The idyllic American family conjures up images of a home in 1950s suburbia, a white picket fence, a golden retriever and 2.5 kids.

The United States’ total fertility rate indicates that, for the U.S. to sustain its current population, women need to have an average of 2.1 children.

If that birthrate isn’t sustained, the country risks a shrinking workforce, economic decline and a dwindling tax base.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Those risks have turned into reality.

The United States’ total fertility rate is now 1.7 kids and falling. Almost half of non-parent adults tell the Pew Research Center they will likely not have any children.

Northeastern Wisconsin families understand why. They know the persistent struggle to afford everything from diapers to housing. It now costs $310,600 to raise a child from birth to age 18, a 9.1 perent increase from five years ago, according to The Brookings Institution, a Washington, D.C. nonprofit public policy organization.

One challenge has become particularly severe: Child care.

The Economic Policy Institute found that a year of infant care can cost Wisconsinites more than tuition at a public college. Families have started to plan pregnancies around the availability of care, as they encounter years-long wait lists at child care centers.

Missy Schmeling, executive director at Encompass Early Education and Care Inc., hears about families’ struggles when they visit one of Encompass’ seven Brown County locations in search of a slot.

“We have families asking where the food pantries are, about transportation,” Schmeling said. “It’s an impossible burden on families. And another child will require more care.”

The NEW (Northeast Wisconsin) News Lab is launching its fourth series, “Families Matter,” covering issues important to families in the region. This year, reporters from six news outlets — Green Bay Press-Gazette, Appleton Post-Crescent, Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Watch, The Press Times and FoxValley365 — will spotlight the daily struggles families face, dig up solutions and options, and explain why these topics impact not only families, but the whole state.

A ‘really tricky spot’: Child care imperative for many Wisconsinites

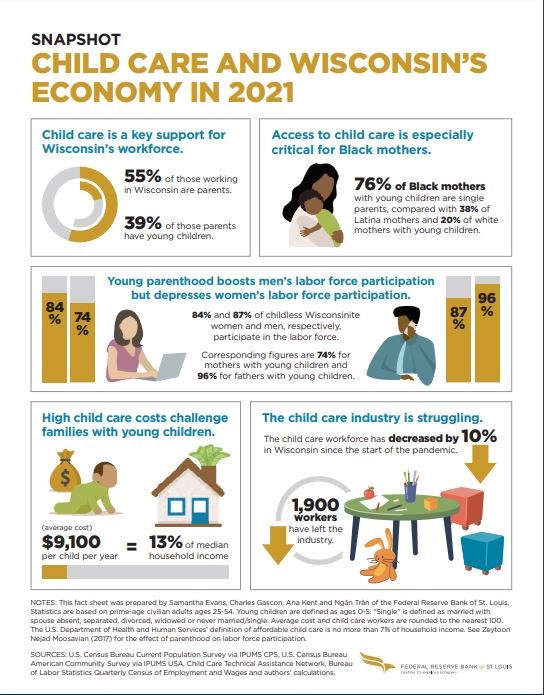

In more than 70 percent of Wisconsin households with children under 6, all available parents are in the workforce, according to Annie E. Casey Foundation data.

Without access to affordable child care, parents are forced to work less, ultimately earn less and risk deeper financial struggle.

“There’s this really tricky spot that I feel like a lot of millennials have found themselves in where you are making too much money for it to make sense for one of you to stay home, but not enough money to feel comfortable with how much money you have to put toward daycare,” said Christine Gunderson, a Green Bay mom whose infant is in full-time child care.

Child care issues may result in a parent moving from full-time work to part-time. A parent may have to sacrifice their career and earnings altogether. Others may find no feasible solution.

Plus, not just any care is acceptable.

Experts say 85 to 90 percent of a child’s core brain development occurs before the age of 5, and quality child care teaches social emotional skills that are key for school readiness. High-quality early education is even linked to higher career earnings later in life, according to Alejandra Ros Pilarz, an early care and education researcher.

‘It’s kind of wild it’s come to that’: Parents time pregnancies around child care

Tammy Dannhoff opened Kids Are Us Family Child Care in her Oshkosh home 34 years ago. Seeing families were timing pregnancies around child care providers’ openings, she added a “Baby Watch” section to her newsletter, to keep parents in the loop regarding openings.

As of early 2023, her center’s next opening was in fall 2026.

Given the state of child care availability in Wisconsin, planning far in advance doesn’t seem so far-fetched. The Center for American Progress in 2018 estimated more than one in two Wisconsinites lived in a child care desert — an area where care is not available or the number of children exceeds the number of slots. Rural areas are worse: 70 percent of rural Wisconsin is a child care desert. Staffing shortages regularly exacerbate availability issues. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Brown County lost an estimated 600 child care slots to closures and providers opting to retire, according to Family and Childcare Resources of Wisconsin officials.

Lack of available care leads to massive waitlists. For example, Encompass had about 350 children on its waitlist in January. Some centers do not know when the next opening might be.

Even if families get on waitlists as soon as they learn they’re pregnant, Wisconsin parents still might not be able to secure a slot at their first-choice facility. Some might still be without care by the time their child is born.

A friend told Green Bay’s Destiny Desotell to get on child care waitlists after she learned she was pregnant in May 2021. By that summer, she was on several wait lists and shocked when some centers told her it’d be years before they had an opening for an infant.

“Essentially, you have to be like, ‘I think I am going to have a kid in two years, put me down on the waitlist now,’ because it’s a realistic expectation that it’s going to be a two-year wait,” Desotell said.

Eventually, Desotell secured care for her infant, now 13 months old, at Encompass’ Bellin Health Center location in Allouez. Her child received priority placement because she works for Bellin as a cardiac sonographer. Even then, the spot was not open until a month after Desotell returned from maternity leave, forcing her to bridge the gap with a licensed, in-home provider and help from her family.

Abby Funseth of New Glarus timed the conception of her second child, who is now 7 months old, around a child care opening. To even consider having another child, she said she needed to know she had care lined up first.

The Funseths were given a two-month window if they wanted their second child to make it into an opening at Corrine’s Little Explorers. They met that timetable, but that might not be possible for every family.

“The entire … trajectory of our family planning came down to child care and its lack of availability,” Funseth said. “You put pressure on this timeframe to conceive a child, and it just takes all of the joy out of it. It’s like a business (transaction).”

Alex Steen, a Beaver Dam mom, is thinking about child care as she plans to have a second child. She recently paid Community Care Preschool & Child Care Inc., which her 2-year-old daughter attends, $200 to secure an infant spot.

“It’s kind of wild that it’s come to that: that you can place your unconceived children on a waitlist just to ensure they have care when they come about,” she said.

Unaffordable care also contributes to larger age gaps between children

“Affordable” child care is defined as costing no more than 7 percent of a family’s household income, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“That’s not a realistic number to attain,” Schmeling said.

In reality, a typical Wisconsin family with an infant and a 4-year-old spends 33.6 percent of its income on child care, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Infants typically require more costly care.

Brown, Outagamie, Winnebago and Fond du Lac county families are familiar with these costs. Home-based child care for one infant will cost a median-income family 10.5 to 12.2 percent of their income, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. Center-based care costs 14.7 to 17.4 percent of the median household income.

Meanwhile, a minimum wage worker in Wisconsin would spend on average 83 percent of their income on child care, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Tyler Sjostrom of Appleton said child care for he and his wife’s two children costs more than their mortgage, car payments, insurance and utilities combined.

“I don’t know anybody who has kids in day care who isn’t always a little bit seething about (the cost),” Sjostrom said. “If you get a group of parents together and somebody mentions day care, it descends into chaos really quick.”

Costs may be high — Northeast Wisconsin families pay an average of $11,000 to $13,000 per year for in-center toddler care — but what families pay often does not cover all of a center’s operating costs, such as rent, maintenance and food, or allow it to provide its employees with a living wage and competitive benefits.

Green Bay’s Savannah Zoch and her husband feel high-quality early education and care is vital to early childhood development. Because Zoch is a community engagement specialist for Encompass, she receives a 60 percent employee discount on child care for her two children — a lifesaver for her family.

“Without the Encompass employee discount, I would basically be working to pay for child care,” Zoch said.

Because of the high cost of child care, many families now wait to have a second child until their first begins school, at least part time. That’s the case for Steen, who said she’ll probably wait until her daughter enrolls in 4K.

Currently, her daughter only attends child care three days a week, but if it were five days a week, the cost would make having a second child impossible, she said.

“In our situation, we are settling for a larger age gap than we might truly want,” Steen said.

Anna Schneider, a mom of two from Denmark and sister to Abby Funseth, wants a third child, but financial concerns are also prompting her to wait.

“You want to be able to have kids when you want to have kids, but financially speaking, it doesn’t make any sense for us to have three kids in day care right now because it would make more sense for one of us to stay home (and not work),” she said.

To delay or not to delay? That is the dilemma.

Waiting to have a second or third child, however, may come with its own costs.

Gunderson pointed out that car seats expire and may need to be replaced, and other equipment, like cribs, may be deemed unusable due to recent safety upgrades.

While children are in care, parents often have to make sacrifices. Sjostrom said child care costs determine his family’s discretionary income. For other families, the tradeoffs may be more grave. Roughly one in three households in Brown, Outagamie, Winnebago and Fond du Lac counties are already below the federal poverty level or struggle to afford the basic cost of living, according to the 2020 Wisconsin ALICE Report.

Age is also a consideration for many parents — both the age gap between their children and their own.

Desotell is in her late 20s, and her husband is in his early 30s.

“(My 13-month-old) still sometimes doesn’t sleep through the night consistently, and I don’t know if I want to do that at 35,” Desotell said.

It’s a reality more families will have to confront, as many parents are starting families later in life.

U.S. Census American Community Survey data shows that between 2011 and 2021, fewer people between the ages of 20 and 34 bore children, while the birth rate among ages 35 to 50 steadily increased.

Medical professionals generally categorize giving birth at 35 or older as “advanced maternal age.” While it is increasingly common for people to have children after 35 — even a first child — the medical community recognizes there are medical risks to both the pregnant person and baby.

That’s something that has been on Funseth’s mind recently.

“When we think about the potential of adding another child to our family, I’m thinking about: ‘When does my oldest go into the school system so we won’t be paying for her day care anymore?’” she said. “And … ‘When will (our child care provider) have another opening for a baby?’ That might be for a couple of years yet, and I’m almost 35; will we be able to have another?”

Beyond families: the broader impact of the child care crisis

Northeast Wisconsin’s child care crisis is taking an increasing economic toll, too. As such, employers and economic development organizations are already realizing its impact their workforce.

It’s no secret that Wisconsin’s workforce situation is less than ideal: “Help wanted” signs adorn most workplaces, and in September Forward Analytics projected the state could lose 130,000 working-age people by 2030.

The report said women drove a decline in workforce participation among all Wisconsinites ages 35 to 44 and cited family reasons, including a lack or high cost of child care, as potential contributors to the trend.

Child care challenges have a ripple effect, costing Wisconsin’s economy $1.1 billion annually, Raising Wisconsin, the advocacy arm of Wisconsin Early Childhood Association, found. The same study found 75 percent of business owners believe child care affects the economy, and 86 percent of caregivers said child care issues hurt their work time.

Christina Thor, Wisconsin director for the advocacy group 9 to 5 – National Association of Working Women, said available, affordable child care — like affordable housing and adequate health care — can either attract people to Wisconsin or hasten young peoples’ departures.

“We are estimated to lose 130,000 residents by 2030,” Thor said. “That’s young people moving from the state for different opportunities. That’s huge. And that’s scary.”

Ana Hernández Kent, a senior researcher at the Federal Reserve’s Institute for Economic Equity, said employers miss out on potential employees when they do not consider the needs of working moms. While 84 percent of women without children are employed, that figure falls to 74 percent for working mothers.

“If you talk about women in the economy, you can’t do that without talking about child care issues. (Women and mothers) bear the brunt of taking care of the kids whether or not they work,” Kent said. “But it also has broader implications. If a mom has to take time off she didn’t want to, it impacts their (family’s) financial stability, their economic mobility.”

Because women bear a disproportionate brunt of child care responsibilities, flexible workplace policies like the ability to work from home, child care assistance and paid family leave have already become vital benefits to working parents.

“Those kinds of things are really positive for women and mothers,” Kent said.

Northeast Wisconsin workforce would ‘boom’ if child care issues were resolved

Thor prefers to think about what Northeastern Wisconsin would look like if the region found ways to address families’ child care needs, especially the “big, big gap” in culturally-competent child care she said the region’s increasingly diverse communities need.

“We’d bloom,” Thor said. “I feel like our workforce would boom.”

Raising Wisconsin estimates addressing child care needs would enable 250,000 people to enter the state’s workforce.

Ann Franz, executive director of the Northeast Wisconsin Manufacturing Alliance, said manufacturers recognize the need to do something different. Wisconsin Aluminum Foundry now offers employees a $400 monthly reimbursement to help with child care costs while Schreiber Foods is testing a $5,000 annual child care stipend for workers at two of its facilities. A variety of employers secured Partner Up Grants from the state to provide child care for their employees.

“There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, but there are a lot of resources that can help our companies and our region know the options,” Franz said.

Shawn Phetteplace, Midwest regional manager for Main Street Alliance, a group that empowers small businesses to create policy changes, warns that leaving the issue to businesses alone could lead to further inequity for small businesses.

“If child care becomes a benefit that an employer provides rather than a broad-based community asset, it puts small businesses at a competitive disadvantage,” Phetteplace said. “If we make public investments in health care, child care, paid leave, (small businesses) can increase pay. It creates a level playing field for them to grow.” “

Wisconsin stands to reap huge economic benefits if family-friendly incentives allowed more women and minority residents to enter the workforce, studies such as Council for a Strong America’s “Want to Strengthen Wisconsin’s Economy? Fix the Childcare Crisis” have shown.

Just like many other issues families face, the child care crisis cannot be solved with a single program, grant, innovation, incentive or change.

But such solutions are what Sjostrom, the Appleton father of two, longs for.

“I hope that we’re still not talking about this when my kids have kids, but I also think that if we are, (my wife and I) will understand and try to help,” Sjostrom said. “There has to be a solution where families aren’t mortgaging everything for the right to have kids and help them thrive.”

Contact Jeff Bollier at 920-431-8387 or jbollier@gannett.com. Follow him on Twitter at @JeffBollier.

Madison Lammert covers child care and early education across Wisconsin as a Report for America corps member based at The Appleton Post-Crescent. To contact her, email mlammert@gannett.com or call 920-993-7108. Please consider supporting journalism that informs our democracy with a tax-deductible gift to Report for America.

What would help make family life better in Northeast Wisconsin? This is one of the questions the NEW News Lab hopes to answer in 2023. Write to the lab at families@wisconsinwatch.org or call 608-262-3642 and leave a message with your name, what you’re calling about and phone number.