With a record low unemployment rate of 2.8 percent, Wisconsin wants to grow its workforce.

While there are several reasons the state’s available pool of workers has gotten smaller, one of the starker reasons is the growing population of people in the state with a criminal record. That criminal record often means employers will not hire a potential worker — creating a dilemma for both the employer and the job seeker.

In an attempt to solve both the challenges that go with low unemployment and the roadblocks for those convicted to find employment, the Wisconsin Policy Forum looked at how more people could get past misdeeds sealed from public view. Their work resulted in a new report released Wednesday, June 6.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

According to the report, it’s estimated more than a million people have convictions that may prevent them from getting a job in Wisconsin.

Michael Mills and Joshua Ellison (left to right) as they wait outside a free legal clinic on expungement held at the Urban League of Greater Madison June 2. Shamane Mills/WPR

Joshua Ellison is one of them. He says he’s been hired and fired before he even started a job because employers did a background check. So he takes any job he can get, like at a local rendering plant.

“The last 10 years I have been working in areas that don’t look into your background,” Ellison said. “My last job was at Bailey Farm in Marshall and they don’t do background checks there.”

He’s been able to get work — on and off — but has been shut out when it comes to housing.

“They won’t really let you in with a felony,” he said. “It’s a big inhibitor to growing and moving up in life.“

Recently, he and a friend were waiting outside the Urban League of Greater Madison where they hoped to meet with lawyers that could explain how certain offenses can be sealed from public view under what’s known as expungement.

“I came here because I have a felony on my record from 12 years ago, its been holding me back in job opportunities and other things in life,” Ellison said.

Ellison was convicted of felony bail jumping after being charged with felony fraud when he was 23 for writing a check on his former girlfriend’s account for money that he says she owed him. He later took the fraud charges to trial — which were dropped — but during the process of his hearings he had an encounter with the police and was charged with obstruction of justice for refusal to give his name to officers before knowing what he was being charged with. That run in resulted in both the obstruction of justice and the bail jumping charge.

But that occurred before 2009; so it cannot be taken off his record under Wisconsin law.

About 2,000 cases are expunged — or removed from public view — each year, according to the report by the Wisconsin Policy Forum. But it’s not easy. Expungement applies only to certain crimes. The offender has to be younger than 25, and the judge has to order expungement at sentencing. The report says no other state does this.

So those seeking a second chance at life have only one chance to ask that their record be sealed. A person can’t come back later and tell a judge they made mistakes while they were young, but are now a responsible adult.

People wait inside the Urban League of Greater Madison for their chance to talk to an attorney about getting past convictions sealed. Shamane Mills/WPR

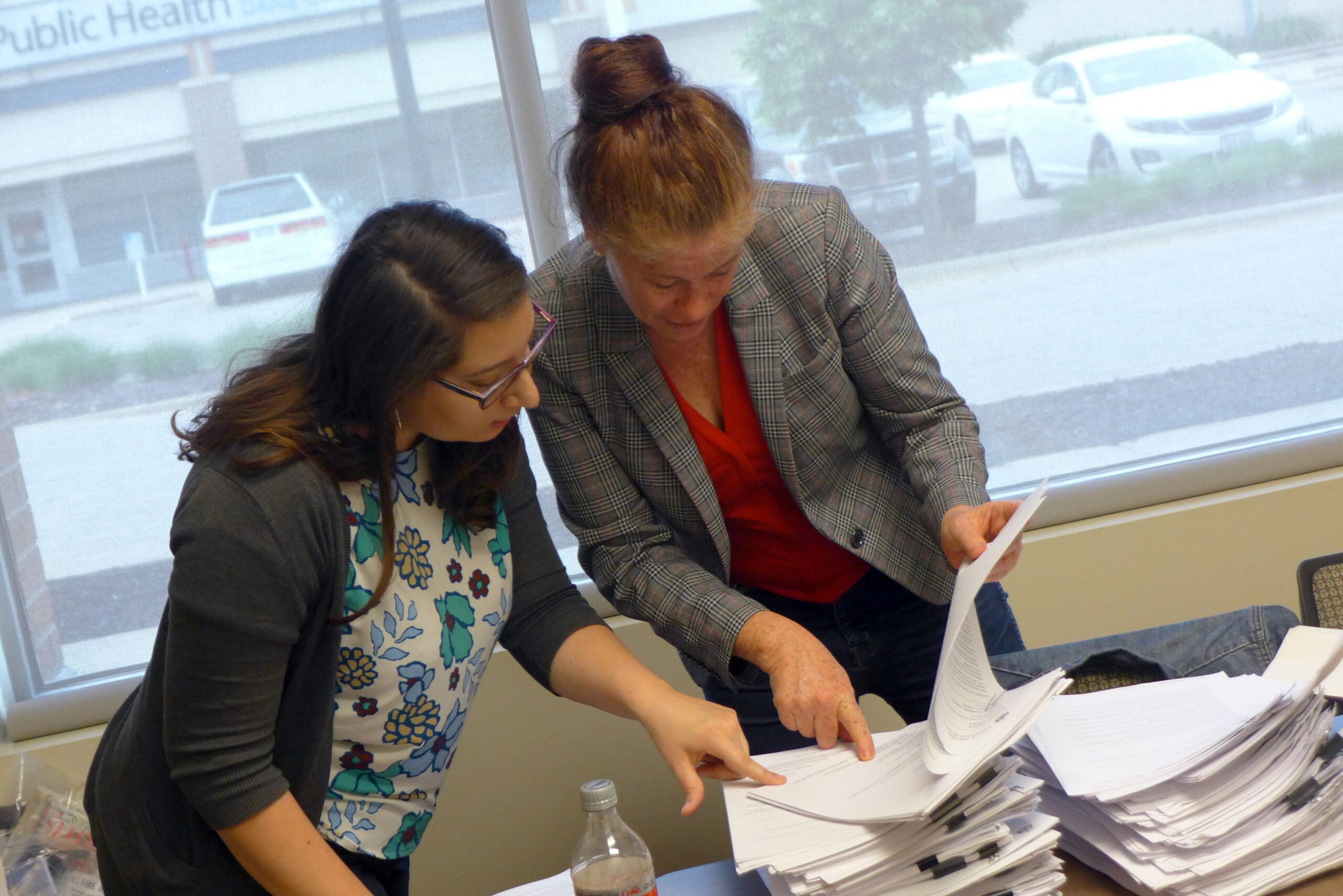

Sheila Sullivan is an attorney with Legal Action’s Road to Opportunity Project. Sullivan along with 16 other volunteer attorneys recently pored over criminal records at a free legal clinic at offering expungement advice. The free clinic, held at the Urban League of Greater Madison, was the same one Ellison and his friend attended.

“We have people who are looking for work who are now in their 30s who had four or five felonies when they were kids, they haven’t had anything in the last 10 or 15 years but they still have a felony record,” said Sullivan.

Based on the hurdles Wisconsin requires to qualify for expungement, the Wisconsin Policy Forum suggests that Wisconsin appears to have a stricter expungement law than all of its neighboring states except Iowa.

“We are probably a state that has made the fewest changes in our expungement law. In parts of the South many red states and purple states have moved in this direction. So we don’t do that. We also don’t have certificates of rehabilitation, we don’t do a lot of things what would basically remove the barriers,” Sullivan said.

During this legislative session, lawmakers tried but failed to agree on a bill that would have made expungement an option for more people. Among other things, it would have allowed offenders to apply for expungement after a case is closed.

That change could affect thousands.

The Wisconsin Public Policy report said going back to 2006, there have been more than 30,000 closed cases in Milwaukee County that could be expunged if the law changed. Ellison’s friend, Michael Mills, said people who serve their sentence deserve another shot at life.

“I think what people forget is that most people generally want to do the right thing. Dilemmas and circumstances determine how people think. Most people where I’m from before they know about their rights before they’ve lost them, they don’t even know about them,” Mills said. “A lot of times people forget that when you’re poor, survival for today outweighs a future,“ said Mills.

The report details some of the professional licenses not available to some or all ex-offenders. Registered nurse and paramedic licenses are out. Someone with a criminal record can’t become an architect or certified public accountant. They’re also not allowed to drive a school bus or cut hair as a barber.

When Sullivan consults clients about expungement she sometimes offers career advice as well, using a job at a pharmacy as an example.

“If you’ve got two convictions for possession with intent to deliver it might not be a good idea to invest $100,000 in education to become a pharmacy technician,” she said.

That’s because employers can refuse to hire someone convicted of a crime that pertains to their job, in this case dispensing medication.

“So a lot of time people make choices about careers, when they’re trying to get their life on track by borrowing money, going into training programs and they need to be thinking about what’s in their record and how it’s going to affect that choice going forward,” she said.

Expungement clinics have been held in Milwaukee and Madison. The most recent one at the Urban League of Greater Madison was well attended. Attorneys were concerned they’d have to turn some in the crowd away. But as the report notes, many ex-offenders don’t know about expungement and the opportunities it could bring.

Correction: An earlier version of this story cited out-of-date unemployment figures. It has been updated.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.