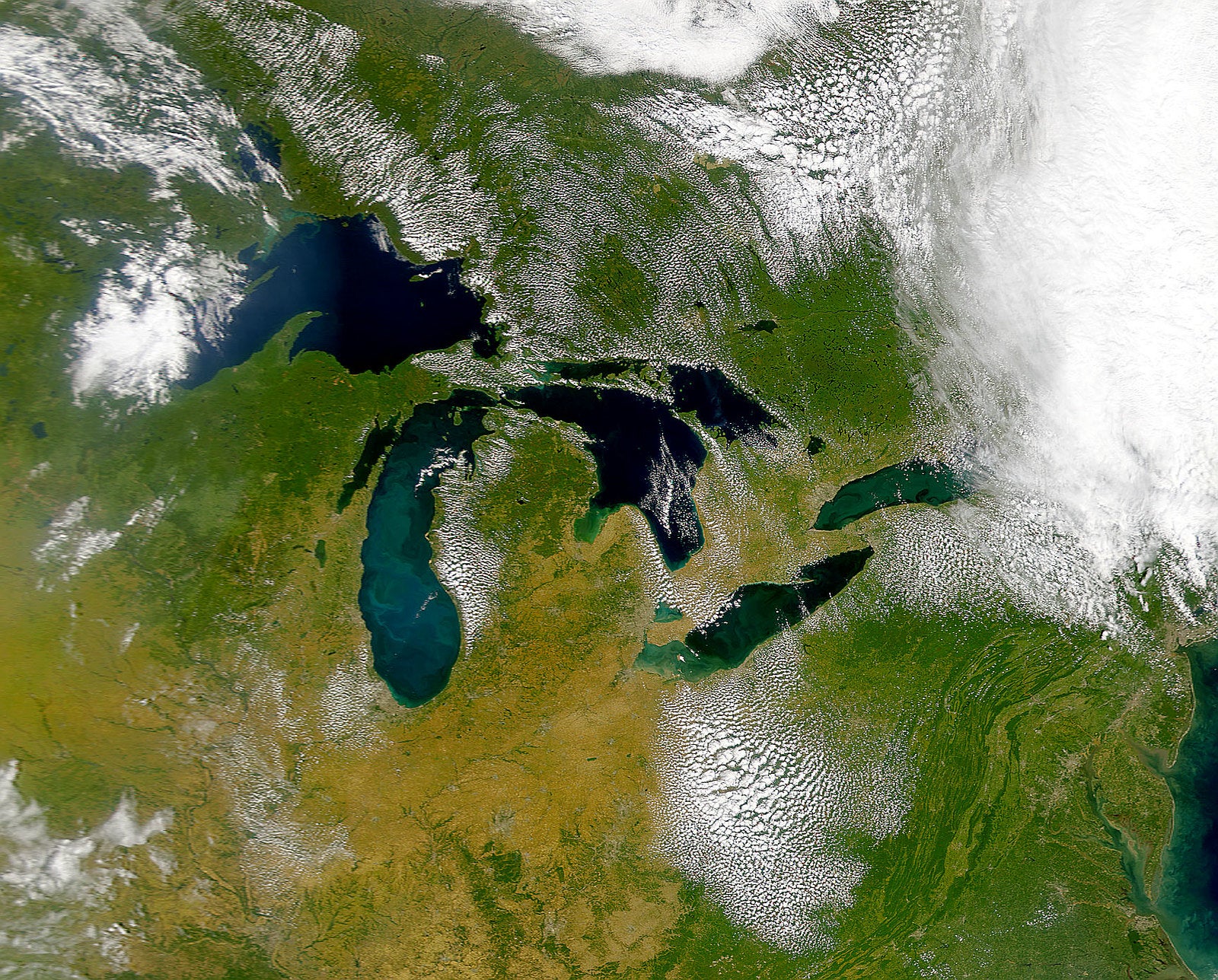

Average ice cover on the Great Lakes dropped to one of the lowest levels on record this winter as the region has witnessed warmer than normal temperatures. Less ice sets the stage for the lakes to warm up sooner earlier in the year, and researchers say that could affect water quality and the food web.

This year has tied with 1998 and 2020 for the third-lowest average ice cover on the Great Lakes since the beginning of the season at 5.7 percent as of Sunday, according to researchers with the NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab.

Average ice cover only dropped below that level when it reached 5.3 percent in 2002 and a record low of 3.8 percent in 2012, according to records dating back 50 years. In that same span, the average annual ice cover on the Great Lakes has been around 25 percent.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

James Kessler, a physical scientist with the lab, said air temperature is a primary factor that determines ice cover on the lakes.

“We’ve had abnormally warm temperatures in both January and February,” Kessler said. “We did have short periods of cold weather, but it was so brief that the lakes didn’t really respond in time. It takes persistent cold air in order for the lakes to cool enough in order to freeze.”

Average air temperatures reached about 7 degrees Fahrenheit above normal in the Great Lakes region this year and 11 degrees above normal across the basin in January.

Ice cover on the Great Lakes only climbed to a high of 22 percent this year, which also placed it among the top ten years for lowest maximum ice cover. This year marks the seventh-lowest since 1973. The long-term annual maximum ice cover averages around 55 percent.

At its highest, ice cover on Lakes Superior and Michigan reached about 20 percent this season. Lake Erie, the shallowest of the lakes, frequently freezes completely. But this year, only 40 percent of the lake froze, at most.

Over time, maximum ice cover on the lakes has dropped at a rate of about 5 percent each decade. As climate change warms lakes around the world, scientists have found ice-covered lakes like Lake Superior are warming more rapidly than those without ice cover. That can have a variety of effects on lake ecology.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota in Duluth have noted less ice can lead to warmer summer water temperatures.

Bob Sterner, director of UMD’s Large Lakes Observatory, said research has shown warmer waters promote the formation of algal blooms in Lake Superior. He said the lake’s characteristics mean average summer water temperatures are strongly related to winter conditions.

“Logically, one could conclude that a low-ice year like we’re experiencing this year is one which is more likely to produce blooms in the summer than a high-ice cold winter would,” Sterner said.

For example, Sterner noted 2012 was the first year that blooms were documented on Lake Superior. That year also marked the second-lowest on record for maximum ice cover on the Great Lakes. He added intense summer rainfall also played an important role in the formation of larger blooms in 2012 and 2018.

There’s also evidence that decreasing ice cover can affect fisheries, according to Ted Ozersky, an associate professor of biological limnology at UMD.

“Loss of ice disrupts the eggs that are laid in late fall and incubate over the winter, and the loss of ice leads to more wave disruption and lower recruitment of some fish species,” Ozersky said.

Research has shown that less ice can lead to lower recruitment of yellow perch in Lake Erie, and studies have also shown that whitefish are negatively impacted by ice loss.

As winters warm and see less ice, Ozersky said researchers are studying whether warmer summer waters could lead to a shift in the kind of zooplankton or tiny shrimp in the water column. He said the kind and abundance of those organisms are important because zooplankton serve as food for fish, and they graze on phytoplankton or tiny plants that affect the formation of algal blooms.

However, he cautioned that scientists know little about winter conditions in the lakes, which affects their ability to understand how that drives changes throughout the year. But there’s been growing interest in recent years to fill that information gap.

In the meantime, communities have witnessed how the loss of lake ice can play a role in more lake-effect snow, according to Hilary Dugan, an assistant professor with UW-Madison’s Limnology Center. She noted lakes lose less water to evaporation when they freeze.

“When storms come across the Great Lakes and water can evaporate, we’re sort of seeding these lake-effect storms that then have tremendous impact on the downstream cities,” Dugan said.

She pointed to a huge lake-effect storm that dropped more than 50 inches of snow on Buffalo, New York for nearly a week in December.

On Lake Superior, Duluth has also seen its 6th snowiest winter on record. Dugan said the loss of lake ice can also leave shorelines unprotected and more at risk of erosion and flooding, especially in years with high lake levels.

Less lake ice can also affect how people interact with the lakes. For example, the ice road failed to form between Madeline Island and Bayfield this year. That means less freedom for island residents to travel back and forth, and less downtime for the ferry line to maintain its vessels. Reduced ice cover can also affect recreation and safety for anglers who ice fish.

But less ice can also benefit Great Lakes shipping. The Ports of Duluth-Superior and Green Bay witnessed an extended shipping season in January with some of the latest cargo shipments in nearly 50 years. Vessels have been able to move more freely at the start of this year’s season compared to last year when ice slowed the movement of ships on the upper lakes.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.