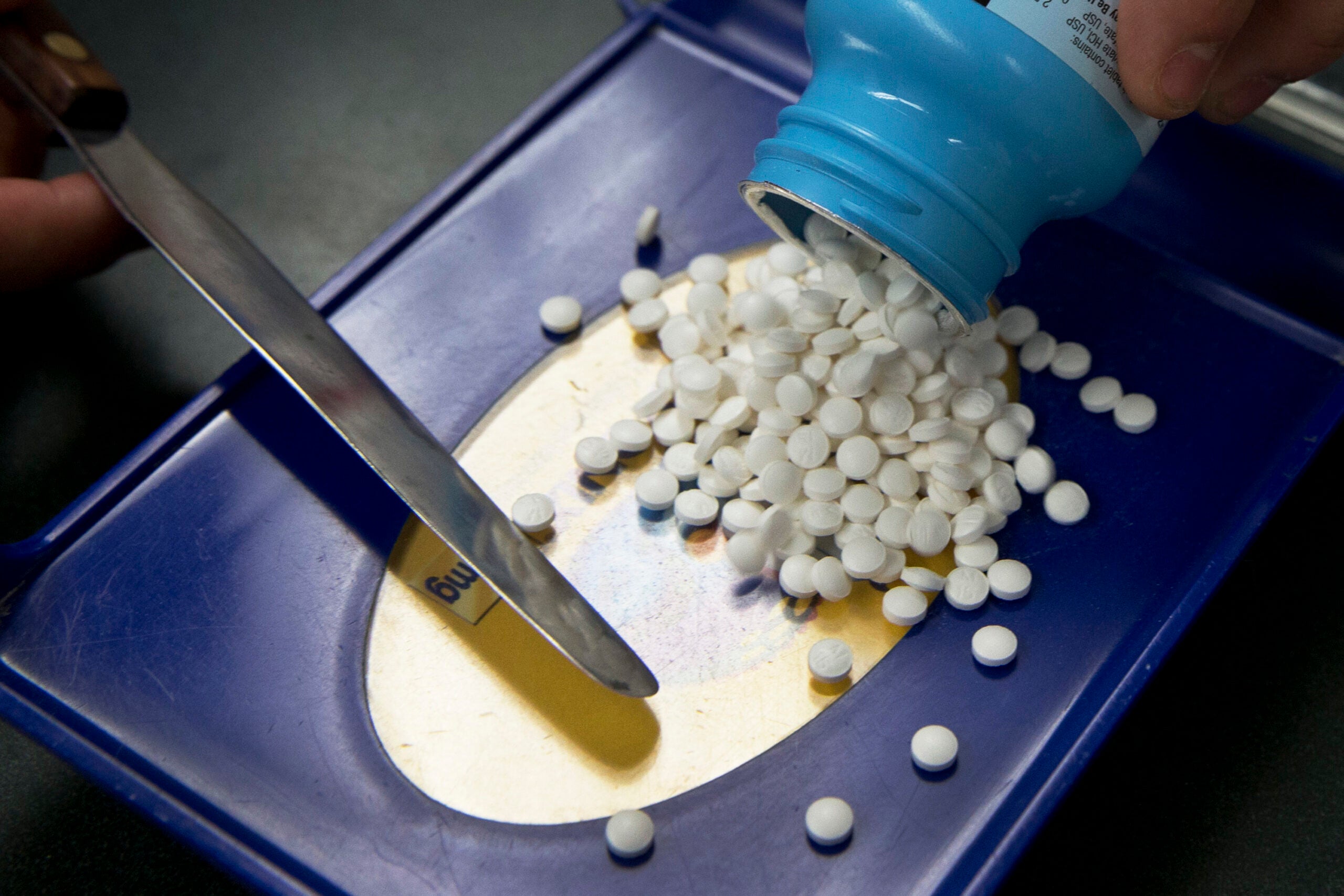

Wisconsin doctors continue to prescribe fewer opioids. From 2015 to 2018, there was a 29 percent drop in prescription painkillers like oxycontin, according to a recent state report.

But opioid deaths have been rising. In 2017, state health officials say there were 916 overdose deaths.

“We expected a decrease in mortality as a result. That is not what we have seen,” said Gina Bryan, an associate professor in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Nursing who worked with the Governor’s Task Force on Opioid Abuse.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The decrease in prescribing comes after controlled substance prescribing guidelines were issued by the Wisconsin Medical Examining Board in January, and after doctors were required to check a state database tracking prescriptions — a change that went into effect in March 2017.

Getting doctors and others to use the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program was initially difficult because health care professionals said it was time consuming and difficult to use.

But a recent survey showed 77 percent of users are now satisfied with how the database works, according to the report.

The most significant decline in opioid prescribing — 14 percent — occurred in 2017, just slightly higher than the 2018 decrease of 12 percent.

In a recent tweet, Rep. John Nygren, R-Marinette, noted the state’s progress in this area. Nygren has been instrumental in passing 30 opioid laws related to misuse and treatment which are part of the state’s HOPE agenda.

According to the most recent report released by the prescription drug monitoring program, there has been a 29% decrease in opioid dispensing from 2015 to 2018, a difference of over 1,448,000 prescriptions. WI has passed 30 bills as a part of the #HOPEAgenda #BudgetFacts #wiright pic.twitter.com/BOShXvVjnr

— John Nygren (@rep89) February 6, 2019

But with less access to prescription painkillers, those who have a history of addiction are turning to heroin and other drugs that may be laced with the synthetic opioid fentanyl. Because it’s so potent, people are more likely to overdose.

“So, we’re seeing heroin with fentanyl in it. We’re seeing cocaine that has fentanyl in it. It’s been adulterated in some way,” Bryan said.

Another factor, she said, is the age of users is going down.

“Younger people are using and they’re not as knowledgeable about what they’re using. They’re not sure what they’re getting,” she said.

With overdose numbers rising, the state is continuing to focus on ways to get people off of drugs. In late December, the Commission on Substance Abuse Treatment Delivery delivered its final report to the Governor’s Task Force on Opioid Abuse.

The report calls for a “hub and spoke” model of treatment where there are locations for both high-intensity care and also treatment provided in the community.

But getting access to treatment and paying for it are often hurdles, especially in rural Wisconsin where people may have to drive long distances.

“Most of our state does not have reasonable access to opioid treatment facilities,” Bryan said. “And so I think when you’re looking a predominantly rural state like Wisconsin you have to look at the ability to get to that (treatment) site.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.