Teachers in the Lake Mills School District want to see more safety precautions against the coronavirus and ultimately a switch to all-virtual learning because of the current COVID-19 surge statewide.

More than 20 educators filed safety grievances with the district, a process that escalates their concern through the district hierarchy. Safety grievances have become a more common tool for teachers, who are banned from striking by law, to force district officials to respond to their COVID-19 concerns.

“It’s fear for myself, but fear for my coworkers and also fear for my students, and their families in the community,” said Brenda Morris, an English teacher and school librarian at the high school who filed one of the grievances.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Morris, a union leader, said she couldn’t remember anyone filing a grievance over safety concerns in her 22 years at the district, but noted teachers also haven’t faced the kind of direct health and safety threat posed by the coronavirus before.

“I’ve put a lot into this district, and I really care about the kids I work with,” she said, “but if I had any choice, I don’t think I would’ve gone back (to school) — this situation is just unprecedented.”

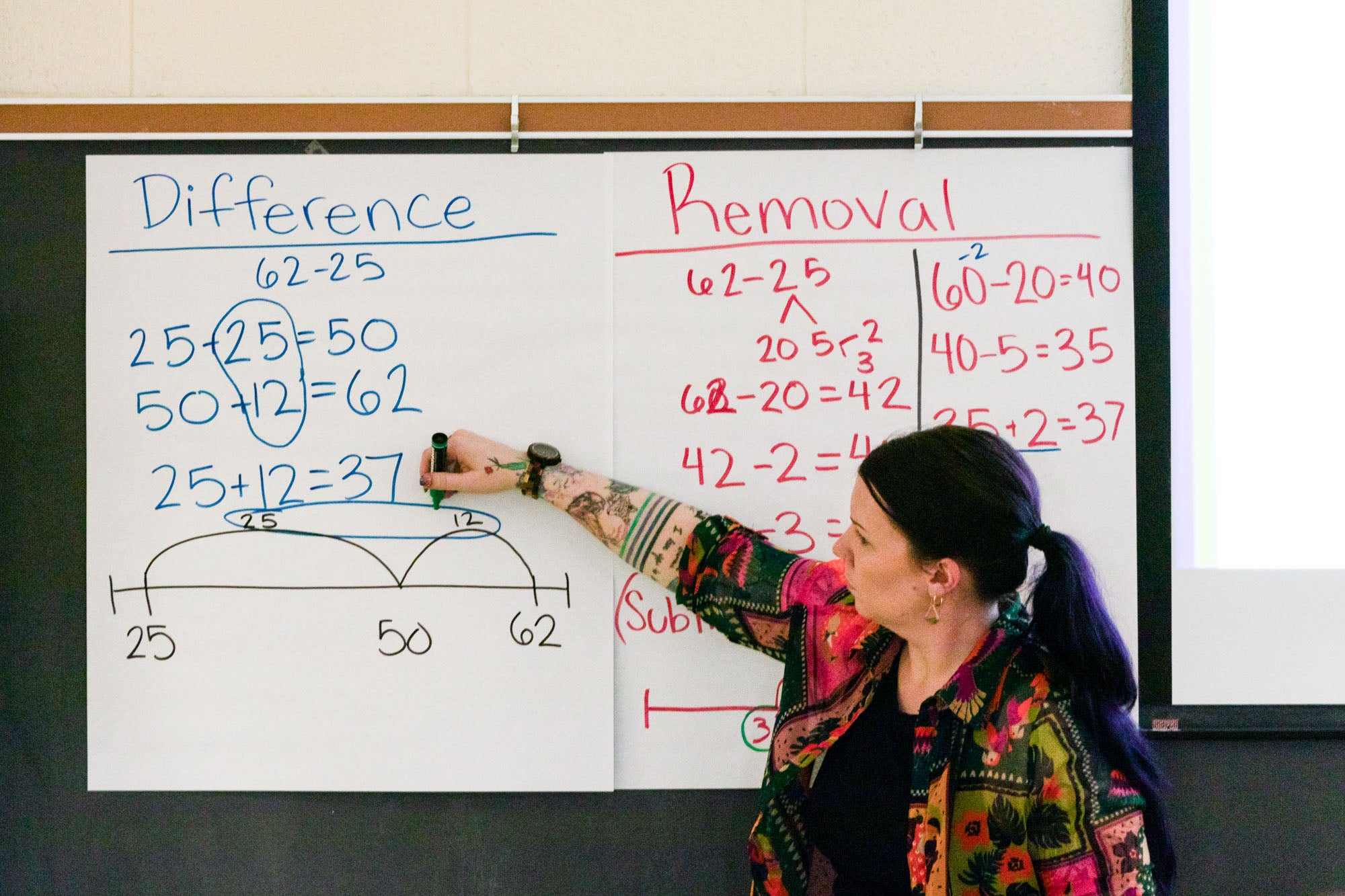

Beth Denzin, who teaches remedial and Advanced Placement math at the district, said after the school’s reopening plan came out in July, she spent the next three weeks making face masks because she was concerned about teachers’ exposure.

“I pulled out my sewing machine and my stash, and I just made tons and tons of face masks,” she said.

A few things struck her as concerning the moment she saw the district’s reopening plan this summer, which prioritized all in-person learning. The first was the district was going to try to keep high school classes to 25 students to allow for better distancing.

Denzin said the district tries to cap class sizes at 28 in a typical school year, but still ends up with classes with up to 32 students, so she wasn’t confident the district could bring that down to an even lower threshold.

Other issues became more apparent after classes started, she said. The high school has been using a safe cleaning solution to spray all the desks between classes, but it needs to sit on the desktops undisturbed for 10 minutes to work.

“We only have six-minute passing periods,” she said. “You have to have kids get up a few minutes early, or have them wait — and often my AP classes go bell-to-bell.”

Denzin, Morris and the other teachers who filed grievances want those kinds of concerns addressed, but they said what they’re looking for above all is a clearer policy on what would trigger a school closure — and one in line with recommendations from the state, county and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The teachers say the district had initially set those kinds of goalposts, but remained open as the county surpassed its initial virtual trigger point of per-capita positive cases, and even as the county health department recommended closure.

District administrator Tonya Olson said those guidelines have adapted as schools around the country have learned more about how the disease spreads among children, and as it’s responded to parents’ needs.

Olson said the district updated its pandemic plan a couple of months ago as more information has become available.

“We decided to go with an approach where we looked at several factors, and not just one measure from a COVID dashboard,” she said. “We did decide to look at what was actually happening within our own specific community, and not just looking at county-wide or statewide.”

Olson said she took her local contact tracing course, and has been working with the school nurse to map out how any students, staff or other school personnel who tested positive contracted the disease.

“That’s kind of my number one driver. Right now, it’s been a lot of the parents have tested positive, so the child has tested positive,” she said.

If, suddenly, she started seeing cases that were spreading within the school, Olson said she’d be more likely to move classes to virtual only.

In the meantime, though, she noted parents overwhelmingly favor in-person learning, and an in-person learning environment is better for kids’ mental health, learning outcomes and social ties.

“Besides just delivering academics, schools provide so much more as far as social-emotional counseling. We’ve got a lot of students that receive special education support,” she said.

Olson said about 80 percent of students opted for in-person instruction, even though the district has a virtual option that parents could choose. She said several families even switched to in-person instruction at the start of the quarter after starting virtually.

That point isn’t one the teachers dispute. Both Morris and Denzin talked about the difficult trade-offs for kids, especially in terms of their mental health and feelings of social isolation, in an all-virtual setting. They also understand caregivers working out of the home — as many Lake Mills families do — rely on schools for child care during the day.

“I know these families are having pressure to have their kids in school so that they can work, but I also feel there’s a fundamental unfairness in a system that says we can’t support people while we keep them safe,” Morris said.

She also acknowledged the limitations of a grievance, which push schools and districts to respond, but don’t affect higher-level policy. Morris said she’s more frustrated that families and school districts were even put in the position of making these kinds of calls in the face of a global pandemic.

“What’s our Legislature doing, and why does this burden fall on schools?” she said.

For Denzin, the formal grievance process was a way to force a response from local officials, after weeks of raising her safety concerns to no avail.

“I have sent so many letters and so many emails to our board, to my superintendent, to the county, to my state representative, to my national representatives,” she said. “I didn’t feel like we were being heard or any of our concerns were being addressed, and through a formal grievance process, they actually have to address our concerns.”

Under the grievance process, those formal complaints go first to the teachers’ direct supervisors, then to their school principals. Since the principals are their direct supervisors, the Lake Mills teachers combined those first two steps, and some have already progressed to the third step, landing on Olson’s desk. Next, they’ll go to an impartial hearing officer, and finally to the school board.

Teachers in Lake Mills initially tried to take their grievances directly to the board, since it has direct power over whether to move schools to a fully virtual option, but the grievances were dismissed by the board and had to be sent back up through the five-step process.

Even if the school district switches to all-virtual learning, which Olson said may be necessary if COVID-19 spread is worsened by the holidays, as many fear, Denzin and Morris said they plan to continue to push their grievances through the process to force clearer guidelines.

“We’re not just asking for a shift to virtual, we’re asking also for those clear parameters based on safety,” said Morris.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.