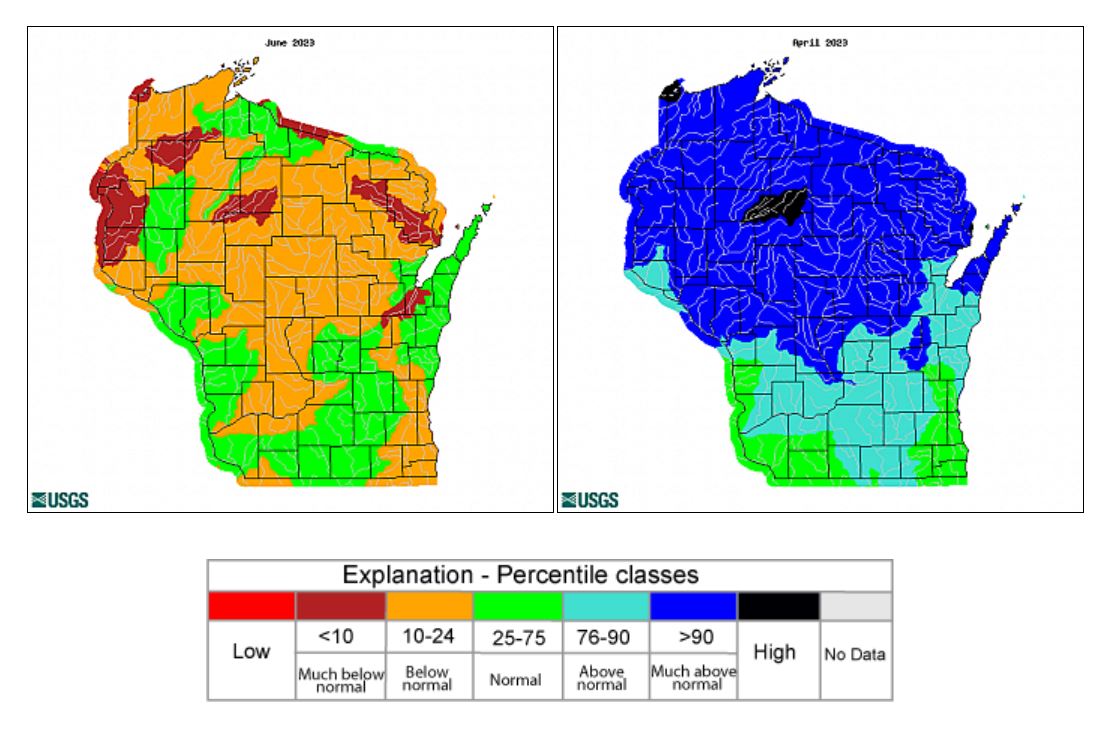

Streams across most of Wisconsin were flowing at above normal rates this spring, but now they’re seeing below normal flows across much of the state as drought conditions continue.

The latest data from the U.S. Drought Monitor shows nearly 93 percent of the state is under drought conditions, affecting 5.5 million residents. Around 65 percent of Wisconsin is experiencing moderate drought, and almost 25 percent of the state is now under severe drought conditions. As of June, the state had seen a shortfall of anywhere from 2 to 6 inches of rain and warmer than normal temperatures.

Rob Waschbusch, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, said Wisconsin had seen high flows due a wet spring. Since May, he said conditions have dried up and flows are declining.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“We’re low right now,” Waschbusch said. “We’re not extremely low, but we could sure use some rain.”

Mike Fienen, a USGS research hydrologist, said the shift in flows is interesting because recent years have been wetter. In fact, the last decade included some of the wettest years on record.

“We’re seeing drops in quite a few rivers, but a lot of them are still above their long-term average because of the wet conditions we’ve experienced for a while,” Fienen said. “But, a pretty precipitous drop off in the last couple of months.”

In central Wisconsin, flows on one river that’s been known to dry up in stretches due to dry spells and groundwater pumping are currently running below the minimum healthy level set by the state.

George Kraft is a professor emeritus of water resources at UW-Stevens Point. He said the Little Plover River, a class 1 trout stream in the state’s Central Sands region, has been running at about three-fourths of the public rights flow established by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources for one spot on the river at County Road R. The minimum flows set by the state are intended to protect fish and wildlife habitat.

Kraft said the river should be running at 4 cubic feet per second on that section of the river, but it was flowing at 3.2 cubic feet per second during the first week of July.

“The Little Plover should be chugging along very healthily today if we weren’t pumping all the water surrounding it right now,” Kraft said. “It’s bad enough that it’s below healthy flow if you care about things like trout and critters, but we could be facing a dry up this year.”

It’s not uncommon for flows to fall below the minimum levels set by the DNR. The Little Plover River runs for about 6 miles before joining the Wisconsin River south of Stevens Point. It has dried up in stretches from 2005 to 2009 due to limited rain and groundwater pumping in the region, causing fish kills.

A 2016 study found the river is a groundwater-fed stream that makes it vulnerable to impacts from nearby pumping. The findings revealed irrigation accounts for 80 percent of all water used in the river basin each year.

The Central Sands area has more than 3,000 high capacity wells that withdraw as much as 100,000 gallons of water per day. The area is the state’s largest production area for potato growers. Tamas Houlihan, executive director of the Wisconsin Potato and Vegetable Growers Association, recently told Wisconsin Public Radio that more than 95 percent of the state’s crop is irrigated.

“Certainly during times of drought, when the growers really need to pump water, that can exacerbate dry conditions for lakes and streams,” Houlihan said in June. “But, we do put the water right back down from where we’re pumping it, and so there’s significant recharge every time they pump water. So, I don’t think quantity (of pumping) is the big issue anymore.”

Hydrologists say not all the water pumped from the ground for irrigation returns to groundwater because some of it is used by plants.

In recent years, the group, along with other public and private partners, has worked to take land out of production and decommission a high capacity well to help increase flows on the Little Plover River. But, Kraft contends such projects haven’t yielded much results.

“If we want a viable stream here, we have to ratchet back pumping,” Kraft said.

Fienen with the U.S. Geological Survey added that not all streams have a public rights flow to determine minimum healthy levels, noting the health of a stream is dependent on many factors that vary by location.

In northeastern Wisconsin, the Peshtigo River is running so low right now that one rafting outfit is not running trips down the river. Nick Guarniere, owner of Kosir’s Whitewater Rafting in Silver Cliff, said the river is the lowest his family has seen for this time of year in 20 to 30 years.

“The first mile, mile-and-a-half right now is so low that it’s just straight rock,” Guarniere said. “You look down it, and there’s pretty much no way to get down at the moment.”

Guarniere said thousands of people come to raft the Peshtigo River each summer. They’re currently offering to take people rafting down the Menominee River instead, but they’ve had to turn some people away. The rafting outfit still runs tubing trips on the lower section of the Peshtigo River, which he said is the only thing saving their summer.

“We’re praying for rain at the moment,” Guarniere said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.