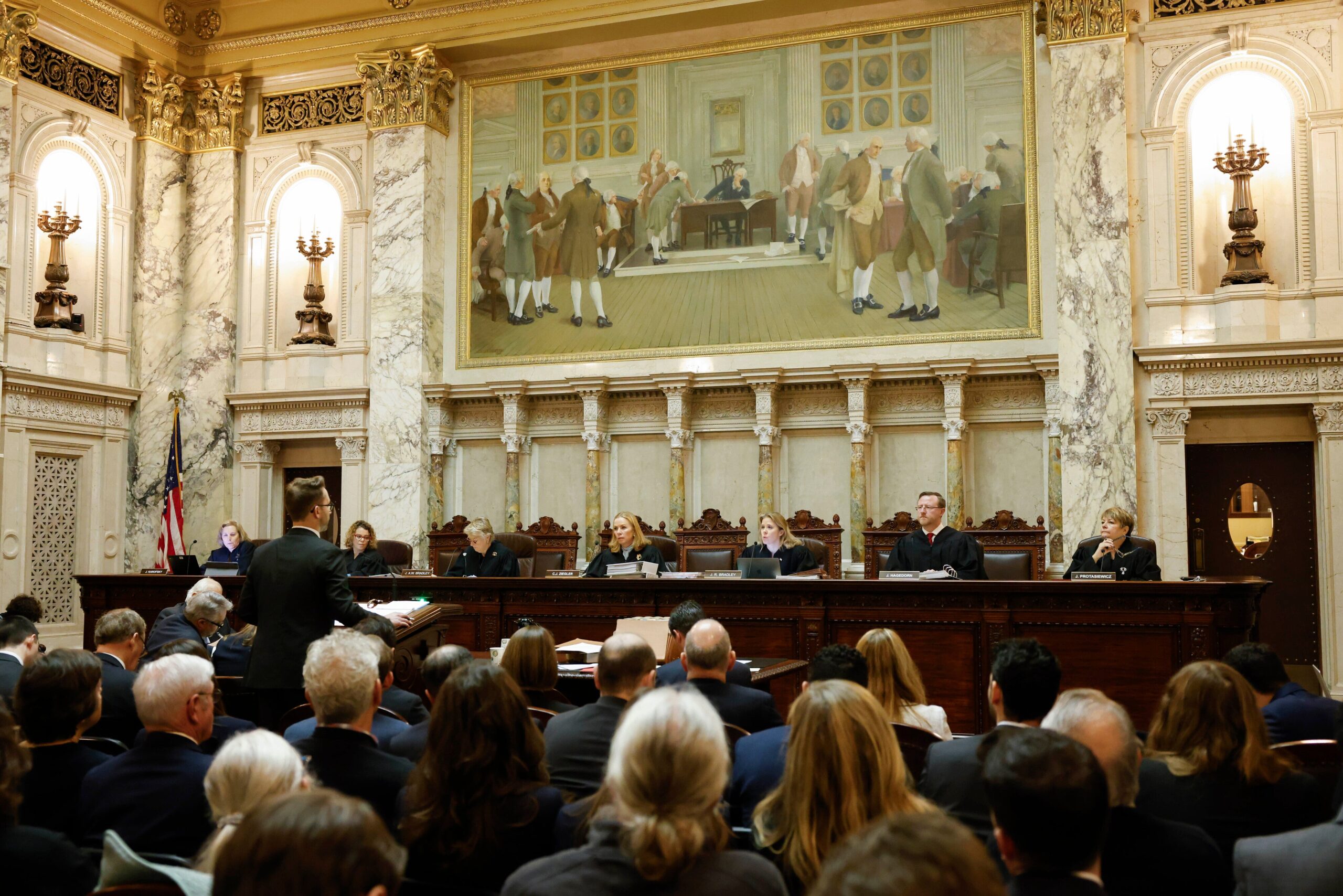

Liberal members of the state Supreme Court asked attorneys how the court could redraw the state’s political maps during oral arguments in Wisconsin’s closely-watched redistricting case Tuesday, with some suggesting that justices should have broad leeway if they find the current Republican-drawn maps unconstitutional.

Over the course of nearly three hours, justices heard from attorneys representing Democrats hoping to see current voting districts declared unconstitutional and attorneys representing Republicans who want to see the case dismissed. Both sides faced pointed questions from conservative and liberal justices alike.

While the case at its core is about political power and democracy, much of the discussion centered around two narrow legal questions. The lawsuit claims the current maps violate the Wisconsin Constitution’s contiguity requirements for voting districts. It also argues the court’s previous conservative majority violated the state Constitution’s separation of powers clause when it approved maps that were identical to the ones Gov. Tony Evers had vetoed.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But conservative justices questioned the timing of the case and whether it should be before the court at all. The redistricting lawsuit, filed by 19 Democratic voters from Wisconsin, was submitted one day after the investiture of liberal Supreme Court Justice Janet Protasiewicz, which gave liberals their first majority in 15 years.

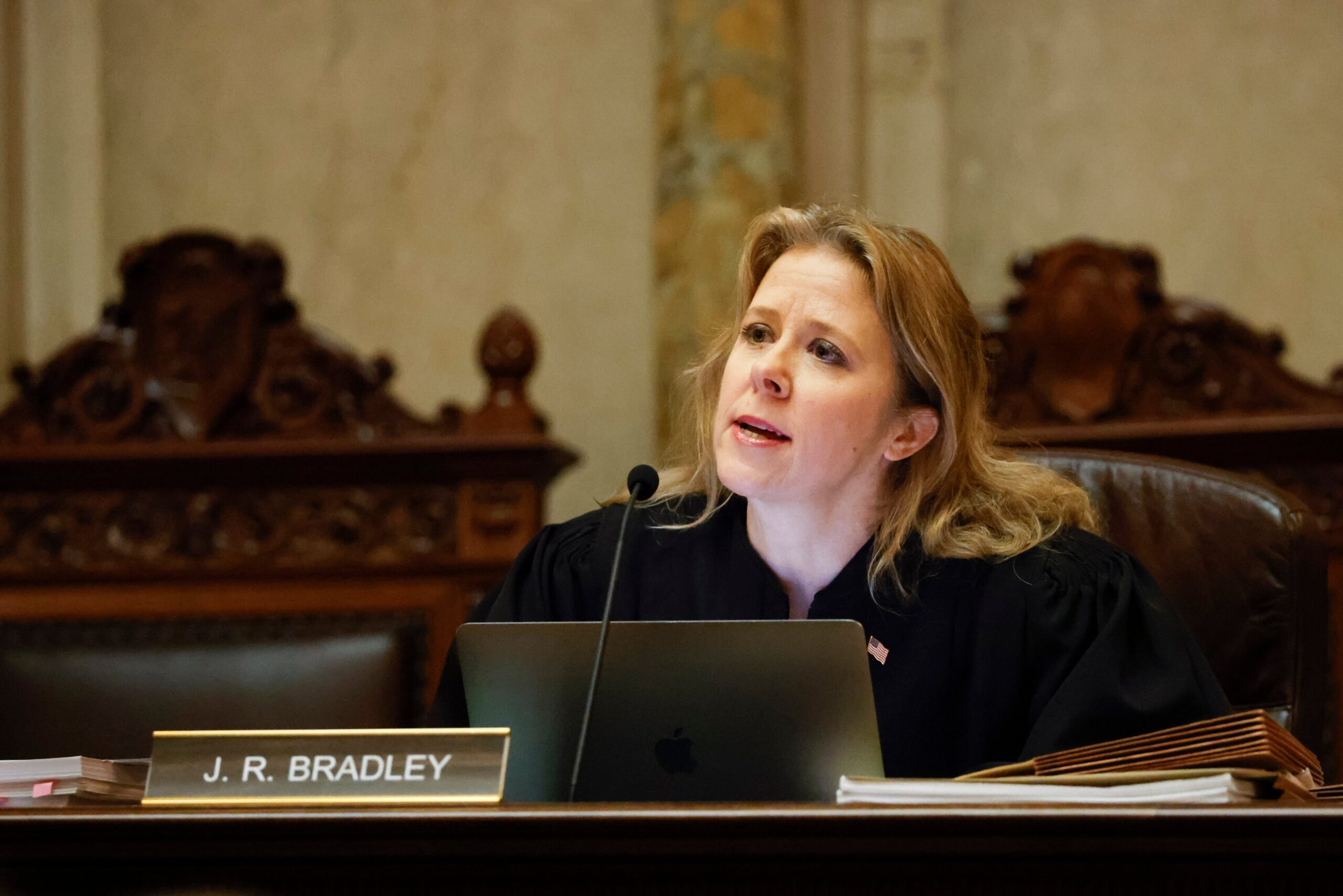

Moments after attorney Mark Gaber, who is representing Democrats, began his opening remarks, conservative Justice Rebecca Bradley interrupted, noting that the court had already dealt with redistricting after the last U.S. Census.

“Where were your clients two years ago?” Bradley asked. “Everybody knows that the reason we’re here is because there was a change in the membership of the court,” she later added.

Bradley argued that if Democrats had an issue with the contiguity of the maps, they could have raised it the last time redistricting was challenged, arguing that it had been settled law since the early 1970s.

Gaber said his clients couldn’t have known what their legal claims were when the 2021 redistricting suit was filed because the court didn’t choose a final map until the last minute. He also challenged the idea that a new lawsuit was off-limits.

“I’m unaware of any authority that would say that if you don’t raise a constitutional claim in 12 days, that you’re forever precluded from raising that claim in the future,” Gaber said.

Talk of contiguity dominates discussion during arguments

Wisconsin’s Constitution states that when Assembly voting districts are drawn, they should be “bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.” Senate districts, according to the Constitution, should not split Assembly districts, and should also be made of “convenient contiguous territory.”

During Tuesday’s arguments, attorneys for Democrats and Republicans argued with justices about the literal definition of the word contiguous, including how the state’s framers defined it in 1848 and how state lawmakers modified that definition more than 50 years ago.

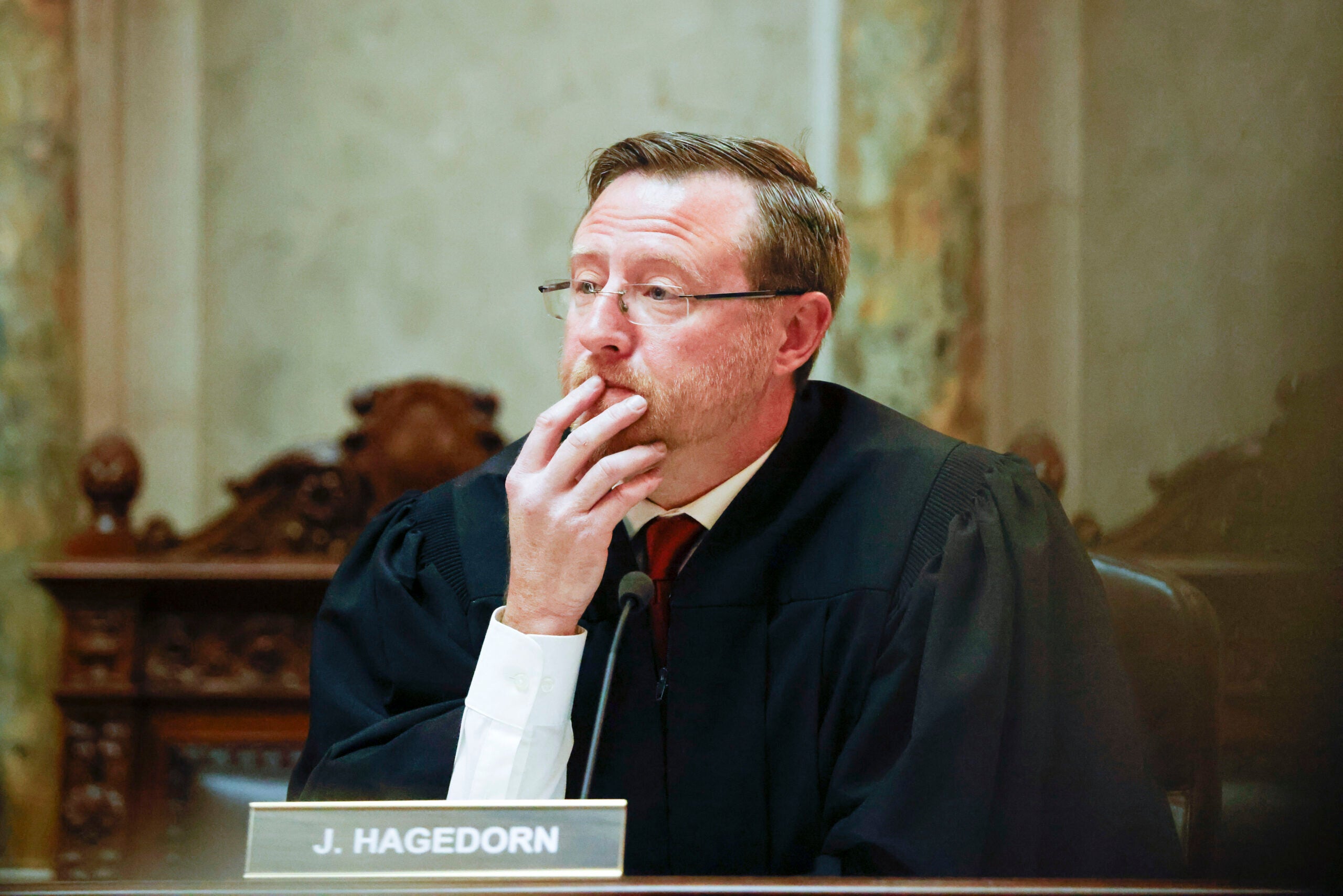

Conservative Justice Brian Hagedorn noted the contiguity issue evolved when state lawmakers allowed towns and municipalities to annex land from neighboring towns. Hagedorn said the claim by Democrats that contiguity means voting boundaries must physically connect could contradict the Constitution’s requirement that voting wards not be split.

When the court took up redistricting two years ago, Hagedorn said all of the maps submitted by parties took a similar approach to deal with the contiguity question.

“A sensible resolution to this problem is to keep these municipally annexed lands together and that best complies with potentially incompatible constitutional commands,” Hagedorn said.

Gaber disagreed.

“There’s not a single place in Wisconsin where it’s not possible to bound the districts by county, town and ward lines and to have the district be 100 percent contiguous,” Gaber said.

Separation of powers claim argues court got it wrong in last redistricting decision

Assistant Wisconsin Attorney General Anthony Russomanno, representing Gov. Evers, focused much of his arguments on the separation of powers issue. He argued conservative justices “put a thumb on the scale” in favor of Republicans who control the Legislature during the last redistricting lawsuit.

In 2021, the court told parties to submit “least changes” maps, that were similar to maps passed by Republicans and signed by former Republican Gov. Scott Walker in 2011. Rather than draw new maps for the court, Republicans submitted the same ones they had earlier passed, the same ones Evers had vetoed.

“Don’t adopt the map that failed the political process,” said attorney Tamara Packard, who is representing Democratic state senators. “It’s that simple.”

Justice Bradley again asked why the governor didn’t raise the separation of powers argument after the last round of redistricting. Russamanno said that wasn’t the focus of the previous litigation.

Justices skeptical about ordering new elections for all 132 lawmakers

In addition to tossing GOP maps and drawing new ones, the Democratic redistricting suit is asking the court to hold new elections for all 132 state lawmakers. That includes state senators who were elected in 2022 and have two more years left on their existing terms. On this issue, there was at least some agreement between the court’s ideological camps.

“I can’t imagine something less democratic than unseating most of the legislature that was duly elected last year,” said Justice Bradley, the court’s most outspoken conservative.

“I have to say that I agree it’s an extreme remedy,” said Justice Protasiewicz, the court’s newest liberal.

Protasiewicz then asked attorney Tamara Packard, who is representing Democratic state senators, if there are examples of other courts doing it before.

“I don’t know of any,” Packard said. “But this is a really big problem.”

Attorney Taylor Meehan, who is representing Republican lawmakers, said the best argument against cutting lawmakers’ terms short is the court’s decision in December 2020 to reject a lawsuit from former President Donald Trump seeking to overturn his loss to President Joe Biden.

“I cannot see how you refuse to recount or unwind lawfully-counted ballots in a case involving the Republican presidential candidate, but you would do so here for lawfully-elected senators,” Meehan said.

Liberal justices ask for advice on drawing new maps

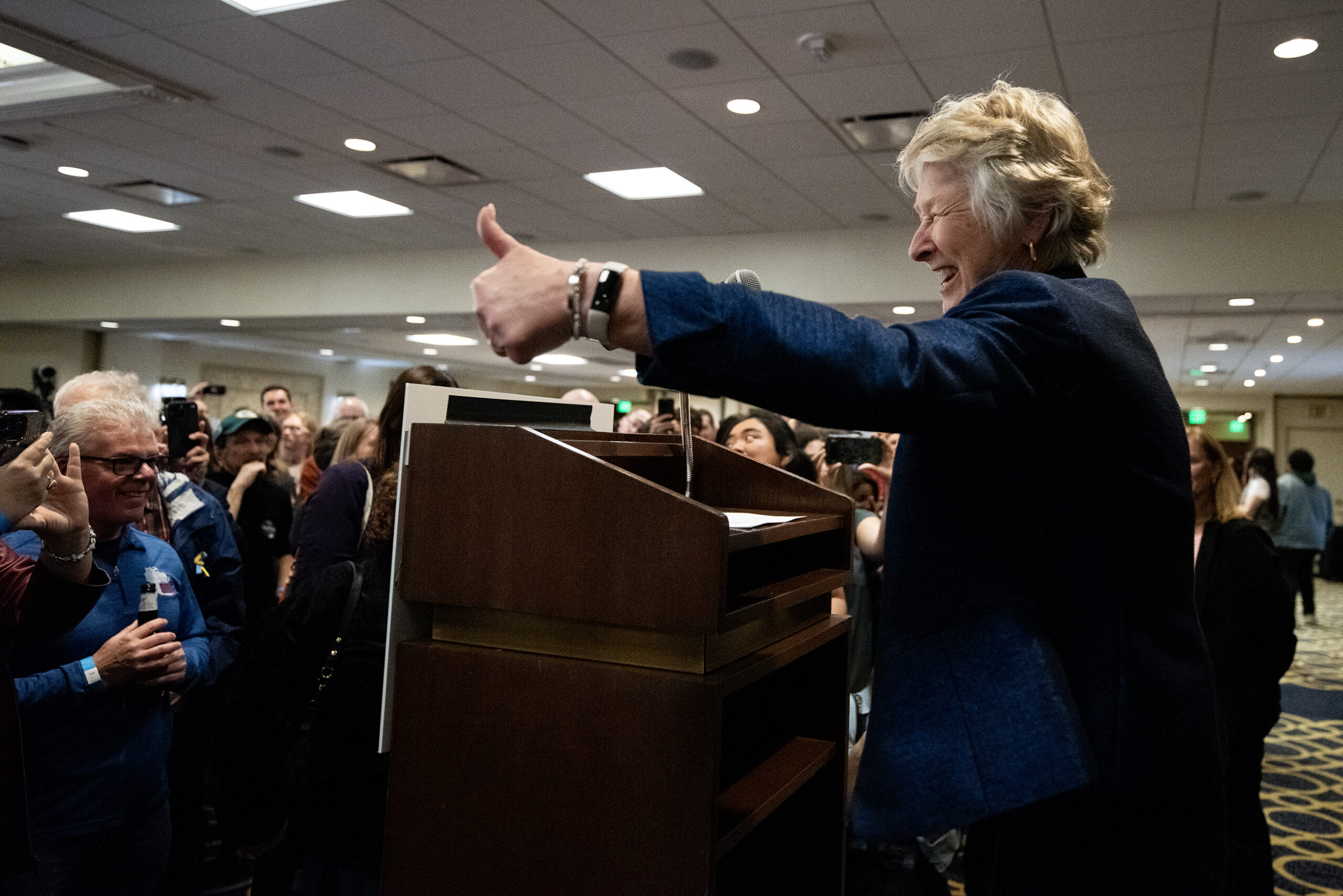

While the case focuses on other legal questions, justices alluded to the idea that the maps represent a partisan gerrymander, one that gives Republicans undue legislative power in a state known for close statewide elections. The court’s new majority declined to decide that question directly, but liberal Justice Jill Karofksy called it “the big white elephant in the room.”

“I do wonder if this court gets to the place where we either need to adopt maps based on the parties presenting them to us or we get to the place where we are going to be drafting our own maps,” Karofsky said.

Karofsky asked parties whether justices need to consider partisan fairness when drawing new maps. Russamanno, the attorney for Evers, said the court should.

Liberal justices asked attorneys from both sides for suggestions about who they would recommend to draw new maps. They also discussed the idea of having various parties in the case send proposed maps to the court, with justices deciding which was the least politically skewed.

Meehan told the court she didn’t want to assume justices are “jumping straight to a remedy without giving the Legislature an opportunity” to weigh in. Meehan said the court could address contiguity issues with minimal changes.

Attorney Sam Hirsch, representing a group of mathematicians intervening in the case, said the key question justices should consider is “which maps are most likely to support rather than thwart majority rule” in Wisconsin.

Hagedorn asked Hirsch what it means to “thwart” majority rule.

“How many Republicans are permissible?” Hagedorn said. “How many Democrats?”

Hirsch answered that in years where Republican candidates get more votes than Democratic candidates across the state, “they should control the legislature and vice versa.”

“It’s that simple,” Hirsch said. “It’s called majority rule, and I hope the court stands up for it.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.