Wisconsin has seen an uptick in union activity in recent years, and labor leaders hope to carry that momentum through 2024 and beyond.

There have been 16 strikes and 30 labor protests in the state since the start of 2021, according to data from Cornell University’s Labor Action Tracker. That data includes a slew of strikes that happened across the state last year.

Case tractor factory workers in Racine started 2023 on strike. In July, Leinenkugel’s Brewery workers in Chippewa Falls went on strike for the first time since the 1980s. In August, unionized service workers at ThedaCare in the Fox Valley gathered to demand better pay and in November, United Auto Workers locals in Wisconsin joined in that union’s national strike.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The state also saw efforts by workers to form new unions in Wisconsin. That includes beer vendors at Lambeau Field organizing, Planned Parenthood workers starting efforts to unionize, journalists at Wisconsin Watch forming a union and video game testers in Milwaukee unionizing. Workers at Colectivo Coffee in Madison and Milwaukee ratified their first union contract with the company after organizing efforts began in 2020. In June, Starbucks workers in Madison voted overwhelmingly to form a union, becoming the state’s sixth unionized Starbucks and the second in the city.

This surge in union activity comes as labor markets in Wisconsin and nationally remain tight, which experts say gives workers more leverage to negotiate for better wages and benefits. And public opinion data shows unions today are viewed more favorably than they were a decade ago.

Wisconsin AFL-CIO president Stephanie Bloomingdale said union activity in the state last year often translated to wins for workers.

“We are seeing working people continue to come together to organize new workplaces in Wisconsin and also to participate in workplace actions when it comes to contract negotiations,” she said. “Whether that be through strikes (or) powerful collective bargaining, we’re seeing wins at the bargaining table that workers see in their paychecks every day.”

Union membership in Wisconsin rebounded slightly last year after falling to its lowest level on record in 2022. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the number of union members in the state increased from 187,000 in 2022 to 204,000 last year.

At the same time, labor unions were overwhelmingly popular nationally in 2023, with 67 percent approval as of August, according to polling from Gallup.

“The appetite is out there, the need is out there (and) people see the need to take more control over their situation at work and to increase their wages and benefits,” said John Drew, former president of the United Auto Workers Local 72 in Kenosha. “Unions have to continue to devote resources to organizing.”

Drew also said widely publicized national strikes in 2023 — from those held by writers and actors to UAW strikes marking the first time a sitting U.S. president joined a picket line — could serve as a turning point for the labor movement going forward.

“In 2023, unions really stood up and fought for higher wages, better working conditions (and) better benefits,” he said. “I do think those high-profile battles do focus people’s attention and encourage people to want to unionize.”

Where did labor momentum come from?

While 2023 may have felt like a big moment for the labor movement, there was momentum leading up to it in the preceding years, said Saba Waheed, research director of the Labor Center at UCLA.

Public approval for unions nationally bottomed out in 2009 at about 48 percent of Americans but began to tick up through the early part of the 2010s and at a faster rate since 2016, according to Gallup.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic happened, completely restructuring employees’ relationships to workplaces, Waheed said.

“There were often these profits on the company side, but then all this risk on the frontline workers’ side,” she said. “We saw some massive shifts in the way that we were thinking about work, and especially (for) the workers that sustain a lot of our cities and neighborhoods.”

As pandemic precautions eased and the economy began to ramp up again after slowing to a crawl, the labor market tightened, shifting power to workers, Waheed said.

The unemployment rate in Wisconsin has been below 4 percent since mid-2021, and the state’s labor force participation rate has consistently been better than the national rate. The state had 2.4 jobs for every one jobseeker as of last October.

“Most employers — whether it’s retail, fast food, manufacturing, you name it — they’re all feeling the effects of the labor shortage,” said Mark Westphal, president of the Fox Valley Area Labor Council. “For the first time in many years, workers actually have had conditions more in their favor. Employers can’t afford strikes (or) work stoppages.”

Public sector workers face uphill battle

Despite momentum behind unions in recent years, membership has been trending downward in Wisconsin for decades. In 2000, 17.8 percent of Wisconsin workers were in a union. That number was down to 7.4 percent in 2023.

Laura Dresser, associate director of the left-leaning COWS economic think tank at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said state policies like Act 10 and Wisconsin’s “right to work” law have played a major role in the decline.

Act 10, signed into law by Republican former Gov. Scott Walker in 2011, effectively stripped most public-sector unions of collective bargaining rights, which allowed unions to negotiate with employers on everything from pay and benefits to safety policies. The right to work law, signed by Walker in 2015, prevents private sector unions from requiring workers covered under a collective bargaining agreement to pay union dues.

“Those are two pieces of state policy that pushed hard against workers’ ability to maintain or organize unions,” Dresser said. “It’s just a lot harder to get more people in unions in Wisconsin than it was 10 years ago.”

Late last year, seven Wisconsin unions representing teachers and other public workers filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Act 10. The lawsuit argues that the law’s exemption of police, firefighters and other public safety workers from the bargaining restrictions violates the Wisconsin Constitution’s equal protection guarantee. The case is currently in Dane County Circuit Court, but could eventually make its way to the State Supreme Court.

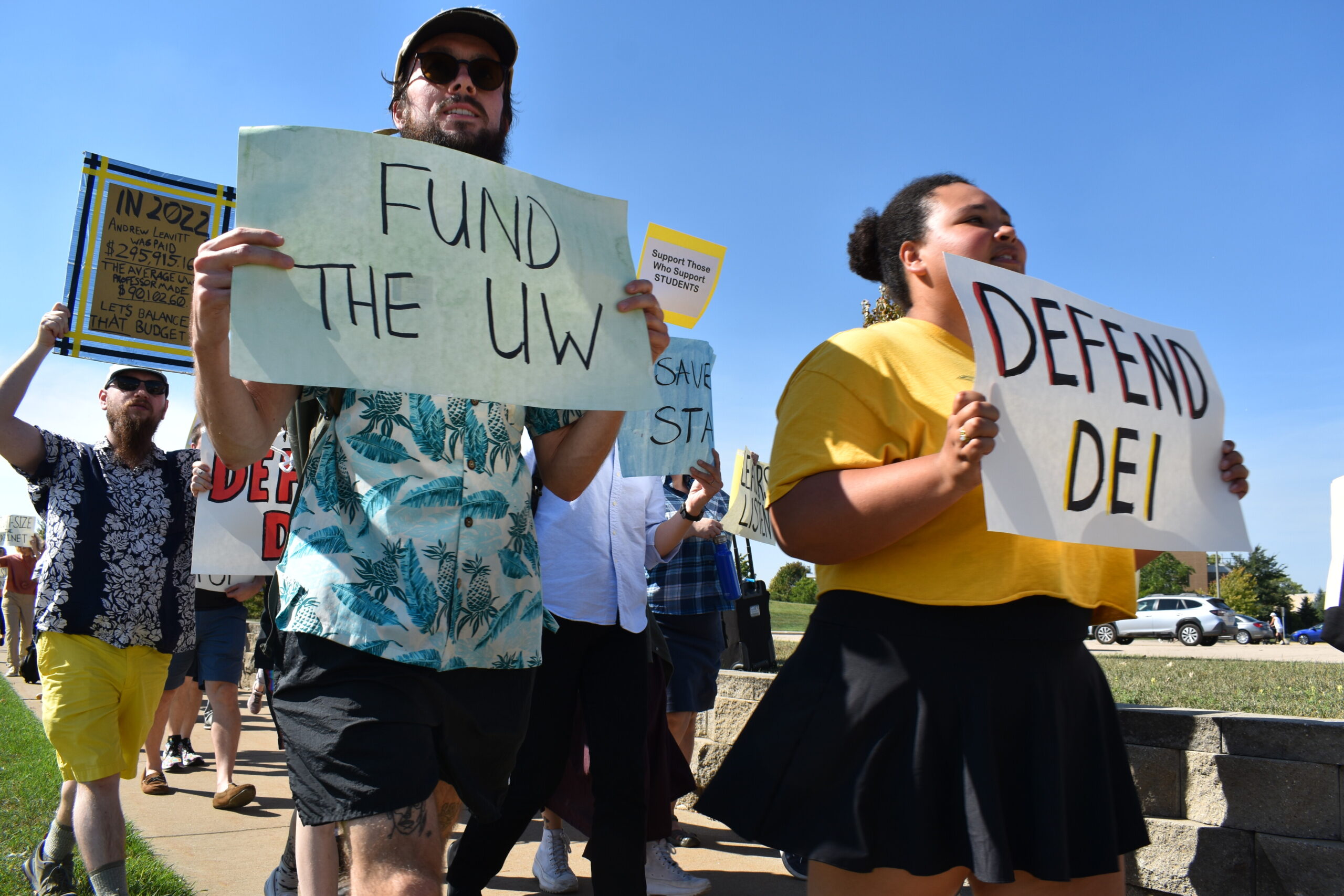

In the meantime, a union at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh has worked to make a difference on campus without collective bargaining.

In October, the United Faculty and Staff of Oshkosh, or UFSO, organized a rally to protest the university’s plan to address its budget deficit through furloughs and shedding roughly 200 positions.

UW-Oshkosh political science professor and UFSO president David Siemers said the union uses its First Amendment rights to try to make a difference in campus decision-making because its hands are tied when it comes to collective bargaining.

UFSO previously held a protest on campus in 2022, at which it successfully prevented the university from outsourcing its custodial staff in a planned cost-cutting move. Siemers said the October gathering helped ensure workers making less than $33,000 annually will be exempt from furloughs.

“The First Amendment is our in — that’s how we can operate in this environment,” Siemers said. “All we want is to be at the table, and to forge the next generation of what the UW System looks like.”

Shift to service economy also plays a role

Beyond state policy decisions, Peter Rickman, president of the Milwaukee Area Service and Hospitality Workers Organization, said a shift away from manufacturing toward a more service-based economy also contributed to the erosion of union density.

In March 2000, Wisconsin had about 600,000 manufacturing jobs, according to the Federal Reserve Bank Of St. Louis. That year, about 456,000 Wisconsin workers were union members. Manufacturing jobs plummeted to roughly 426,200 by March 2010. Union membership also fell to approximately 355,000 that year.

Manufacturing jobs in the state have rebounded gradually since 2010 to roughly 479,200 as of November 2023. But union membership has only continued to decrease. As of 2023, roughly 204,000 workers were union members.

Average monthly leisure and hospitality jobs in the state, meanwhile, have increased from 199,906 in 1990 to 277,425 in 2022, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development.

Historically, most service sector jobs were not unionized. Rickman said the labor movement largely ignored the industry years ago, forcing unions to play catch-up now.

“The service sector has grown in Wisconsin, and grew up at a time when unionism in this state was strong enough that it could leverage that power to build a union-organized service sector but didn’t do so,” Rickman said. “Now we’re confronted with growth of (the) non-union service sector work that is taking on a greater share of employment.”

And while manufacturing jobs are now considered family-sustaining, it wasn’t always that way.

Dresser said factory jobs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were often low-paying and dangerous. She said unions were key to improving those jobs, and could do the same for the often low-paying service industry.

“It doesn’t have to be that your service-sector jobs never provide benefits or have bad schedules that are unpredictable and mean that workers can’t count on being able to pay their rent,” she said. “It is something we tolerate, and workers are (becoming) less willing and able to tolerate it.”

How to boost membership

Although 2023 saw growth in union activity, labor leaders say more needs to be done to build on that momentum.

Some union officials say the lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Act 10 will be key to the future of public sector unions in Wisconsin.

Regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome, labor leaders say organizing in the service industry will also play an important role in returning to Wisconsin’s union roots.

Rickman said the growth of the traditionally non-unionized service sector has led to an erosion of the middle class and an explosion in income inequality. He said he believes unionizing efforts in the service sector could help rebuild the middle class.

“This is something that matters to every single one of us who punches a clock to bring home a paycheck,” Rickman said. “The future of our economy, the future of our communities, the future of our neighborhoods and our families hangs in the balance.”

Jon Shelton, a professor at UW-Green Bay and vice president for Higher Education for the American Federation of Teachers-Wisconsin, said government reforms to capitalize on the push to organize in the service sector would also help. He said that the federal law governing labor relations “makes it really difficult” for workers to form a union and get a contract.

When a petition is filed with the National Labor Relations Board for a union election, Shelton said companies often begin holding meetings with workers to persuade them not to unionize.

Shelton said workers also face obstacles after forming a union, pointing to allegations that Starbucks refused to negotiate with numerous unionized cafes.

“There needs to be significant reform to make it easier for workers to vote for a union and collectively bargain,” he said. “The playing field is not level.”

Despite obstacles ahead, Bloomingdale with the AFL-CIO said unions and workers have a tremendous opportunity coming out of 2023.

“This has been a dynamic year for workers and labor unions in Wisconsin and nationwide,” said Bloomingdale. “We will look back at this and probably think about this as a spark for new organizing … because, generally, workers are really getting fed up with the status quo.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.