As a member of the honor roll, Morelia Blanco was invited to go on a class field trip to Washington, D.C. when she was in eighth grade. She hadn’t left Milwaukee since she was a toddler, and she was excited, she said. But ultimately, she wasn’t allowed to go.

“No tenemos papeles,” her family told her. We don’t have the papers.

Blanco didn’t really understand what it meant to be undocumented until she was 16 and hoping to get her first job at a yogurt shop in the mall, she said. Her mom explained to her why her older sister — a U.S. citizen who was born in California — was able to do things she wasn’t.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Blanco was born in the Mexican state of Michoacán before coming to the U.S. with her family at age 2. Now, a criminal justice student at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Blanco said receiving Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status five years ago was life-changing.

As a DACA recipient, Blanco was able to get a job as a pharmacy technician, an essential role amid the pandemic, she said. She got her driver’s license and started college.

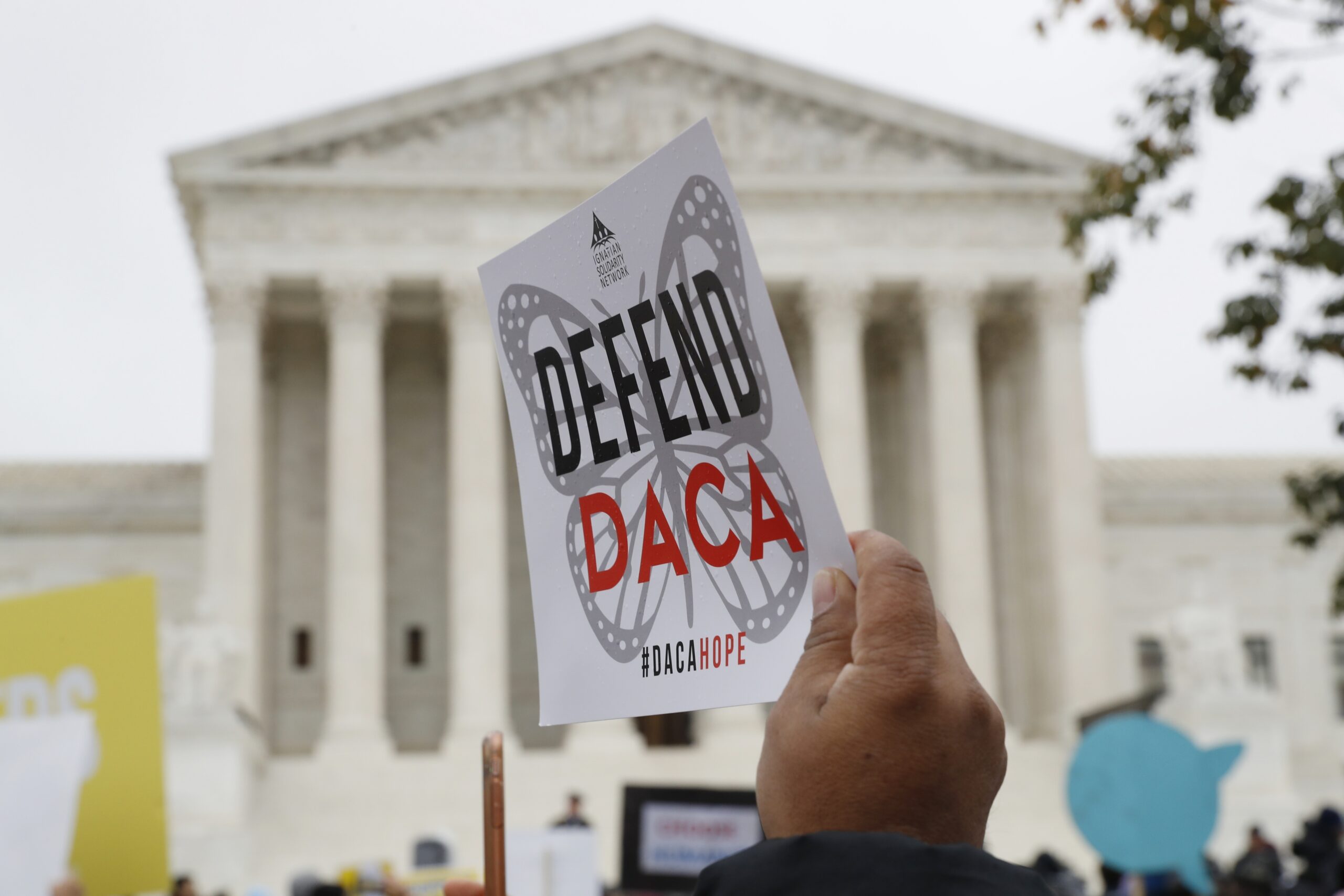

The coronavirus has made this an uncertain time for people across the nation, but it’s especially so for DACA recipients, as the Supreme Court prepares to rule on the Trump administration’s efforts to end the program. A decision is expected as early as this week.

Blanco is one of an estimated 6,600 DACA recipients in Wisconsin, according to immigrant rights organization Voces de la Frontera. More than a third are in Milwaukee.

DACA recipients — there are nearly 700,000 across the country — are protected from deportation. To qualify, individuals must have entered the country as minors. They’re required to pay a fee and renew their status every two years.

In 2017, the lower courts blocked the Trump administration from discontinuing the DACA program, which was created under former President Obama. They said the Department of Homeland Security didn’t adequately explain its reasons for ending the program, a step that’s required by law.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court could uphold the lower courts’ rulings, overturn them and end the program at least temporarily, or declare the program illegal and end it for good.

If the high court sides with the Trump administration, it’s unclear exactly how the program will be wound down. According to Politico, it’s unlikely deportations will occur immediately. Rather, there’s speculation that the administration will use the program as a bargaining chip in negotiations for a bigger immigration deal before the November election.

If Blanco’s future in the U.S. is put in jeopardy, she won’t be the only one affected she said Thursday at a news conference organized by Voces.

Blanco interns at the Farmworker Project, run by Legal Action of Wisconsin, where she helps migrant workers understand their rights, she said. She also helps people from low-income communities fill out legal paperwork at the courthouse.

“Having DACA taken away is not just a disadvantage to me, but it’s an injustice to the people I know I can help,” she said.

Like Blanco, Daniel Gutierrez Ayala is a DACA recipient from Mexico who lives in Milwaukee. His family brought him to the U.S. as a child in hopes of giving him a better life, he said. This a scary time, he said, but he’s still hopeful for his future.

DACA not only allows Gutierrez Ayala to live without fear of being deported, but it also makes it possible for him to go to college, he said. He’s going to be a senior this fall at Cardinal Stritch University with plans to attend law school.

He joined Wednesday’s virtual news conference from his office, where he works for a local immigration attorney helping other immigrants understand the system.

“Without (DACA), honestly I don’t know what I would be doing,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.