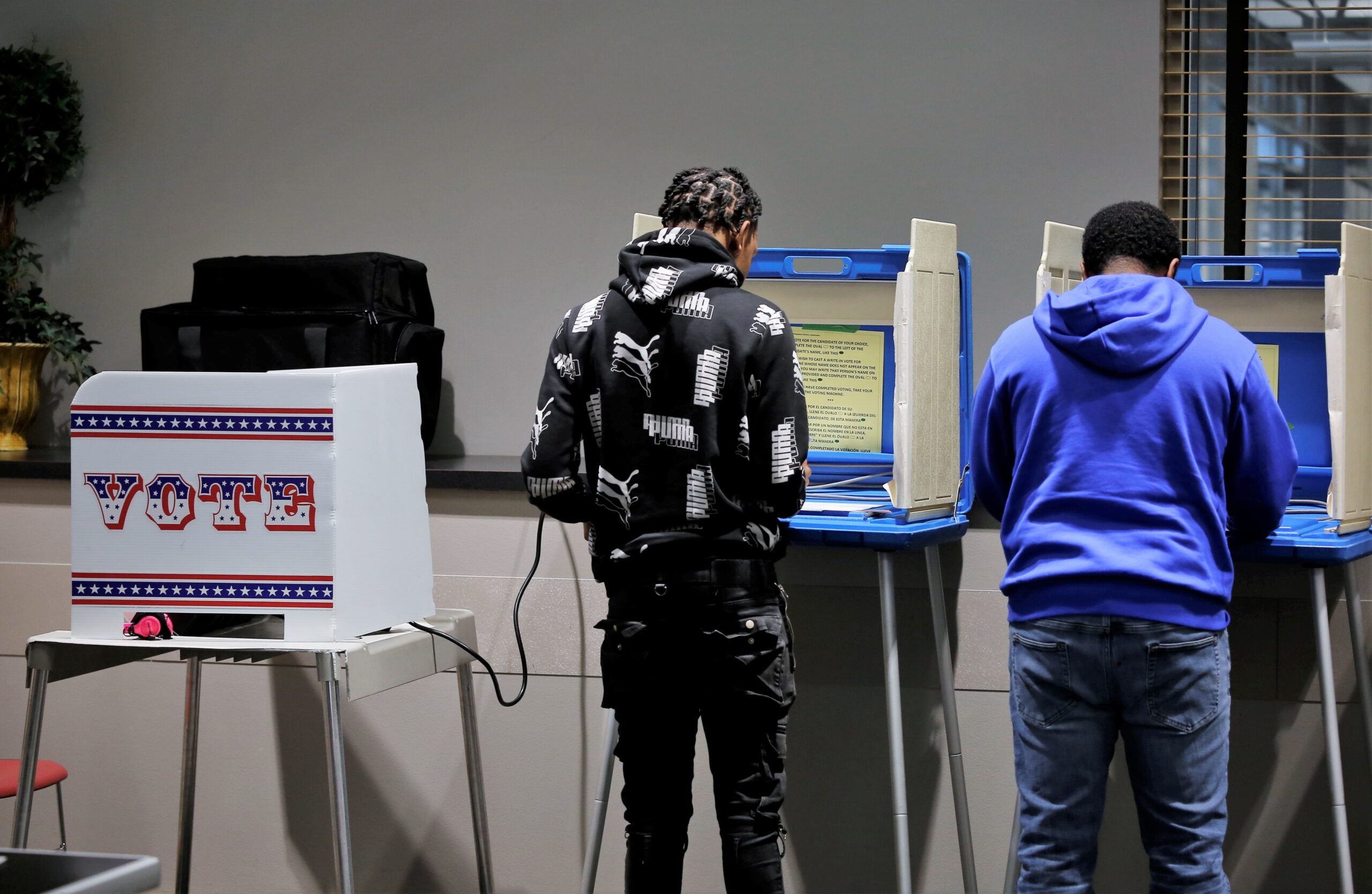

The gathering of Black Leaders Organizing Communities represents a bulwark against an alarming trend in Wisconsin electoral politics: The state has transformed from one of the easiest places to cast a ballot 30 years ago to one of the most difficult. That trend is particularly pronounced among Black and Latino voters, according to recent research.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

If BLOC’s canvassers were tired of talking about elections, executive director Angela Lang told them to imagine the fatigue voters felt.

“We had four elections just in 2022. Four,” she said. “The last one was in November. We slept for like a day, and we’re back at it. If we were doing all of this, imagine being a voter that’s not involved and engaged.”

There’s evidence the increased difficulty voters face compounds the election fatigue.

“If we believe in this experiment of democracy, one of the basic tenets of it … in our current iteration is that everyone who is a citizen at this point has the right to engage with the process,” said Andrea Benjamin, an African American studies professor at the University of Oklahoma who has researched and written about race and politics.

“And we shouldn’t be doing anything that makes that right harder to exercise.”

How it’s gotten more difficult to vote in Wisconsin

For nearly 20 years, Wisconsin was a model for making the voting process easy, with the state’s same-day registration a major factor, according to the Cost of Voting Index. In 1996, Wisconsin ranked fourth among the 50 states.

In 2022, Wisconsin was among the most difficult places to register and vote, ranking 47th.

The Index, started by researchers at Northern Illinois University, ranks each state using 33 different variables, with registration deadlines carrying the most weight. As other states began to adopt measures already present in Wisconsin, such as same-day voter registration, Wisconsin’s ranking dipped slightly, but remained in the top 10.

Then Republicans took control of the Legislature and governor’s office after the 2010 election and implemented several measures that made voting more difficult. They extended residency requirements, shortened the time frame for early voting, increased residency requirements from 10 to 28 days and enacted the state’s voter ID law, which after several court challenges took effect in 2016.

“As soon as Wisconsin adopted that, it really caused the state to drop in accessibility,” said Michael Pomante, a Jacksonville University political science professor and co-author of the Index. He added that the drop suggested Wisconsin voters faced a “significantly” different landscape compared to other states.

More recently the state Supreme Court disallowed ballot drop boxes — even as some states expanded use — pushing Wisconsin even further down the list.

“It needs to be said or at least noted to Wisconsinites that their voting has become significantly more difficult for their voters over the years compared to other states,” Pomante said. “I mean, they are one of the states that has seen the most dramatic shift in the difficulty of voting over the last two decades.”

Republicans enacted the voter ID law and other restrictions in the name of election security. Then-Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, described the voter ID law specifically as making it “easier to vote and harder to cheat.”

There’s no evidence the laws have significantly affected election fraud.

From 2012 through 2022, there were 48 general, primary and special elections in Wisconsin. Prosecutors brought only 192 election fraud cases, or 0.0006% of all votes cast, Wisconsin Watch previously reported. And only 40 cases dealt with fraudulent actions like double voting or voting in the name of a dead person. The data didn’t show that the new laws had reduced the number of cases, the majority of which related to voting, often by mistake, by those on probation for a felony conviction.

And while it’s possible the laws make it harder to cheat in ways that elude prosecution, they also make it harder for many to vote.

Complicating matters over the past decade: changes to law or procedure coming right before an election, usually as the result of a lawsuit. That’s one of the biggest challenges for election administration, said Claire Woodall-Vogg, executive director of the Milwaukee Election Commission.

Those late changes, along with lack of voter education funding makes matters more difficult, she said, adding that groups like BLOC can help fill those gaps.

Woodall-Vogg said she’s “cautiously optimistic” that things could improve after last month’s Supreme Court win by Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Janet Protasiewicz, which ended 15 years of conservative control of the state’s high court.

“But I will also say it’s cautious,” she added, “because the length of time it takes to get a lawsuit there would again come right in the middle of a presidential election year.”

Additional barriers for Black and Hispanic voters

Barriers to voting disproportionately affect certain racial groups, according to research from UW-Madison journalism and mass communications professor Michael Wagner.

Black voters spent about 9 minutes getting to the polls during the 2018 midterm election, compared with about 6.5 minutes for non-Black voters, the research found. Researchers also found that Hispanic voters spent about 11 minutes in line, more than twice the wait for non-Hispanic voters.

Additionally, they found that Black and Hispanic voters were less likely to use early voting measures, which could ease those time burdens.

In researching the 2022 midterm election, Wagner’s team found Black voters spent 10.8 minutes getting to the polls and 15.6 minutes waiting in line. For white voters, those times were 6.8 minutes and 7.7 minutes.

“It’s really a tale of two states. On the one hand, Wisconsin has incredibly high voter turnout. We’re always in the top three,” Wagner said, adding that same-day registration and tradition of civic engagement help. “But things are clearly getting worse for Black, Hispanic and lower income voters.”

Closed polling locations and continued underfunding of elections could help explain growing times from 2018 to 2022, he said.

The researchers who maintain the Cost of Voting Index have linked increased difficulty and a drop in voter participation, but impact varies between groups.

“It actually disenfranchises the undereducated and the lower socioeconomic populations more,” Pomante said. “But if we were to strip those things out and were just looking at racial features, when states have made voting more difficult, it actually spurs Black voters to come to the polls more.”

One reason for that might be the role of community organizers, Pomante said.

Benjamin, the University of Oklahoma researcher, agreed.

“I think that these local organizations … they’re priceless,” she said. “I mean, it’s just worth everything because they have the community’s trust. They have a reputation. The community wants to earn those people’s trust and show that they are also good stewards.”

Wisconsin’s increasingly divisive and contentious politics may also help turnout, Wagner said.

“More people see it as valuable to have their voice heard on Election Day,” he said. “Even if it’s harder, many people still show up.”

Current proposals to address voting issues

Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, proposed a range of voting-related changes in his most recent budget proposal that would elevate the state’s Cost of Voting Index ranking.

Pomante said automatic voter registration has propelled many states toward top rankings. Evers has proposed that the Department of Transportation provide identifying information to the Wisconsin Elections Commission so it can automatically register eligible voters. The proposal also allows people to opt out.

The governor also proposed removing restrictions on how early a voter can return their absentee ballot and lowering the residency requirement from 28 days to 10 days. Evers’ budget also includes changes to the type of ID technical college or university students can use and would restore previous requirements that high schools be used for voter registration, something Republicans ended in 2011.

The budget proposal also included additional funding for local election officials and would allow election workers to start processing absentee ballots before Election Day, a measure that would speed up ballot counting. Republicans removed all those and hundreds of other measures from the budget bill during the first votes in the process Tuesday.

Last year, Evers vetoed a number of election-related bills passed by the Republican Legislature. They would have prevented a voter’s friend or family member from returning their absentee ballot, required clerks to verify voters are U.S. citizens, and given the Legislature control over guidance to clerks from the Wisconsin Elections Commission.

State Sen. Duey Stroebel, R-Saukville, said that if there are issues with the time it takes voters to cast ballots, those are “the fault of local municipalities failing to address the needs of their communities.”

“This trend of higher participation holds up across nationwide elections since passing Voter ID,” he said. “Wisconsin voters routinely rebut the premise of voter disenfranchisement through their actions.”

How BLOC and community organizers find solutions

BLOC doesn’t plan to put politics on the shelf until the 2024 spring primary. Politics and voter education is baked into everything it does, Lang said.

“If we’re having conversations in the field about what does it look like for the Black community to thrive, nine times out of 10, those responses have a political connection, whether it’s the city budget that’s going to come out this fall or it’s the state budget,” she said weeks after the election.

“And so there’s so many different ways that civics plays a role indirectly that people may not necessarily see, but every single aspect of our lives has been politicized.”

BLOC reaches voters by building trust. It intentionally set up its headquarters in the 53206 ZIP code, among the most-incarcerated places in the state. BLOC’s members grew up in the community and share the same experiences as the people whose doors they knock on.

They see voters walk into their polling place carrying BLOC literature handed out or placed in doors.

But it wasn’t always like this, Lang said, recalling the group’s first election in November 2017 when residents viewed them like just another group dropping in. They could see through the “transactional electoral organizing” done time and time again by groups parachuting in for the runup to an election.

Attitudes toward the group changed once people saw that they didn’t leave.

“The team (here at BLOC) came up with this idea last year to do monthly neighborhood cleanups as a way to engage residents around other issues and do something that’s beautifying the community,” Lang said. “I think by just having a constant presence allows us to be those trusted messengers.”

Three weeks after the April 4 election, BLOC’s second-floor conference room was once again filled with dozens of people, some of whom endured the rain to canvas on Election Day. But they weren’t there to talk about the next election or even voter registration.

The meeting was about plans for community wellness programs.

It may be the electoral offseason, but BLOC has plenty of work to do.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.