Over the last 19 years, mining for metallic minerals like copper and gold in Wisconsin has been effectively banned by state law. But an effort to clear the way for sulfide mining is picking up steam and reopening decades old fault lines between environmentalists and the mining industry.

In early January, state Sen. Tom Tiffany, R-Hazelhurst, fired a shot across the bow of the state’s environmental groups. He announced plans to repeal a 19-year-old law that has kept sulfide mining out of Wisconsin.

In August, Tiffany introduced his bill titled the Mining for America Act.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

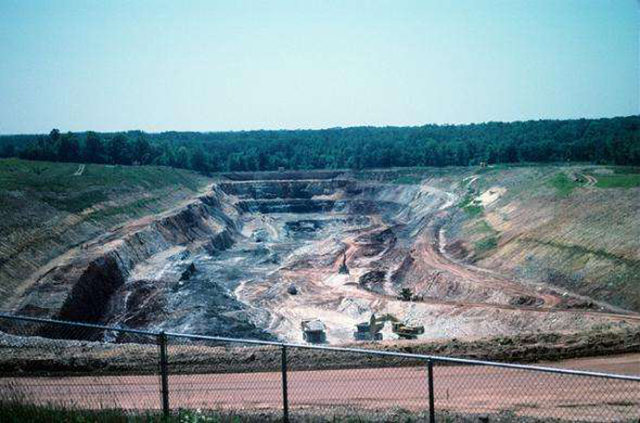

Aerial view of the old Flambeau Mine. Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

“I don’t believe there should be a moratorium on legal processes,” Tiffany said in August. “You know, mining is a legal activity and we should be able to permit it, regulate it and that’s what our bill will do.”

Sulfide mining is one of the ways we get metals such as copper, gold, silver and zinc. Tons of rock loaded with the metallic minerals are crushed and processed to extract the valuable metals. But that rock is also loaded with other minerals called sulfides, and when exposed to air and water they can leach acid into nearby streams and groundwater.

The 80-acre Flambeau Mine, located 1 mile south of Ladysmith along the Flambeau River in northwestern Wisconsin, was the only sulfide mine to operate in the state under modern regulations. The Flambeau Mining Co., a subsidiary of international mining firm Rio Tinto, employed 70 people and produced 180,000 tons of copper along with millions of ounces of silver and gold.

The mine generated $10 million in revenue for local governments while it was mining and shipping ore from 1993 to 1997, Ladysmith City Administrator Al Christianson said.

“The original plan here was to mine for five years because copper prices were quite high. During the course of the mine, it was decided to expedite it; and it was, in fact, pretty well mined out to a depth of about 225 feet in a period of four and a quarter year.” Christianson said.

A scenic overlook at the shore of the Flambeau River marks the spot where treated water discharged from the Flambeau Mining Co. operation near Ladysmith. Rich Kremer/WPR

Fear of acid mine drainage was so strong in the late 1990s that after another, larger operation was proposed by Exxon Mobil Corp. near Crandon — located east of Rhinelander and just outside the Chequamegon-Nicolet National Forest — a large majority of state legislators from both parties passed the mining moratorium law in 1998.

The moratorium requires a company to give examples of sulfide mining operations in North America that operated or were closed for 10 years without polluting before they can mine in Wisconsin. In a 1997 interview with Wisconsin Public Television, bill author former Rep. Spencer Black, D-Madison, said the moratorium was about putting the brakes on an over eager industry.

“Those minerals have been there hundreds of millions of years,” Black said. “They’re going to be there a few years more, and we should make sure that we don’t put our environment and our economy at risk just because Exxon thinks it would be more profitable to move this forward quickly.”

In the debate over Tiffany’s bill to repeal the sulfide mining moratorium, the Flambeau Mine is now used as an example by supporters and opponents alike.

Depending on who you ask, it was either a safe mine or a legacy polluter.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources lists a small, intermittent stream on the property as an impaired waterway because of unsafe levels of copper and zinc, but lists the source as unknown.

In 2011, environmental groups filed a lawsuit against the Flambeau Mining Co. over the pollution. In a mixed 2012 ruling federal Judge Barbara Crabb said the mine violated federal clean water laws but that the company’s environmental practices were exemplary.

Crabb’s decision was overturned by an appeals court.

Tiffany claims the Flambeau Mine is an example of how sulfide mining can be done safely, even claiming it would qualify as an example of a clean closure under the current moratorium law and bring a billion dollar industry to a part of the state that sorely needs it.

“I believe that we can do this appropriately,” Tiffany said. “I believe the Flambeau Mine in Ladysmith is a perfect example of how we can mine for nonferrous minerals safely.”

This rolling prairie near Ladysmith was once the site of the 80-acre Flambeau Mine. The mine is being used as an example by supporters and opponents of bill to repeal a 19-year-old sulfide mining moratorium. Rich Kremer/WPR

But even though the property was restored into a prairie in 1998, the company still hasn’t applied for its final certificate of completion with the state DNR.

When asked whether it plans to seek final DNR approval, Dave Cline, general manager of Health, Safety and Environment at Rio Tinto and president of Flambeau Mining Co., said Rio Tinto hasn’t decided.

“We have not proceeded yet,” Cline wrote in a statement. “As we learned with the previous successful certificate of completion process for the majority of the site, it’s a very time consuming and costly process for us as the petitioner. At some point, we may proceed but we have not yet made that decision.”

Tiffany’s bill to make it easier for companies to mine in Wisconsin sulfide deposits has reawakened some of the environmental groups that fought to pass the moratorium law in 1998.

The night before the bill’s public hearing in September in Ladysmith, opponents gathered in the basement of the Rusk County Community Library, which was paid for by a donation and taxes from the mining company. Among the speakers was Al Gedicks, a retired sociology professor and executive secretary for the Wisconsin Resources Protection Council.

Gedicks claimed the mining moratorium law wasn’t blocking the mining industry from operating in Wisconsin at all.

“All the moratorium is saying is … show us what you say is true,” Gedicks said. “The mining industry has consistently said for the past 20 years that they can do mining safely in a sulfide ore body and all the moratorium is saying is, ‘OK, fine, show us.’ So, we’re not imposing something on the mining industry that they haven’t already suggested is possible and doable.”

Fewer than 100 people attended the public hearing in September. Rich Kremer/WPR.

Tiffany’s public hearing was held in the Ladysmith High School auditorium. Just outside the entrance of the auditorium Tiffany’s staff parked a Toyota Prius with a sign listing all the metals contained in it.

During the testimony, a parade of pro-mining speakers talked about great untapped mineral resources. Mining consultant Roger David Morton said there are belts of rock called greenstone containing metals like copper, zinc, gold and silver.

“There is a tremendous potential for the future for developing these greenstone belts in Wisconsin into something that will really contribute what you need, namely employment and cash flow,” Morton said.

George Meyer, who served as DNR secretary when the moratorium was enacted, testified at the hearing as well. He has long been an opponent of the law and has claimed it doesn’t do anything to help regulators ensure safe mining in Wisconsin.

Meyer said that when Exxon Mobile came to the DNR for a permit to mine in Crandon, it provided three examples of what it claimed were clean sulfide mine closures.

“One of the mines was in the desert of Arizona. Remember, we’re regulating the Crandon Mine, in a water rich area, the headwaters of the Wolf River,” Meyer said. “The second was in Nunavut (in Canada) in permafrost. The third was in the foothills of the mountains in California. None of them provided any valuable information on how we should mine in Forest County Wisconsin. But our staff did get to see some beautiful places.”

Meyer said instead of the “prove it first” provision, mining law should require prospective mines to provide examples of the latest technology they would use to mitigate pollution in Wisconsin before they are permitted.

Tiffany’s bill to repeal Wisconsin’s sulfide mining moratorium has yet to be scheduled for a vote. He said he hopes to pass it before the end of the year.

Industrial buildings left behind from the Flambeau copper mine near Ladysmith are now used by the state Department of Natural Resources and a local utility company. Rich Kremer/WPR

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.