We are now two minutes to midnight.

The Doomsday Clock, the historical (some might say hysterical) tracker of how close we are to a human-made catastrophe, has just advanced by 30 seconds. According to the clock, the last time we were this close to the end of time was in 1953, at the peak of the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union were actively testing hydrogen bombs.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The clock is a metaphor for the anxiety of our time. But it’s also strangely hopeful. It represents a pained yearning that things might improve from this moment, and if they do, the minute hand could be turned back. Angst of the 1950s focused entirely on nuclear disaster. Today, the clock tracks a whole constellation of potential doom for humanity, including climate change, cyberattack and bioterrorism.

Who Created This Clock And Who Is The Keeper Of Its Time?

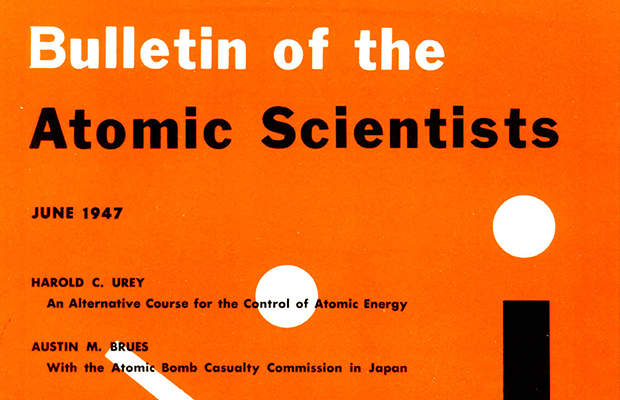

The Doomsday Clock was conceived in 1947 by a group of University of Chicago physicists who worked on atomic weapons as part of the Manhattan Project. Seeking a public call to action on behalf of the scientific community, they published the first edition of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a journal about the potential destruction nuclear weapons could cause.

The original issue featured articles like “A Japanese Scientist Describes Destruction of Cylcotrons,” and “How the American People Feel About the Atomic Bomb.”

Martyl Langsdorf, an artist and wife of the nuclear physicist Alexander Langsdorf Jr, was asked to design a clock for the first cover of the Bulletin.

“I visualized the cover by drawing a clock in white paint on the black binding of (a bound copy of Beethoven’s Sonatas),” wrote Langsdorf, who became known as the “Clock Lady” before she passed away in 2013.

“It was a rather realistic clock but it was the idea of using a clock to signify urgency.”

The first cover was bright orange “to catch the eye,” as Langsdorf. The same design was used for decades.

Original 1947 cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Twice a year now, the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin meet in to Chicago to debate the state of the world, and decide the time. Do they keep the clock at the same time, turn it back, or move it forward?

In January 2018, the decision was made to move the clock forward to two minutes to midnight. The list of doomsday timekeepers reads like a “who’s who” of expertise in nuclear energy and climate change, including 15 Nobel laureates. The original board included Albert Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer.

“They wanted to warn the world,” said Richard Somerville, a climate scientist who specializes in the role of atmosphere and clouds. “They knew better than anyone else.”

Somerville has been on the board for five years, and was part of the group who voted in 2018 to move the clock forward.

“We want to impress the world with the seriousness of the issue,” he said. “We’re not some happy-go-lucky group of people who meet for beers.”

In 2007, Somerville’s research as part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, was honored with a Nobel Peace Prize, alongside former Vice President Al Gore. While Somerville recognizes that some countries — and even some states in the U.S. — have made environmental progress, he says leadership under President Donald Trump is moving both the U.S. and the world backwards.

“(Trump) is dismissing something as real as gravity,” he said. “These are flat-earth people.”

Over the years, the Doomsday Clock pendulum has swung back and forth. In 1963, it was moved back to 12 minutes to midnight, as the U.S. and Soviet Union signed the Test Ban Treaty of 1963. The end of the Cold War moved the clock back even further, adjusting it to 17 minutes to midnight in 1991. But by 2007, the clock had moved ahead to seven minutes to midnight, as polar ice melt, drought and extreme weather accompanied renewed nuclear fears.

As existentially gloomy as the Doomsday Clock is, it has become an American pop culture phenomenon, inspiring songs such as Midnight Oil’s 1984 song “Minutes to Midnight,” and the 1997 Smashing Pumpkins’ “Doomsday Clock.” The band Linkin Park named their 2007 album “Minutes to Midnight,” in reference to the clock.

Followers of the clock are not only those who remember worrying about the Cold War. About half of the visitors to the Bulletin’s website are under the age of 35, according to Janice Sinclaire at the Bulletin.

Somerville says he tries not to obsess about the clock, but he wishes there were more ways to wake people up to climate change, which he says the Pentagon calls a “threat multiplier.”

Whether that’s a chunk of Antarctica breaking off into the sea or a charismatic leader talking about climate change, Somerville thinks it’s going to take building bridges between groups to preserve the environment for future generations.

“Things do change,” Somerville said, pointing to the advances in civil rights he’s seen in during his lifetime. “(But) what we don’t have is a lot of time.”