Rising rent, stagnant wages and a lack of available units have left Milwaukeeans navigating an affordable housing crisis. This crisis, say local housing experts, is a legacy of the city’s past policy choices.

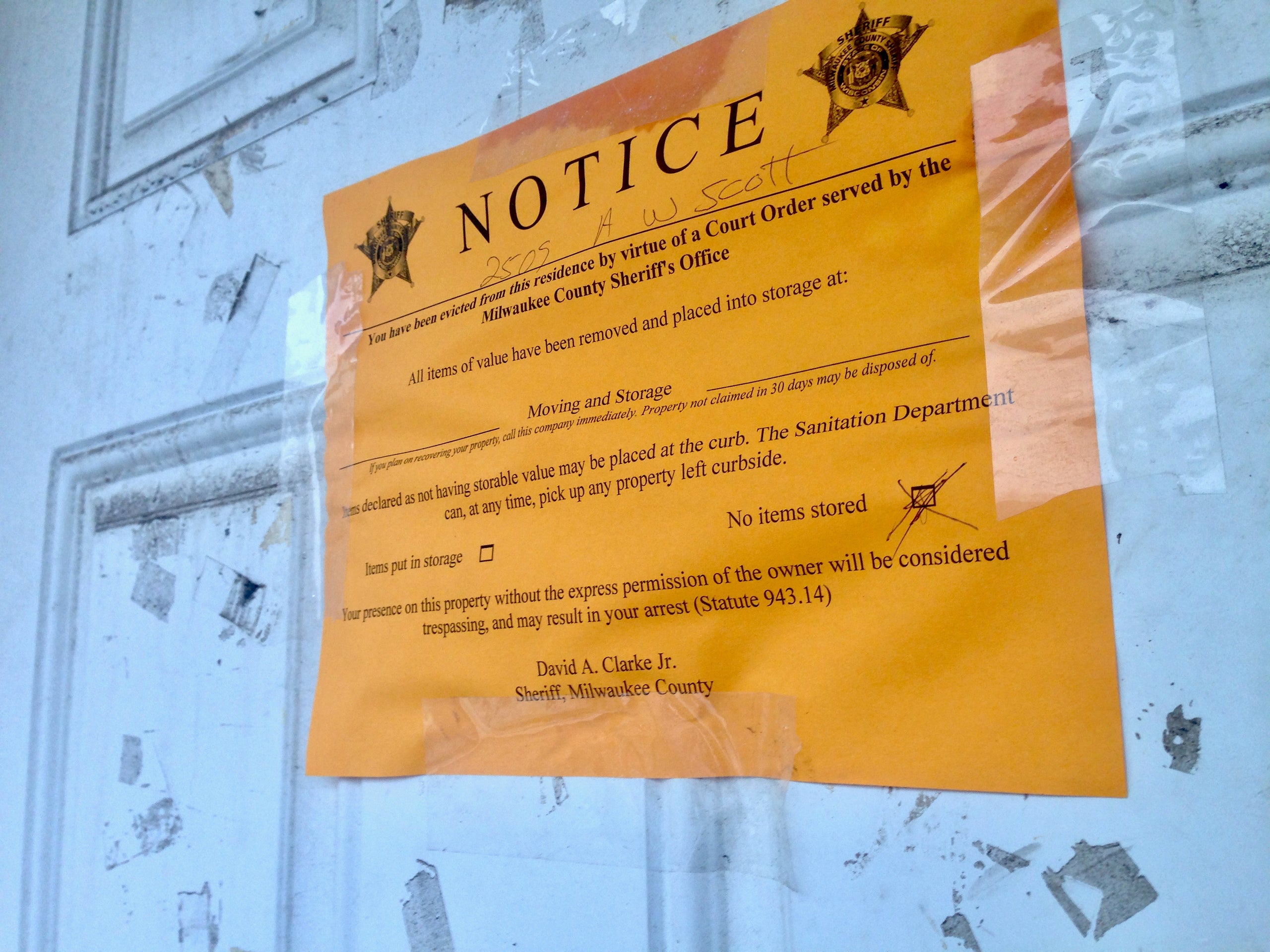

Although Milwaukee County was recently recognized for counting the nation’s lowest total of unsheltered people per-capita, it has also been center stage for its homeownership gap, its burdensome level of evictions and its housing shortage.

The combination has left many Milwaukeeans without options.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

This was avoidable.

Anne Bonds, a geography professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, said we are seeing the result of redlining, the discriminatory process of denying services to residents based on race or ethnicity, and racial covenants play out in real time.

“People like to chalk up the city’s segregation to people living where they are comfortable and other socioeconomic reasons,” Bonds said. “But the reality is neighborhoods are this way by design.”

She said racially restrictive practices and policies channeled investments to the suburbs, where even now, wage-sustaining job growth continues to occur outside the city, leading to “a concentration of disadvantage and overall disinvestment in urban communities.”

“Over time, the ideas of what neighborhoods are good, and which are bad have reinforced themselves,” she said. “Journalist Jane Jacobs referred to what has happened as a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

‘Households in crisis’

These dynamics play out in brutal fashion even today.

“There are just a lot of households in crisis,” said Deb Heffner, the housing strategy director for Community Advocates, which provides services and assistance to residents in need. “Rental assistance is just a Band-Aid fix for the actual issues.”

The organization has provided rental assistance funds to more than 15,000 people since 2020 and had around 4,000 people waiting for assistance as of mid-May.

Mike Bare, the research and program coordinator for Community Advocates, said housing and health are linked.

“You can draw a straight line from housing issues to suicides,” Bare said. “So what people might see as an individual housing problem becomes a public health issue and that becomes all of our problems.”

A recent Community Advocates Public Policy Institute report said housing issues can lead to chronic stress, and that chronic stress can have severe health consequences.

“Constant, chronic exposure to elevated levels of these hormones can harm health in many ways,” the report said. This includes chronically elevated blood pressure, which contributes to stroke and heart disease; chronically high blood sugar, which can lead to obesity and diabetes; and chronic immune system suppression, leaving people more vulnerable to infection, cancer, and autoimmune disease.

A history of housing problems

Experts say past policies have shaped the state of affordable housing now.

“Though they can’t be enforced, some of those (restrictive) covenants are still in the books,” said Bethany Sanchez, the director of the Fair Lending Program at the Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council. “This is the legacy of our past choices.”

It has been a disruptive legacy.

“There was a point when Milwaukee had the strongest Black middle class in the country,” said U.S. Rep. Gwen Moore, D-Milwaukee. “Now it’s deemed the worst place in the country for Black children to grow up.”

Moore pointed to disappearing jobs, a lack of transportation to available jobs that pay living wages and predatory lenders as other reasons for the crisis.

“You can point to rising rent but it’s a lot less than rent in New York or California,” she said. “We have to look at what’s unique to this community.”

Bare said these things have happened in other places, but they just happened here earlier, and Milwaukee has yet to recover.

“Macroeconomic factors like deindustrialization hit Milwaukee 10 to 20 years before it hit other cities,’ he said. “That means we had an earlier failure of the housing market and loss of equity in families.”

In addition, the city has new housing barriers. Bonds pointed to unfair renting practices.

“Rent is extremely high in low-income areas,” she said. “And other research shows private equity firms who are allowed to buy a bunch of property and tend to evict tenants at much higher rates than local and even out-of-state individual landlords.”

Bare and Heffner said the lack of available units is also hampering recovery.

A report by the Community Development Alliance, a group of community development funders and practitioners that collaborate on neighborhood improvement efforts in Milwaukee, identified the need for 32,000 additional Black and Latino homeowners and 32,000 rental units for families making $7.25 to $15 per hour.

The report from 2019 said in the city of Milwaukee, 55.8 percent of white people are homeowners, while 37.5 percent of Latinos are homeowners, and only 27 percent of people who are Black are homeowners.

Milwaukeeans have been making efforts to address the issue for years.

In 2018, the City of Milwaukee launched its 10,000 Homes Initiative to improve affordable housing opportunities for 10,000 households in the city in 10 years.

A report by the Wisconsin Policy Forum said there are more than 70 organizations in the city serving people’s housing needs.

“While housing is the primary focus for some of those organizations, it is one of the multiple areas of focus for most,” the report noted. “Most responding organizations reported having partnered with at least one public sector organization within the last three years to provide housing services and/or to develop affordable housing.”

Organizations have been offering solutions to address these issues.

The Community Development Alliance identified a series of solutions in its 2021 report outlining an affordable housing plan for the city. These included post-purchase homeownership counseling and an acquisition fund to build affordable rental homes.

A 2020 Public Policy Institute report suggested a series of policy changes in its report on the health of renters. These included policies to preserve existing affordable housing and to expand tax-incremental financing for affordable housing developments.

The Wisconsin Policy Forum report also suggested solutions to housing challenges such as developing more affordable and mixed-income housing near employment centers.

“We just want to put the information in front of people,” said Joe Peterangelo, the senior researcher for the Wisconsin Policy Forum. “Hopefully, it informs and influences a conversation.”

Where to find housing help in Milwaukee

The Metropolitan Milwaukee Fair Housing Council is working on providing access to more low-income families in the city.

And the Rental Housing Resource Center, which streamlines a series of housing services and service providers into one space and process, is open every day at 728 N. James Lovell St. to help people navigate their immediate housing needs. You can call them at (414) 895-RENT (7368).

Legal Action of Wisconsin is working to reduce how long evictions are on someone’s record.

Resources to consult if you’re worried about eviction:

Community Advocates rent helpline: 414-270-4646

Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee: 414-727-5300

Mediate Milwaukee: 414-939-8800

Legal Action of Wisconsin: 414-278-7722

Social Development Commission: 414-906-2700

Milwaukee Autonomous Tenants Union: 414-410-9714

Eviction Free MKE: 414-892-7368